0172

Anisotropic stiffness of ex vivo swine heart estimated by transversely isotropic nonlinear inversion MRE at 2mm isotropic voxel resolution1Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Center for Biomedical Imaging (CIBM), Lausanne, Switzerland, 3Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 4Thayer school of engineering, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, United States, 5McKelvey School of Engineering, Washington University, Saint Louis, MO, United States, 6Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, United States, 7Biomedical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 8Mechanical Engineering, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Elastography

MR elastography (MRE) must account for the anisotropic nature of myocardial tissue to accurately quantify stiffness. The constitutive matrix for this material was rotated to align with the fibers. One ex vivo swine heart was scanned with DTI and MRE sequences at 2 isotropic voxel resolution. Transversely isotropic viscoelastic stiffness was reconstructed using the Non-Linear Inversion (NLI) algorithm. Elastic properties (shear and Young’s modulus, tensile and shear anisotropy) were segment dependent, in agreement with the myocyte sheetlet formation, which varies in size and spacing according to the myocardial segment. Similarities between MRE and DTI metrics could be observed.Introduction

MR elastography (MRE) can quantify stiffness in various cardiac pathologies1-3. However, to date, these approaches have not considered the anisotropic nature of the myoarchitecture, which is known to introduce variance in MRE results up to 30%4. High resolution studies of the cardiac microstructure by X-ray phase contrast5-7 showed that myocyte orientation and sheetlet size are segment dependent. Moreover, the collagen matrix of the myocardial wall forms a honeycomb arrangement8, constituting a deformable material of high tensile strength in order to maintain its structure8. The matrix assists in the lengthening of myocytes during diastole and prevents myocytes from over-stretching9,10. This collagen honeycomb is a "shape-memory" material that re-structures itself according to myocyte orientation 9, and forms laminar "sheetlets" which are separated by cleavage planes. The sheetlets thickness and their branching patterns vary transmurally to accommodate for sheetlet motion11. These myocyte angulations and sheetlet differences define the different biomechanical roles for each myocardial segment12. Better differentiation of the segmental variation of anisotropic stiffness could help to improve the characterization of this complex myocardial structure and understand the biomechanics of myocardial pathologies.Methods

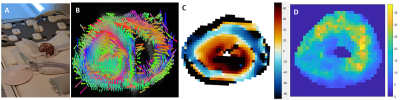

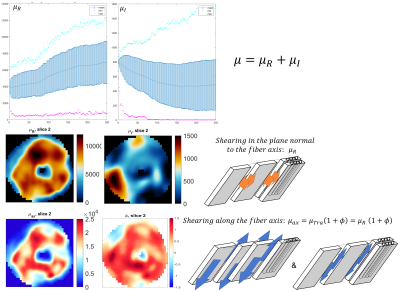

One freshly excised ex vivo porcine heart was scanned on a 3T MRI (Figure1-A). MRE data were collected using a Resoundant MRE actuator at 100Hz and encoding gradient amplitude at 40mT/m in a spin echo EPI sequence with parameters13: FOV=340 mm2; TR/TE=540/109 ms; BW=1730 Hz, 3 slices and 2 mm3 isotropic voxel; FOV=200 mm2; TR/TE=2300/132 ms; BW=962 Hz, 10 slices and 1 mm3 voxel; DTI data with resolution and FOV matched to the MRE scans were also acquired with 32 diffusion-encoding gradients at b=557 s/mm² (3 averages); TR/TE=1500/70ms. The angulation of the myocytes was calculated by projecting the first eigenvector (Figure1-B) onto the circumferential plane (Figure1-C). Anisotropic mechanical properties of the heart were treated by the NLI-MRE subzone post-processing method formulated with a finite element based, nearly incompressible, transverse isotropic material model14-17, where the axis of symmetry is rotated based on DTI data to align with the primary fiber axis. The constitutive equation for this material is given by:$$$ \left(\begin{matrix}{\sigma^\prime}_{11}\\{\sigma^\prime}_{22}\\{\sigma^\prime}_{33}\\{\sigma^\prime}_{12}\\{\sigma^\prime}_{23}\\{\sigma^\prime}_{13}\\\end{matrix} \right)=\left[\begin{matrix}c_{11}&c_{12}&c_{13}&0&0&0\\c_{21}&c_{22}&c_{23}&0&0&0\\c_{31}&c_{32}&c_{33}&0&0&0\\0&0&0&c_{44}&0&0\\0&0&0&0&c_{55}&0\\0&0&0&0&0&c_{66}\\\end{matrix}\right] \left(\begin{matrix}{\epsilon^\prime}_{11}\\{\epsilon^\prime}_{22}\\{\epsilon^\prime}_{33}\\{2\epsilon^\prime}_{12}\\{2\epsilon^\prime}_{23}\\{2\epsilon^\prime}_{13}\\\end{matrix}\right) $$$,(1)

with the components of the 6x6 elasticity matrix, [C], given by, (2):

$$$\begin{matrix}c_{11}=\ \kappa+\frac{4}{3}\mu\left(1+\frac{4}{3}\zeta\right),&c_{22}=c_{33}=\ \kappa+\frac{4}{3}\mu\left(1+\frac{1}{3}\zeta\right),\end{matrix}$$$

$$$\begin{matrix}c_{44}=c_{66}=\mu\left(1+\phi\right),\end{matrix} \begin{matrix}c_{12}=c_{13}=c_{21}=c_{31}=\ \kappa-\frac{2}{3}\mu\left(1+\frac{4}{3}\zeta\right),\end{matrix}$$$

$$$\begin{matrix}c_{32}=c_{23}=\ \kappa-\frac{2}{3}\mu\left(1-\frac{2}{3}\zeta\right),&c_{55}=\mu\end{matrix}$$$

