0152

Diffusion tensor imaging on a 1.5T MR-Linac and comparison to a 3T diagnostic scanner in glioma patients

Liam S. P. Lawrence1, Rachel W. Chan1, James Stewart2, Mark Ruschin2, Aimee Theriault2, Sten Myrehaug2, Jay Detsky2, Pejman J. Maralani3, Chia-Lin Tseng2, Hany Soliman2, Mary Jane Lim-Fat4, Sunit Das5, Greg J. Stanisz1,6, Arjun Sahgal2, and Angus Z. Lau1

1Physical Sciences, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Department of Radiation Oncology, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Medical Imaging, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Department of Surgery, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Department of Neurosurgery and Paediatric Neurosurgery, Medical University, Lublin, Poland

1Physical Sciences, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Department of Radiation Oncology, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Medical Imaging, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Department of Surgery, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Department of Neurosurgery and Paediatric Neurosurgery, Medical University, Lublin, Poland

Synopsis

Keywords: Tumors, Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Diffusion tensor imaging was implemented on a 1.5T MR-Linac and used to scan ten glioma patients and four healthy volunteers. Mean diffusivity and fractional anisotropy (FA) measurements were compared to those at 3T in 35 glioma patients. FA values surrounding the tumour and in white matter structures (genu, splenium, and body of corpus callosum) were investigated for the detection of tumour infiltration and radiation-induced damage, respectively. There was no evidence of dose-dependent white matter changes, in contrast to previous literature. Peritumoural FA changes occurred more frequently for high-grade compared to low-grade gliomas.Introduction

Quantitative imaging on MRI-linear accelerators could be used to identify microscopic tumour or detect early signs of radiation damage for radiotherapy target adaptation in glioma.1,2 Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) may be useful for both purposes because of its sensitivity to white matter damage.3,4 In this abstract, we provide the first report of DTI in the brain on an MR-Linac. Our objective was to characterize the repeatability of DTI parameters mean diffusivity (MD) and fractional anisotropy (FA) on the MR-Linac and compare MR-Linac measurements to those of a 3T diagnostic MRI scanner. Additionally, we sought to replicate previous studies which used DTI to detect tumour infiltration and radiation-induced white matter damage.5–9Methods

Patients: Thirty-five glioma patients (16 high-grade, 18 low-grade, 1 not-otherwise-specified) were treated on a conventional linear accelerator and scanned with a 3T Philips Achieva (“MR-sim”) at treatment planning, fractions 10 and 20 (weeks 2 and 4), and one-month post-radiotherapy (week 10). Ten glioma patients (eight high-grade, one low-grade, one brainstem glioma) were treated and imaged on a 1.5T Elekta Unity MR-Linac. Dose schedules were 60 Gy/30 fractions, 54/30, 40/15, or 59.4/33. Four healthy volunteers were scanned on the MR-Linac.Data acquisition: MR-Linac DTI data were acquired with TRSE EPI (30 directions at b=500s/mm2, 3 b=0 images, TR/TE=5750/93ms, voxel size=3.0×3.0×3.0mm3, FOV=240×240×132mm3, Δ/δ=68.5/14.8ms, Gmax=15mT/m,10 scan time=6:25). One b=0 image with reversed phase-encoding was acquired for distortion correction (scan time=0:52). MR-sim DTI data were acquired with PGSE EPI (10 directions at b=1000s/mm2, 1 b=0 image, TR/TE=9145/108ms, voxel size=1.5×1.5×3.0mm3, FOV=240×192×177mm3, Δ/δ=53.0/17.6ms, Gmax=40mT/m,11 scan time=5:02).

Image processing: Pre-processing of DTI included susceptibility distortion correction,12 eddy current correction,13 skull stripping,14 co-registration to the earliest T1-weighted scan, and parameter fitting.15 Distortion correction was not performed for MR-sim DTI. The ICBM-DTI-81 atlas16 was warped to subject space to create white matter (WM) regions of interest (ROIs), including genu, splenium, and body of the corpus callosum (Figure 1). Automated segmentation created cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and contralateral “whole WM” ROIs. The planned radiotherapy dose distribution and contours (gross tumour volume, GTV, and clinical target volume, CTV) were aligned to subject space. A peritumoural zone (PTZ) was defined as the CTV excluding the GTV. CSF was excluded from all ROIs. WM regions were excluded if they were adjacent to the tumour or exhibited anatomical shift over time. The aligned dose distribution was converted to an equivalent17 2 Gy/fraction plan using $$$\alpha/\beta=2.5$$$Gy,5 and used to create “dose-binned” WM regions by the range of planned dose. Dose-binned regions smaller than 1 cm3 were excluded to avoid sensitivity to anatomical shifts. Registration and segmentation used FSL and ANTs.15,18–20

