0158

A Personalized Federated Learning Approach for Multi-Contrast MRI Translation1Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 2National Magnetic Resonance Research Center (UMRAM), Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 3University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Neuroscience Program, Aysel Sabuncu Brain Research Center, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Synthesis

MRI contrast translation enables image imputation for missing sequences given acquired sequences in a multi-contrast protocol. Training of learning-based translation models requires access to large, diverse datasets that are challenging to aggregate centrally due to patient privacy risks. Federated learning (FL) is a promising solution that mitigates privacy concerns, but naive FL methods suffer from performance losses due to implicit and explicit data heterogeneities. Here, we introduce a novel FL-based personalized MRI translation method (pFLSynth) that effectively addresses implicit and explicit heterogeneity in multi-site datasets. FL experiments conducted on multi-contrast MRI datasets show the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Introduction

Multi-contrast MRI protocols are pivotal in comprehensive diagnostic assessments, but they necessitate prolonged exam times for growing number of contrasts. Economic and labor costs of multi-contrast protocols can thereby prohibit collection of certain contrasts or repeat runs of corrupted acquisitions during an exam1-4. MRI contrast translation is a promising solution that imputes missing pulse sequences under the guidance of acquired sequences in a protocol5-11.Training generalizable translation models requires access to diverse imaging data from multiple institutions12,13. Federated learning (FL) is a recent framework for collaborative training of multi-site models without sharing local data to mitigate patient privacy risks14-18. A multi-site model can significantly improve performance for sites with limited and/or uniform local training data12,15,18. However, previous FL-based translation methods suffer from performance losses due to heterogeneities in the MRI data distribution19,20.

Data heterogeneity can arise due to implicit or explicit factors regarding translation tasks. Implicit heterogeneity occurs due to native variations in sequence parameters and imaging hardware across sites12,15. Explicit heterogeneity occurs due to involvement of variability in source-target contrast configurations across subjects11,21. Here, we introduce a novel personalized FL method for MRI translation (pFLSynth) that effectively addresses both implicit and explicit heterogeneity in multi-site MRI data.

Methods

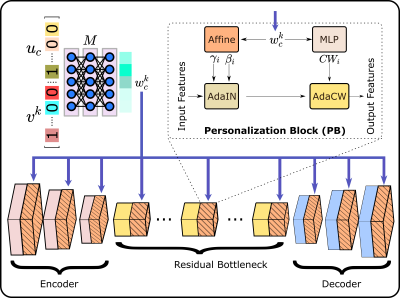

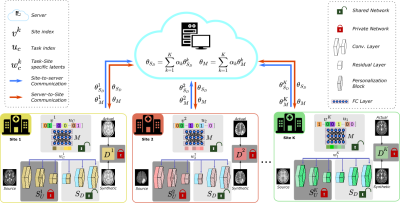

pFLSynth: For improved performance in multi-site studies, we introduce a personalized FL method for MRI contrast translation, pFLSynth (Fig. 1). pFLSynth leverages a generative adversarial model that receives a source image along with a site index to address implicit heterogeneity, and a source-target configuration index to adress explicit heterogeneity.Mapper: Receiving a binary vector for site index $$$v_k$$$ and a binary vector for indices of source and target contrasts $$$u_c$$$, $$$M$$$ produces a latent vector $$$w^k_c$$$ (Fig. 2).

Synthesizer: $$$S$$$ generates the target image, given as input a source image and latent vector $$$w^k_c$$$ (Fig. 2).

Personalization Blocks (PB): We introduce novel PBs inserted after each convolutional block in the synthesizer except for the final decoder block. At the $$$i$$$th layer, given $$$w^k_c$$$, PBs learn scale, bias vectors ($$$\gamma_i,\beta_i$$$), and relative channel weightings ($$$CW_i$$$) via trainable transformations. Afterwards, the statistics of feature maps are modulated via an AdaIN layer22, and channel weights are adapted via a novel AdaCW layer:

