0159

SwinV2-MRI: Accelerated Multi-Coil MRI Reconstruction using Shifted Window Vision Transformers1Electrical and Computer Engineering, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, United States, 2Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Reconstruction

Vision transformers (ViT) are increasingly utilized in computer vision and have been shown to outperform CNNs in many tasks. In this work, we explore the use of Shifted Window (Swin) transformers for accelerated MRI reconstruction. Our proposed SwinV2-MRI architecture enables the use of multi-coil data and k-space consistency constraints with Swin transformers. Experimental results show that the proposed architecture outperforms CNNs even when trained on a limited dataset and without any pre-training.

Introduction

Sub-Nyquist undersampled MRI reconstruction enables accelerated acquisition, reducing the long scan times traditionally associated with MRI. Conventional methods for undersampled MRI reconstruction include Parallel Imaging (PI)1,2,3 and Compressed Sensing (CS)4,5 techniques. Recent Deep Learning (DL) based approaches, mostly relying on supervised fully Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have been shown to produce higher quality reconstructed images compared to CS with lower inference latency6,7,8,9. More recently, Vision Transformers (ViT)12 are being investigated for this task10.Transformer networks, originally proposed for machine translation11, have in recent years been restructured for computer vision tasks first in the form of ViT, and now as Shifted Window (Swin) Vision Transformers13. At their core, ViTs divide input images into linearized patches, and employ Multi-layer Perceptrons (MLP) with global attention through Multi-head Self Attention layers to extract image features. Swin Transformers compute self-attention within non-overlapping local windows to enable effective feature extraction from image data while maintaining linear computational complexity to image size. The updated SwinV214 replaces the pre-normalization in the original with post-normalization and utilizes a scaled-cosine attention in place of the original dot-product attention. To date, Swin Transformers have only been used for single channel magnitude image domain MRI reconstruction15. In this work, we propose the SwinV2-MRI architecture that enables the use of SwinV2 Transformers with complex multi-coil MRI data combined with k-space data consistency constraints.

Methods

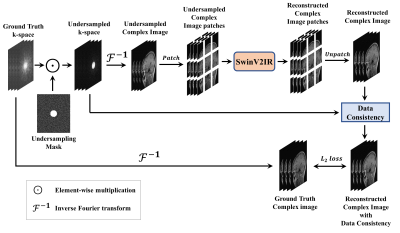

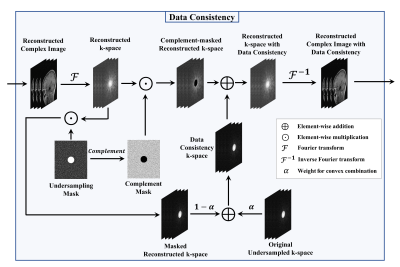

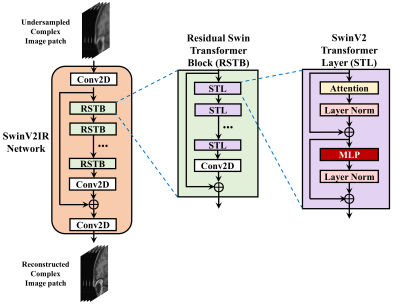

The proposed SwinV2-MRI Reconstruction pipeline is shown in Figure 1. During training, 2D slices of coil-compressed k-space data are first undersampled using a Boolean sampling pattern. The undersampled k-space slice is then converted to a complex image with the real and imaginary components stacked along the channel axis. Overlapping patches of this complex image are then sequentially reconstructed using a SwinV2IR network after which the patches are combined to recreate the full complex image. This output complex image is converted back to k-space and undergoes data consistency using data points from the original undersampled k-space, as shown in Figure 2. After data consistency, the resultant complex image is converted to a Root-Sum-of-Squares (RSS) coil-combined image for visual analysis and metric calculations.The SwinV2IR network is shown in Figure 3 and consists of SwinV214 Transformer layers arranged in a SwinIR16 cascade. The SwinV2IR structure consists of simple convolutional stages for high-level feature extraction at the beginning and at the end of the network, encapsulating a series of Residual Swin Transformer Blocks (RSTB), each of which, contains multiple Swin Transformer V2 layers. Inside the Swin layers, scaled-cosine attention and MLPs are utilized for deep feature extraction, interspersed with post layer normalization to prevent activation amplitude accumulation in deeper layers. As reference, a U-Net17 was also implemented and used in comparisons. The public Calgary Campinas brain MRI dataset18 was used for all experiments. The 67 fully-sampled 12-coil 3D T1-weighted k-space data volumes were randomly split into training-validation-test sets of 45-7-15 volumes respectively. Next, 150 2D sagittal complex k-space slices of dimensions 256×218×12 were extracted from the central region of each volume and then coil-compressed to 4 virtual coils using BART19. The data was saved as 256×218×8 arrays with the real and imaginary components stacked along the channel axis. A 5x undersampling of the k-space data was performed using a 2D Poisson sampling mask with a fully-sampled center to simulate accelerated acquisition. All DL methods used the same training data and no pre-training was performed for the Transformer network.