Statistics: The mean MD and FA within each ROI were used to compute percent changes relative to each patient’s earliest MRI session. The median MD and FA were computed across patients over the white matter regions receiving less than 20 Gy and compared between subject cohorts using a linear model with cohort and ROI as fixed effects. Repeated measurements were used to calculate the within-subject standard deviation (wSD) and coefficient of variation (wCV).21 Changes in WM regions and PTZ were evaluated by comparison with the repeatability coefficient $$$\%RC=2.77\times wCV$$$. PTZ changes were compared between high-grade and low-grade gliomas.

Results

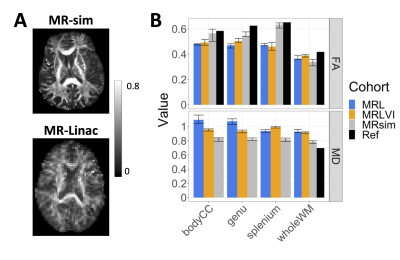

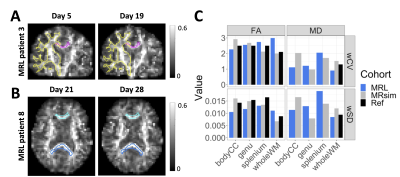

WM diffusion parameters differed between cohorts (Figure 2). On the MR-Linac, MD was lower in volunteers compared to patients (p<.001). Compared to MR-sim, the patient MR-Linac FA values were lower (p=.014) and the MD values were greater (p<.001).The wSDs and wCVs were comparable between the MR-Linac and MR-sim (Figure 3). The wCVs for FA in whole WM were 2.0% and 2.9% for the MR-sim and MR-Linac, respectively; therefore, the thresholds for significant change in the PTZ were set at $$$\%RC=\pm5.5\%$$$ and $$$\%RC=\pm8.1\%$$$, respectively.

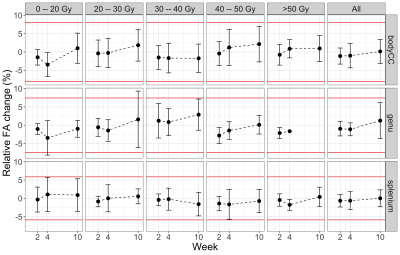

The WM structures did not show significant change in FA at weeks 2, 4, or 10 for most patients and there was no consistent dose-response relationship (Figure 4).

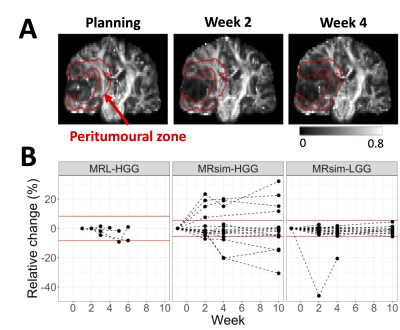

FA changes were detectable in the peritumoural zone (Figure 5). In 7 of 16 (44%) high-grade MR-sim patients, the peritumoural zone showed changes in FA at fraction 20 relative to treatment planning. In 1 of 5 (20%) high-grade patients with repeated scans on the MR-Linac, one showed significant change at week five relative to week one. The low-grade glioma patients did not show changes except for one, due to changes in edema.

Discussion

Compared to the 3T diagnostic scanner, the MR-Linac showed comparable repeatability but lower FA values. Potential reasons include CSF contamination,22 diffusion gradient timing,23 and gradient calibration.24We did not detect dose-dependent FA changes in WM structures within 10 weeks of radiotherapy initiation, in contrast to previous studies.5,6 Our data is consistent with other literature showing limited evidence of a dose-response relationship at early timepoints,25,26 further supporting that radiation-induced WM damage may not be detectable with DTI during radiotherapy.