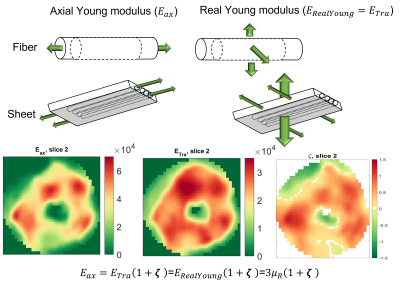

where μ is the shear modulus in the plane normal to the fiber axis, Φ is the shear anisotropy, ζ is the tensile anisotropy, and κ is the isotropic bulk modulus. From (2), it can be seen that the two axial shear moduli, $$${\mu_{ax}}$$$ corresponding to shearing in the along the fiber axis, are given by $$${c_{44}}$$$ and $$${c_{66}}$$$ while the transverse shear modulus, $$${\mu_{tr}}$$$, corresponding to shearing around the fiber axis (no fiber influence), is given by $$${c_{55}}$$$. Hence, $$${Φ=\frac{μ_{ax}}{μ_{tr}}-1}$$$ and $$${ζ=\frac{E_{ax}}{E_{tr}}-1}$$$, with E the Young’s modulus. Suitability of the MRE displacement data for the non-linear inversion was assessed using the Octahedral Shear Strain Signal to Noise Ratio18 (Figure1-D). To verify plausible dependency between structural organization and stiffness, the transverse angle and the transverse shear modulus were measured across the myocardial wall.

Results

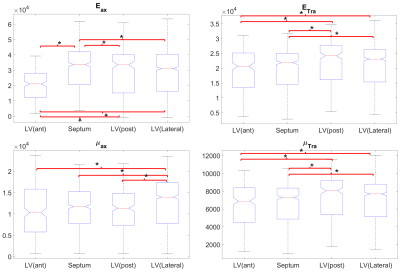

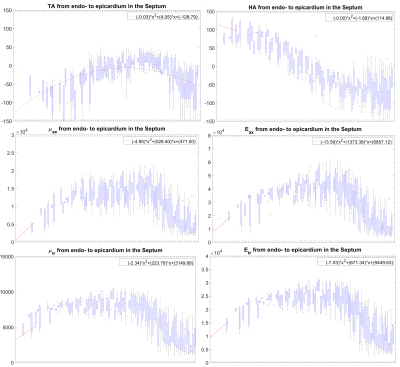

In the LV, tensile anisotropy was $$${\zeta_{ax}=0.32±0.43}$$$, shear anisotropy was $$${\phi_{ax}=0.66±0.40}$$$, and shear modulus was $$${\mu_{tr}=6.9±2.15}$$$ KPa (Figure 2) which compares with previous studies considering isotropic tissue (3.84±0.4 KPa at end‐diastolic and 4.94±0.5 KPa at end‐systole)2. Sheetlets are 1.66 times more resistant to shear in the fiber planes compared to shearing through their plane ($$${\mu_{ax} versus \mu_{tr}}$$$). The axial Young’s modulus of the fiber was $$${E_{ax}=28.8±14.8}$$$ KPa (Figure3), or 2.43 stiffer than axial sheetlet shearing ($$${\mu_{ax}}$$$) and 1.32 times stiffer than Young’s modulus normal to the fiber axis ($$${E_{tr}}$$$). Segment wise, the axial Young’s modulus of the septum ($$${E_{ax}=31.8±14.3}$$$ KPa, Figure4) was significantly higher than the other segments while the lateral wall had the highest shear modulus along the fiber axis (resistance of sliding sheetlets, $$${\mu_{ax}=11.4±4.99}$$$ KPa). Sliding sheets experience more resistances ($$${\mu_{ax}}$$$, $$${\mu_{tr}}$$$) when they are parallel to the circumferential plane (Figure5).Discussion