The U-Net used for comparison had four stages consisting of 64, 128, 256, and 512 convolution filters respectively. The SwinV2IR reconstruction network is comprised of 6 RSTBs each containing 6 SwinV2 layers with embed dimension length of 180. Each input image was divided into overlapping patches of dimensions 96×96×8 and the patches sequentially denoised using the reconstruction network. Adam optimizer was used for training with $$$L_2$$$ loss, initial learning rate of 2×10-4, and batch size of 2. The networks were trained for 100,000 iterations. The best models were used for testing. During training, k-space data consistency was gradually introduced over the first 10,000 iterations as explained in Figure 2. For testing, the original k-space was used for data consistency.

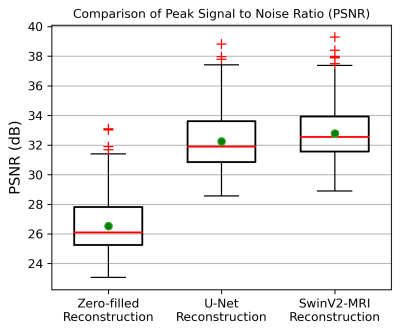

The trained networks were used to reconstruct undersampled test data (2247 slices) and PSNR was calculated using the RSS reconstructions of the predicted images and the ground truth data. A pairwise t-test was used for statistical comparison.

Results

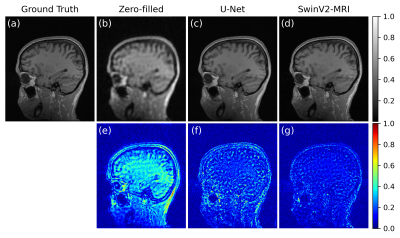

Figure 3 shows a comparison of the visual reconstruction quality of the DL networks on a sample test slice. The SwinV2-MRI reconstruction shows better recovery of details compared to the U-Net reconstruction. The difference images demonstrate the lower reconstruction errors obtained by the SwinV2-MRI.Figure 4 shows a quantitative comparison of PSNR over the full test set. The SwinV2-MRI approach produces higher average PSNR across the test data compared to U-Net ($$$p$$$ < 0.01 for pairwise t-test) with a tighter distribution.

Conclusions

We have shown that a Swin Transformer-based DL approach for undersampled MRI reconstruction can produce results superior to fully convolutional networks. Future optimization of the Transformer network and overall pipeline can potentially lead to further improved performance and better generalization over larger datasets due to the superior scalability of the Transformer architecture.Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge support from the Texas Instruments Foundation Endowed Graduate Scholarship Program at the University of Texas at El Paso and the Technology and Research Initiative Fund (TRIF) Improving Health Initiative at The University of Arizona.References

1. Pruessmann, K. P., Weiger, M., Scheidegger, M. B. & Boesiger, P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med 42, 952–962 (1999). PMID: 10542355.

2. Griswold, M. A., Jakob, P. M., Heidemann, R. M., Nittka, M., Jellus, V., Wang, J., Kiefer, B. & Haase, A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA). Magn Reson Med 47, 1202–10 (2002). doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. PMID: 12111967.

3. Uecker, M., Lai, P., Murphy, M. J., Virtue, P., Elad, M., Pauly, J. M., Vasanawala, S. S. & Lustig, M. ESPIRiT - An eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magn Reson Med 71, 990–1001 (2014). doi: 10.1002/mrm.24751. PMID: 23649942.

