0176

Non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging agent for in-vivo nitric oxide activity detection1Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Translational Biology & Engineering Program, Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3The Edwards S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Inflammation, Preclinical

We report a novel nitric oxide (NO)-sensitive MRI contrast agent that holds potential for detecting endogenous NO. Type I collagen and HEK cell lysate showed strong binding with NO agent, while HSA and various ROS/RNS species showed NO agent was only activated by NO. In vivo washout rate was also tested, and NO agent cleared from mice 7 days after intraperitoneal injection. Prolonged enhancement was observed in the heart after isoproterenol injection, which indicated excess NO production and inflammation. The NO agent shows promise as a molecular imaging agent in early detection of inflammatory diseases.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a free radical molecule involved in the vascular, neuronal, and immune systems. NO synthesis is catalyzed by nitric oxide synthases (NOS) in-vivo and among the NOS group, the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is primarily associated with innate immune responses. The expression of iNOS can be activated in different immune cells during inflammatory responses, and the NO generated is involved in phagocytosis of pathogens1. Due to its signalling role in various pathological processes, the detection and quantification of NO continues to be an active research area. However, noninvasive in vivo detection of NO remains a challenge. Problems encountered in previous attempts include shallow imaging depths, low resolution, and the need to inject NO probe locally at inflammation site2,3. Herein, we report the in-vitro validation of a NO-activated manganese bifunctional chelating agent and its application to detect endogenous NO in an isoproterenol-induced murine heart failure model.Methods

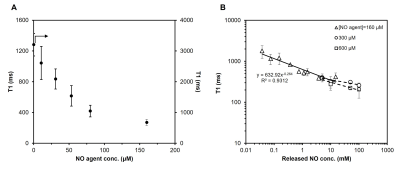

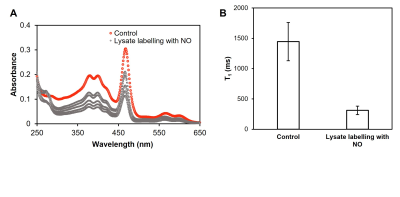

To validate the protein-binding ability of NO agent in the presence of NO, the agent was incubated with a NO donor and type I collagen gel. Three NO agent concentration was used (160 μM, 300 μM, 600 μM), and the released NO concentration ranged from 30 μM to 100 mM. Labelled collagen gels were sonicated at 37°C to remove non-covalently bound NO agent before being scanned on a 3T preclinical scanner (MR Solutions, Guildford, UK).We also tested the binding capability of our NO agent when placed in a mixture of proteins. Cell lysate was produced from human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. The same incubation protocol with NO agent was applied. Ultra centrifugal filter was used to remove any unreacted NO agent. MRI and UV-Vis spectrometry (Beckman Coulter, Brea, Calif) were done to verify binding.

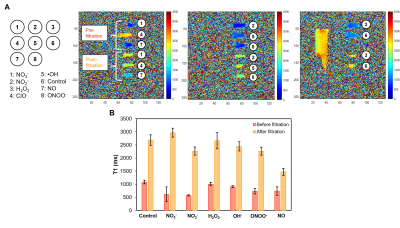

Selectivity of NO agent against different reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) was evaluated using human serum albumin with 1 mM of various ROS/RNS producing reagents. All solutions were purified by ultra centrifugal filters. The amount of NO agent retained in solution was quantified using UV-Vis spectrometer and MRI.

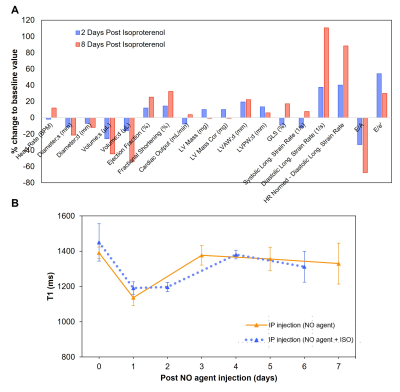

In-vivo distribution of NO agent after subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection in male BALB/c mice was studied longitudinally up to 7 days post injection on MRI. To test the feasibility of detecting in vivo NO, we used the ß-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol hydrochloride to cause acute cardiomyocyte necrosis and trigger an immune response against the heart4. A single high dose of isoproterenol was given followed by NO agent injection 3 days later. T1 map of the heart was acquired longitudinally to monitor changes in T1 value of the left ventricular wall. Respiratory gating with a T1-weighted FLASH sequence with the following parameters were used: TE=min; TR=7 ms; FA=[2°, 5°, 10°, 15°, 20°]; FOV=50 mm; reconstruction with Retro85.