$$g^{'}_i=\mathrm{AdaIN}(g_{i},\gamma_i,\beta_i)=\begin{bmatrix}\gamma_i[1] \frac{g_{i}[1] - \mu(g_{i}[1])\mathbf{1}}{\sigma(g_{j}[1])}+\beta_i[1] \mathbf{1} \\ \gamma_i[2] \frac{g_{i}[2]-\mu(g_{i}[2])\mathbf{1}}{\sigma(g_{j}[2])}+\beta_i[2] \mathbf{1} \\ \vdots\end{bmatrix},f_{i}=\mathrm{AdaCW}(g^{'}_i,CW_{i})=\begin{bmatrix}g^{'}_{i}[1]\odot CW_{i}[1]\mathbf{1}\\ g^{'}_{i}[2]\odot CW_{i}[2]\mathbf{1} \\ \vdots\end{bmatrix} $$

where $$$g_{i},f_{i}$$$ are the input and output feature maps,$$$1$$$ is a matrix of ones,$$$\odot$$$ denotes Hadamard product, and $$$\mu(.),\sigma(.)$$$ compute the mean and standard deviation of individual channels.

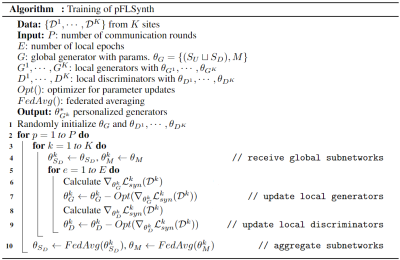

Federated Training: Fig. 3 outlines the training algorithm for pFLSynth based on partial network aggregation (PNA). The downstream synthesizer $$$S_D$$$ and mapper $$$M$$$ are shared across sites, albeit the upstream synthesizer $$$S_U$$$ and discriminator $$$D$$$ are unshared to improve site-specificity in image representations. In each round, local models are trained to minimize a compound local translation loss comprising adversarial and $$$\ell_1$$$ losses across tasks:

$$\mathcal{L}_{syn}^k=\sum_{c = 1}^{C}\mathbb{E}_{x^k_{s_c},x^k_{t_c}}[-(D^k(x^k_{t_c})-1)^{2}-D^k(\hat{x}^k_{t_c})^{2}+\lambda_{\ell_1}||x^k_{t_c}-\hat{x}^k_{t_c}||_{1}]$$

where $$$\hat{x}^k_{t_c}=G^{k*}(x^{k}_{s_c},v^k,u_c)$$$ is the translation estimate, $$$x^k_{s_c},x^k_{t_c}$$$ are the source and target contrasts for $$$c$$$th task configuration and $$$G^k,D^k$$$ are the generator and discriminator at site $$$k$$$, $$$C$$$ is the number of task configurations and $$$\lambda_{\ell_1}$$$ is the relative weighting for $$$\ell_1$$$ loss.

Datasets

FL experiments were performed on four multi-contrast MRI datasets: IXI (https://brain-development.org/ixi-dataset/), BRATS23, MIDAS24, and OASIS25. Subjects were split into non-overlapping training, validation, and test sets. 100 2D axial cross-sections containing brain tissues were selected from each subject.Implementation Details

Mapper was a fully-connected architecture with 6 layers that produced $$$w^k_c \in \mathbb{R}^{512}$$$. Synthesizer followed a ResNet6 backbone with an encoder-bottleneck-decoder structure, whereas discriminator was a PatchGAN6. Models were implemented using PyTorch. Federated training was performed via Adam ($$$\beta_1 = 0.5,\beta_2 = 0.999$$$), learning rate=$$$2e-4$$$ for 150 rounds, each of which comprised 1 local epoch.Results