4. Lustig, M., Donoho, D. & Pauly, J. M. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med 58, 1182–1195 (2007). doi: 10.1002/mrm.21391. PMID: 17969013.

5. Lustig, M., Donoho, D. L., Santos, J. M. & Pauly, J. M. Compressed Sensing MRI. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 72–82 (2008).

6. Hyun, C. M., Kim, H. P., Lee, S. M., Lee, S. & Seo, J. K. Deep learning for undersampled MRI reconstruction. Phys Med Biol 63, (2018). doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aac71a.

7. Sriram, A., Zbontar, J., Murrell, T., Defazio, A., Zitnick, C. L., Yakubova, N., Knoll, F. & Johnson, P. End-to-end variational networks for accelerated MRI reconstruction. in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 64–73 (Springer, 2020).

8. Souza, R., Ca, R. M., Lebel, R. M., Frayne, R. & Ca, R. A Hybrid, Dual Domain, Cascade of Convolutional Neural Networks for Magnetic Resonance Image Reconstruction. Proc Mach Learn Res 102, 437–446 (2019).

9. Rahman, T., Bilgin, A. & Cabrera, S. Asymmetric decoder design for efficient convolutional encoder-decoder architectures in medical image reconstruction. in Multimodal Biomedical Imaging XVII 11952, 7–14 (SPIE, 2022). doi: https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2610084.

10. Lin, K. & Heckel, R. Vision Transformers Enable Fast and Robust Accelerated MRI. in Medical Imaging with Deep Learning (2021).

11. Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł. & Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017-December, 5998–6008 (2017).

12. Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

13. Liu, Z., Lin, Y., Cao, Y., Hu, H., Wei, Y., Zhang, Z., Lin, S. & Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (2021). doi: 10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986.

14. Liu, Z., Hu, H., Lin, Y., et al. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolution. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 12009–12019 (2022).

15. Huang, J., Fang, Y., Wu, Y., Wu, H., Gao, Z., Li, Y., Ser, J. del, Xia, J. & Yang, G. Swin transformer for fast MRI. Neurocomputing 493, 281–304 (2022). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2022.04.051.

16. Liang, J., Cao, J., Sun, G., Zhang, K., van Gool, L. & Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2021-October, (2021). doi: 10.1109/ICCVW54120.2021.00210.

17. Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. in International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

18. Souza, R., Lucena, O., Garrafa, J., Gobbi, D., Saluzzi, M., Appenzeller, S., Rittner, L., Frayne, R. & Lotufo, R. An open, multi-vendor, multi-field-strength brain MR dataset and analysis of publicly available skull stripping methods agreement. Neuroimage 170, 482–494 (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.08.021. PMID: 28807870.

19. Uecker, M., Ong, F., Tamir, J. I., Bahri, D., Virtue, P., Cheng, J. Y., Zhang, T. & Lustig, M. Berkeley advanced reconstruction toolbox. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med 23, (2015).

Figures

Figure 1: Proposed SwinV2-MRI framework for multi-channel MRI reconstruction with k-space data consistency using SwinV2IR. Multi-channel undersampled k-space data is converted to a complex image and patch-wise reconstructed using a SwinV2IR denoiser. The output patches are reassembled into an image, which undergoes k-space data consistency (see Figure 2). During training, the multi-channel output image is compared with the ground truth image to calculate the training loss.

Figure 3: SwinV2IR, Residual Swin Transformer Block (RSTB), and SwinV2 Transformer Layer (STL). The SwinV2IR network consists of initial and final convolutional stages encapsulating a number of RSTBs. Each RSTB consists of several STLs followed by a convolutional layer and a residual skip connection. Finally, each STL consists of a scaled cosine attention layer and a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), each followed by a layer normalization stage and residual skip connection.

Figure 5: Boxplots showing PSNR comparison over 2247 slices of reconstructed test data obtained using the different methods. The red line denotes the median and the green circle denotes the mean of each distribution. The mean test PSNRs and standard deviations for the zero-filled, U-Net, and SwinV2-MRI reconstructions are 26.53 ± 1.709 dB, 32.25 ± 1.777 dB, and 32.79 ± 1.634 dB, respectively. A paired t-test showed statistical significance ($$$p$$$ < 0.01) between SwinV2-MRI and U-Net reconstruction PSNRs.