Results and Discussion

T1 reductions caused by NO agent at different concentrations are shown in Figure 1A; the minimum T1 was observed at ~160 μM. Binding with collagen (Figure 1B) and T1 enhancement caused by excess NO agent at high NO concentrations were similar. Binding of NO agent in HEK cell lysate showed significant retention of NO agent in the presence of NO (Figure 2). In NO agent selectivity test, only the sample incubated with NO showed significantly reduced T1, showing its exclusive activation by nitric oxide (Figure 3). In-vivo kinetic study showed faster washout rate of NO agent via the intraperitoneal route than subcutaneous route in kidneys and liver (Figure 4A), and bladder and aorta (Figure 4B). Cardiac function assessed by echocardiography prior to and following isoproterenol injection showed left ventricular dysfunction, including inotropic and chronotropic effects (Figure 5A). Subsequent T1 maps acquired after NO agent injection exhibited prolonged contrast enhancement in the heart (for 3 days) compared to the control mice. Further optimization, such as increasing dosage to the clinically approved 0.1 mmol/kg, will be made to augment the contrast observed when inflammation is present.Conclusion

We have developed a novel NO-sensitive MRI probe for detection of early inflammation. In-vitro experiments demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity of detection, and in-vivo MRI in a mouse model of acute heart failure showed prolonged T1 enhancement in the heart after injury.Declaration of Conflicts

A provisional patent has been filed on this invention: “Manganese bifunctional chelating agent conjugation platform for targeted MR imaging”. (GB2216233.3, filed 2022-11-01).Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

(1) Epstein, F. H.; Moncada, S.; Higgs, A. The L-Arginine-Nitric Oxide Pathway. N Engl J Med 1993, 329 (27), 2002–2012. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199312303292706.

(2) Reinhardt, C. J.; Zhou, E. Y.; Jorgensen, M. D.; Partipilo, G.; Chan, J. A Ratiometric Acoustogenic Probe for in Vivo Imaging of Endogenous Nitric Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (3), 1011–1018. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b10783.

(3) Chen, X.-X.; Wu, Y.; Ge, X.; Lei, L.; Niu, L.-Y.; Yang, Q.-Z.; Zheng, L. In Vivo Imaging of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction by Simultaneous Monitoring of Cardiac Nitric Oxide and Glutathione Using a Three-Channel Fluorescent Probe. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2022, 214, 114510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2022.114510.

(4) Forte, E.; Panahi, M.; Baxan, N.; Ng, F. S.; Boyle, J. J.; Branca, J.; Bedard, O.; Hasham, M. G.; Benson, L.; Harding, S. E.; Rosenthal, N.; Sattler, S. Type 2 MI Induced by a Single High Dose of Isoproterenol in C57BL/6J Mice Triggers a Persistent Adaptive Immune Response against the Heart. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25 (1), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.15937.

(5) Daal, M. R. R.; Strijkers, G. J.; Calcagno, C.; Garipov, R. R.; Wüst, R. C. I.; Hautemann, D.; Coolen, B. F. Quantification of Mouse Heart Left Ventricular Function, Myocardial Strain, and Hemodynamic Forces by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JoVE 2021, No. 171, e62595. https://doi.org/10.3791/62595.

Figures

Selectivity test of NO agent against ROS and RNS using HSA. (A) Radical species tested with NO agent and T1 maps of each sample before and after filtration for unbound NO agent. (B) T1 changes of each sample showing NO donor treated HSA sample has the lowest T1 after purification.

Longitudinal imaging of NO agent treated male BALB/c mice. (A) T1 changes of the kidneys and liver after subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection. (B) T1 changes of the bladder and aorta after subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection.

Assessment of left ventricular dysfunction after isoproterenol injection in male BALB/c mice. (A) Cardiac function assessment by echocardiography prior to and following ISO injection. (B) Longitudinal imaging before and after NO agent injection for monitoring T1 changes of the myocardium.