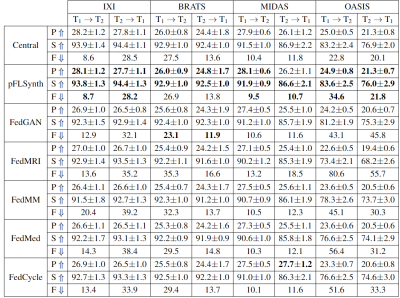

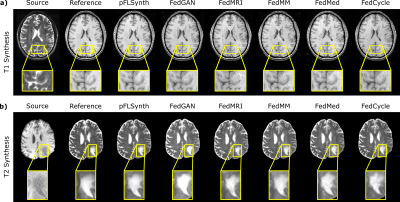

pFLSynth was compared against a centralized benchmark6 and federated baselines (FedGAN26, FedMRI27, FedMM21, FedMed19, FedCycle20). We demonstrated pFLSynth for simultaneous modeling of two tasks within each site, and the tasks were common across sites ($$$T_1\rightarrow T_2$$$ and $$$T_2\rightarrow T_1$$$). Performance metrics for competing methods are listed in Fig. 4. pFLSynth outperforms all federated baselines at each site ($$$p<0.05$$$, signed-rank test), with few exceptions, while performing on par with the central benchmark. On average, pFLSynth achieves 1.0dB higher PSNR, 1.9% higher SSIM, and 7.4 lower FID than federated baselines. Representative images are shown in Fig. 5. Compared to baselines, pFLSynth synthesizes images with lower artifacts and noise. In particular, it more accurately depicts pathological tissue.Discussion

Previous FL studies on MRI translation use global architectures that are vulnerable to heterogeneities in the data distribution. To our knowledge, pFLSynth is the first FL method for MRI contrast translation that personalizes to individual sites and translation tasks. Experiments on multi-site MRI data show that pFLSynth significantly outperforms federated baselines, while attaining the performance bound of a central benchmark. Our findings indicate that, by enabling training on imaging data from various sources and protocols, pFLSynth enhances generalizability and flexibility in multi-site collaborations.Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a TUBITAK BIDEB, a TUBA GEBIP 2015 fellowship, a BAGEP 2017 fellowship.References

1. K. Krupa and M. Bekiesinska-Figatowska, “Artifacts in Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Pol. J. Radiol., vol. 80, pp. 93–106, 2015.

2. J. Denck, J. Guehring, A. Maier, and E. Rothgang, “Enhanced magnetic resonance image synthesis with contrast-aware generative adversarial networks,” Journal of Imaging, vol. 7, p. 133, 08 2021.

3. Wang G, Gong E, Banerjee S, Martin D, Tong E, Choi J, Chen H, Wintermark M, Pauly JM, Zaharchuk G. Synthesize High-Quality Multi-Contrast Magnetic Resonance Imaging From Multi-Echo Acquisition Using Multi-Task Deep Generative Model. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2020 Oct;39(10):3089-3099.

4. Lee, D., Moon, WJ. & Ye, J.C. Assessing the importance of magnetic resonance contrasts using collaborative generative adversarial networks. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 34–42 (2020)

5. Kim S, Jang H, Hong S, Hong YS, Bae WC, Kim S, Hwang D. Fat-saturated image generation from multi-contrast MRIs using generative adversarial networks with Bloch equation-based autoencoder regularization. Med. Image Anal. 2021 Oct;73:102198.

6. S. U. Dar, M. Yurt, L. Karacan, A. Erdem, E. Erdem, and T. Çukur, “Image synthesis in multi-contrast MRI with conditional generative adversarial networks,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 38, no. 10, pp. 2375–2388, 2019.

7. B. Yu, L. Zhou, L. Wang, Y. Shi, J. Fripp, and P. Bourgeat, "Ea-GANs: Edge-Aware Generative Adversarial Networks for Cross-Modality MR Image Synthesis," in IEEE Trans. on Med. Imaging, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 1750-1762, 2019.

8. Chartsias, A., Joyce, T., Dharmakumar, R., Tsaftaris, S.A., 2017. Adversarial image synthesis for unpaired multi-modal cardiac data, in: Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging. pp. 3–13.

9. H. Yang et al., "Unsupervised MR-to-CT Synthesis Using Structure-Constrained CycleGAN," in IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 39, no. 12, pp. 4249-4261, Dec. 2020

10. Y. Hiasa, Y. Otake, M. Takao, T. Matsuoka, K. Takashima, J. Prince, N. Sugano, and Y. Sato, “Cross-modality image synthesis from unpaired data using CycleGAN: Effects of gradient consistency loss and training data size,” ArXiv, abs/1803.06629, 2018.