Stiffness values using MRE in the human LV was reported at 4.99±1.05KPa19, 20, based on isotropic models, while our anisotropic model shows much more stiffness, 7-8KPa. Fibers were ~1.3 times higher in axial tensile stiffness than transverse, which is in line with tension tests20. The septum has the highest sigmoidal gradient, mainly longitudinal fibers across the wall, with a quasi-absence of sheetlets from the mid-wall to the epicardium6, and correspondingly show more tensile anisotropy ($$${E_{ax}}$$$, resistance along the fiber) than shear anisotropy ($$${\mu_{ax}}$$$, resistance of the sliding sheetlets). The lateral and posterior walls have thick sheetlets, large cleavage planes, and a linear angulation of the myocytes6, corresponding to high $$${\mu_{ax}}$$$ and lower $$${E_{ax}}$$$. The transverse angle and shear modulus show reasonable agreement. In fact, these transverse patterns mean that the fiber field has a radial component adding a mechanical coupling between the posterior and anterior layers, therefore changing the distribution of shearing. However, our model cannot account for intersecting sheet orientations, which disagrees with the presence of orthogonal sheetlets6. The ability to differentiate stiffness across segments will help to better detect pathology and understand biomechanics.Conclusion

Stiffness of myofibers and sheetlets can be differentiated in an ex vivo animal model. These stiffnesses vary across myocardial segments and are dependent on the microstructure organization.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Mazumder R, Schroeder S, Mo X, et al.: In vivo magnetic resonance elastography to estimate left ventricular stiffness in a myocardial infarction induced porcine model. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 45:1024–1033.

2. Mazumder R, Schroeder S, Clymer BD, White RD, Kolipaka A: Quantification of myocardial stiffness in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction porcine model using magnetic resonance elastography. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2016; 18:P29

3. Arani A, Arunachalam SP, Chang ICY, et al.: Cardiac MR elastography for quantitative assessment of elevated myocardial stiffness in cardiac amyloidosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 46:1361–1367.

4. Anderson AT, Van Houten EEW, McGarry MDJ, et al.: Observation of direction-dependent mechanical properties in the human brain with multi-excitation MR elastography. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2016; 59:538–546.

5. Varray F, Mirea I, Langer M, Peyrin F, Fanton L, Magnin IE: Extraction of the 3D local orientation of myocytes in human cardiac tissue using X-ray phase-contrast micro-tomography and multi-scale analysis. Med Image Anal 2017; 38:117–132.

6. Mirea I: Analysis of the 3D microstructure of the human cardiac tissue using Xray phase contrast microtomography. 2017.

7. Mirea I, Wang L, Varray F, Zhu Y-M, Davila Serrano EE, Magnin IE: Statistical analysis of transmural laminar microarchitecture of the human left ventricle. In 2016 IEEE 13th Int Conf Signal Process. IEEE; 2016:53–56.

8. Caulfield JB, Borg TK: The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest 1979; 40:364–72.

9. Hanley PJ, Young AA, LeGrice IJ, Edgar SG, Loiselle DS: 5-Dimensional configuration of perimysial collagen fibres in rat cardiac muscle at resting and extended sarcomere lengths. J Physiol 1999; 517:831–837.

10. Rohmer D, Sitek A, Gullberg GT: Reconstruction and Visualization of Fiber and Sheet. Lawrence Berkeley Natl Lab Publ 2006:LBNL-60277.

11. LeGrice IJ, Smaill BH, Chai LZ, Edgar SG, Gavin JB, Hunter PJ: Laminar structure of the heart: ventricular myocyte arrangement and connective tissue architecture in the dog. Am J Physiol 1995; 269(2 Pt 2):H571-82.

12. Colombo NM: Numerical modelling of ventricular mechanics : role of the myofibre architecture. 2014.

13. Johnson CL, Sutton B: Echo-planar imaging magnetic resonance elastography pulse sequence. 2016.

14. McGarry MDJ, Van Houten E, Guertler C, et al.: A heterogenous, time harmonic, nearly incompressible transverse isotropic finite element brain simulation platform for MR elastography. Phys Med Biol 2020.

15. Van Houten EEW, Paulsen KD, Miga MI, Kennedy FE, Weaver JB: An overlapping subzone technique for MR-based elastic property reconstruction. Magn Reson Med 1999; 42:779–786.

16. Smith DR, Caban-Rivera DA, McGarry MDJ, et al.: Anisotropic mechanical properties in the healthy human brain estimated with multi-excitation transversely isotropic MR elastography. Brain Multiphysics 2022; 3:100051.

17. McGarry M, Van Houten E, Sowinski D, et al.: Mapping heterogenous anisotropic tissue mechanical properties with transverse isotropic nonlinear inversion MR elastography. Med Image Anal 2022; 78:102432.

18. McGarry MDJ, Van Houten EEW, Perriñez PR, Pattison AJ, Weaver JB, Paulsen KD: An octahedral shear strain-based measure of SNR for 3D MR elastography. Phys Med Biol 2011; 56:N153–N164.

19. Khan S, Fakhouri F, Majeed W, Kolipaka A: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance elastography: A review. NMR Biomed 2018; 31:e3853. 22. Villalobos Lizardi JC, Baranger J, Nguyen MB, et al.: A guide for assessment of myocardial stiffness in health and disease. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2022 11 2022; 1:8–22.

20. Sommer G, Schriefl AJ, Andrä M, et al.: Biomechanical properties and microstructure of human ventricular myocardium. Acta Biomater 2015; 24:172–192.

Figures