In the peritumoural zone, more FA changes were seen in high grade patients compared to low-grade patients, concordant with previous literature showing reduced FA in high-grade gliomas relative to less- or non-infiltrative tumours.7–9

Conclusions

Diffusion tensor imaging on a 1.5T MR-Linac achieves comparable repeatability to a 3T diagnostic scanner and is sensitive to peritumoural changes potentially reflecting tumour infiltration.Acknowledgements

We thank the MR-Linac radiation therapists Shawn Binda, Danny Yu, Renée Christiani, Katie Wong, Helen Su, Monica Foster, Rebekah Shin, Khang Vo, Ruby Bola, Susana Sabaratram, Christina Silverson, Danielle Letterio, and Anne Carty for scanning and for their assistance with the protocol; Mikki Campbell for study coordination; Brian Keller and Brige Chugh for MR-Linac operations; and Wilfred Lam for data retrieval. We gratefully acknowledge the following sources of funding: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council; Terry Fox Research Institute; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute.References

1. Otazo R, Lambin P, Pignol JP, et al. MRI-guided Radiation Therapy: An Emerging Paradigm in Adaptive Radiation Oncology. Radiology. 2021;298(2):248-260. doi:10.1148/radiol.20202027472. Cao Y, Tseng CL, Balter JM, Teng F, Parmar HA, Sahgal A. MR-guided radiation therapy: transformative technology and its role in the central nervous system. Neuro-Oncol. 2017;19(suppl_2):ii16-ii29. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nox006

3. Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(3):316-329. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011

4. Price SJ, Gillard JH. Imaging biomarkers of brain tumour margin and tumour invasion. BJR. 2011;84(special_issue_2):S159-S167. doi:10.1259/bjr/26838774

5. Nagesh V, Tsien CI, Chenevert TL, et al. Radiation-Induced Changes in Normal-Appearing White Matter in Patients With Cerebral Tumors: A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2008;70(4):1002-1010. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.020

6. Connor M, Karunamuni R, McDonald C, et al. Dose-dependent white matter damage after brain radiotherapy. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2016;121(2):209-216. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2016.10.003

7. Provenzale JM, McGraw P, Mhatre P, Guo AC, Delong D. Peritumoral brain regions in gliomas and meningiomas: investigation with isotropic diffusion-weighted MR imaging and diffusion-tensor MR imaging. Radiology. 2004;232(2):451-460. doi:10.1148/radiol.2322030959

8. Price SJ, Burnet NG, Donovan T, et al. Diffusion Tensor Imaging of Brain Tumours at 3T: A Potential Tool for Assessing White Matter Tract Invasion? Clinical Radiology. 2003;58(6):455-462. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(03)00115-6

9. Wang W, Steward CE, Desmond PM. Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Glioblastoma Multiforme and Brain Metastases: The Role of p, q, L, and Fractional Anisotropy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(1):203-208. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A1303

10. Kooreman ES, van Houdt PJ, Keesman R, et al. ADC measurements on the Unity MR-linac – A recommendation on behalf of the Elekta Unity MR-linac consortium. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2020;153:106-113. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.046

11. Vannesjo SJ, Haeberlin M, Kasper L, et al. Gradient system characterization by impulse response measurements with a dynamic field camera: Gradient System Characterization with a Dynamic Field Camera. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(2):583-593. doi:10.1002/mrm.24263

12. Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage. 2003;20(2):870-888. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7

13. Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. NeuroImage. 2016;125:1063-1078. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019

14. Isensee F, Schell M, Pflueger I, et al. Automated brain extraction of multisequence MRI using artificial neural networks. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(17):4952-4964. doi:10.1002/hbm.24750

15. Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23:S208-S219. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051

16. Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, et al. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. NeuroImage. 2008;40(2):570-582. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035

17. Jones B, Dale RG, Deehan C, Hopkins KI, Morgan DA. The role of biologically effective dose (BED) in clinical oncology. Clin Oncol. 2001;13(2):71-81. doi:10.1053/clon.2001.9221

18. Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143-156. doi:10.1016/S1361-8415(01)00036-6

19. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved Optimization for the Robust and Accurate Linear Registration and Motion Correction of Brain Images. NeuroImage. 2002;17(2):825-841. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1132

20. Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Stauffer M, Song G, Wu B, Gee JC. The Insight ToolKit image registration framework. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:44. doi:10.3389/fninf.2014.00044