11. O. Dalmaz, M. Yurt, and T. Çukur, “ResViT: Residual vision transformers for multi-modal medical image synthesis,” vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 2598-2614, Oct.2022

12. G. Elmas, S. U. Dar, Y. Korkmaz, E. Ceyani, B. Susam, M. Özbey, S. Avestimehr, and T. Çukur, “Federated learning of generative image priors for MRI reconstruction,” arXiv:2202.04175, 2022.

13. G. A. Kaissis, M. R. Makowski, D. Rueckert, and R. F. Braren, “Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging,” Nat. Mach. Intell., vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 305–311, 2020.

14. W. Li et al., “Privacy-Preserving Federated Brain Tumour Segmentation,” in Mach. Learn. Med. Imag., 2019, pp. 133–141.

15. P. Guo, P. Wang, J. Zhou, S. Jiang, and V. M. Patel, “Multi-institutional Collaborations for Improving Deep Learning-based Magnetic Resonance Image Reconstruction Using Federated Learning,” arXiv:2103.02148, 2021.

16. M. J. Sheller, G. A. Reina, B. Edwards, J. Martin, and S. Bakas, “Multi-institutional Deep Learning Modeling Without Sharing Patient Data: A Feasibility Study on Brain Tumor Segmentation,” in Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv., 2019, pp. 92–104.

17. X. Li, Y. Gu, N. Dvornek, L. H. Staib, P. Ventola, and J. S. Duncan, “Multi-site fMRI analysis using privacy-preserving federated learning and domain adaptation: ABIDE results,” Med. Image. Anal., vol. 65, p. 101765, 2020.

18. Q. Liu, C. Chen, J. Qin, Q. Dou, and P. Heng, “FedDG: Federated Domain Generalization on Medical Image Segmentation via Episodic Learning in Continuous Frequency Space,” in Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2021, pp. 1013–1023.

19. G. Xie, J. Wang, Y. Huang, Y. Li, Y. Zheng, F. Zheng, and Y. Jin, “FedMed-GAN: Federated Domain Translation on Unsupervised Cross-Modality Brain Image Synthesis,” arXiv:2201.08953,2022.

20. J. Song and J. C. Ye, “Federated CycleGAN for Privacy-Preserving Image-to-Image Translation,”arXiv:2106.09246, 2021.

21. A. Sharma and G. Hamarneh, “Missing MRI pulse sequence synthesis using multi-modal generative adversarial network,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 1170–1183, 2020.

22. X. Huang and S. J. Belongie, “Arbitrary style transfer in real-time with adaptive instance normalization,” Int. Conf. Comput. Vis., pp. 1510–1519, 2017

23. B. H. Menze et al., "The Multimodal Brain Tumor Image Segmentation Benchmark (BRATS)," in IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 1993- 2024, Oct. 2015.

24. E. Bullitt, D. Zeng, G. Gerig, S. Aylward, S. Joshi, J. Smith, W. Lin, and M. Ewend, “Vessel Tortuosity and Brain Tumor Malignancy,” Academic Radiology, vol. 12, pp. 1232–40, 11 2005.

25. J. LaMontagne, T. L. Benzinger, J. C. Morris, S. Keefe, R. Hornbeck, C. Xiong, E. Grant,J. Hassenstab, K. Moulder, A. G. Vlassenko, M. E. Raichle, C. Cruchaga, and D. Marcus,“OASIS-3: Longitudinal Neuroimaging, Clinical, and Cognitive Dataset for Normal Aging and Alzheimer Disease,” medRxiv:2019.12.13.1901490, 2019.

26. M. Rasouli, T. Sun, and R. Rajagopal, “FedGAN: Federated Generative Adversarial Networks for Distributed Data,” arXiv:2006.07228, 2020.

27. C.-M. Feng, Y. Yan, H. Fu, Y. Xu, and L. Shao, “Specificity-Preserving Federated Learning for Image Reconstruction,” arXiv:2112.05752, 2021.

Figures

pFLSynth is a federated learning method for personalized MRI translation. The proposed architecture has a mapper that generates task- and site-specific latents. Feature maps are modulated via novel personalization blocks (PB) inserted into the generator. To further promote site-specificity, partial network aggregation is exercised, via shared downstream but unshared upstream layers. Thanks to these design features, pFLSynth can provide reliable performance under implicit and explicit data heterogeneities.