21. Raunig DL, McShane LM, Pennello G, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers: A review of statistical methods for technical performance assessment. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;24(1):27-67. doi:10.1177/0962280214537344

22. Jones DK, Cercignani M. Twenty-five pitfalls in the analysis of diffusion MRI data. NMR Biomed. 2010;23(7):803-820. doi:10.1002/nbm.1543

23. Bihan DL. Molecular diffusion, tissue microdynamics and microstructure. NMR Biomed. 1995;8(7):375-386. doi:10.1002/nbm.1940080711

24. Teh I, Maguire ML. Efficient gradient calibration based on diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:170-179.

25. Hope TR, Vardal J, Bjørnerud A, et al. Serial diffusion tensor imaging for early detection of radiation-induced injuries to normal-appearing white matter in high-grade glioma patients: Tracking early RBI with DTI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(2):414-423. doi:10.1002/jmri.24533

26. Rydelius A, Lampinen B, Rundcrantz A, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in glioblastoma patients treated with volumetric modulated arc radiotherapy: a longitudinal study. Acta Oncologica. 2022;61(6):680-687. doi:10.1080/0284186X.2022.2045036

27. Grech‐Sollars M, Hales PW, Miyazaki K, et al. Multi‐centre reproducibility of diffusion MRI parameters for clinical sequences in the brain. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(4):468-485. doi:10.1002/nbm.3269

Figures

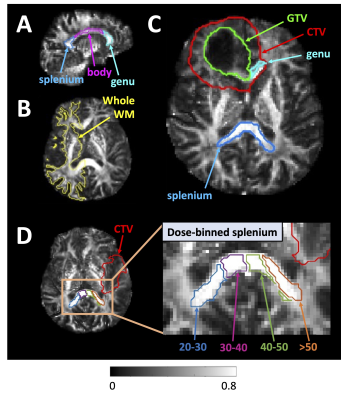

Figure 1 – Region of interest examples

overlaid on 3T MR-sim fractional anisotropy maps: (A): The splenium,

genu, and body of the corpus callosum (sagittal view). (B): A “whole

white matter” region contralateral to tumour. (C): The gross tumour

volume and clinical target volume (GTV and CTV) are close to/overlapping the genu;

hence, the genu was excluded from analysis for this patient. (D):

Dose-binned splenium example (dose ranges in Gy).

Figure 2 – Diffusion parameter values over

low-dose white matter regions: (A): Fractional anisotropy (FA) maps

from the 3T MR-sim and 1.5T MR-Linac (two different patients). (B): FA

and MD values over white matter regions. The solid bars show the median value,

and the error bars show the 25% and 75% quantiles across patients. MRL, MRLVI =

MR-Linac patient and volunteer imaging, MRsim = 3T diagnostic cohort, Ref = reference

values from literature.27

Figure 3 – Diffusion parameter

repeatability: Coronal and axial views of MR-Linac (MRL) FA maps for MRL patients

3 and 8 are shown in (A) and (B), as repeated measurement examples.

The contours are the body of the corpus callosum (bodyCC, magenta), whole white

matter (wholeWM, yellow), genu (cyan), and splenium (blue). (C): The

within-subject standard deviation and coefficient of variation (wSD and wCV)

over white matter regions receiving less than 20 Gy. Ref = reference values

from literature.27

Figure 4 – Fractional anisotropy changes

in white matter by dose bin for MR-sim: The fractional anisotropy changes

relative to treatment planning are shown for the genu, splenium, and body of

the corpus callosum (“bodyCC”) by dose bin. The points are means and the error

bars are standard deviations across patients. The number of patients per region,

dose bin, and timepoint varied. The horizontal red lines are the percent

repeatability coefficients. The “All” column is the entire ROI.

Figure 5 – Fractional anisotropy changes

in the peritumoural zone: (A): Coronal views of fractional

anisotropy maps from a grade 4 glioblastoma patient scanned on the MR-sim. The

peritumoural zone is delineated in red. Decreasing anisotropy is visible. (B):

FA changes relative to the earliest MRI timepoint per patient for high-grade

and low-grade gliomas (HGG and LGG) on the MR-Linac and MR-sim. There were no

MR-Linac LGG patients with multiple scans.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0152