0150

Tumour virtual histology with Magnetic Resonance Elastography1INSERM - King's College, Paris, France, 2School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Diagnostic Physics, Division of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 5U1021 INSERM, Institut Curie, Paris, France, 6Department of Radiology Ullevål, Division of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine,, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway, 7Department of Neurosurgery, Division of Clinical Neuroscience,, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway, 8Department of Neuroradiology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Tumors, Elastography

The reciprocal interaction between cancer cells and the surrounding creates a tumorigenic feedback loop capable of shifting the anti-neoplastic feature of the microenvironment towards a tumour growth-promoting one. Unfortunately infiltrating tumours, like GBMs, do not have discrete boundaries and intra-axial metastases are not visible on conventional MR images. However they are expected to change the tissue biomechanics. Here we explored tumour microenvironment biomechanics non-invasively using MRE in a cohort of 23 patients with brain tumours - 13 meningiomas, 10 glioblastomas. We show how MRE provides a comprehensive characterization of the tumour microenvironment, explaining histological features and tumour invasive features.Introduction

Tumour-induced tissue stiffness changes, arising from intratumoural fibrosis and extra cellular matrix metamorphosis, together with tumour pressure increase, have been reckoned as a key biomechanical fingerprint of tumours [1-2]. Tumour extracellular matrix is composed by collagen, elastic fibres, such as fibronectin and lamin, and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). All these elements not only provide the tumour’s scaffold but are also essential for the tumour growth and spread [3]. The reciprocal interaction between cancer cells and the surrounding creates a tumorigenic feedback loop capable of shifting the anti-neoplastic feature of the microenvironment towards a tumour growth-promoting one [4-5].Accessing non-invasively biomechanics could be fundamental to understand the physical cues at the base of cancer development. Recent studies on patient-derived tumour cell lines have shown how the elasticity of the substrate where the cells were growing, strongly influences the tumour migration capability [6-8]. For example, the invasive propensity of many glioblastomas (GBMs) lines is enhanced by peritumoural stiffness increase. Oppositely, the migration capacity of some other GBMs cell lines seems insensitive to the substrate biomechanics [9].

Furthermore, mechano-transduction may play a crucial role also in the determination of the tumour dissemination path; for example GBMs disseminate mainly along myelinated nerve fibres in the soft white matter or along the stiffer basement membrane that surrounds blood vessels [9].

Unfortunately infiltrating tumours, like GBMs, do not have discrete boundaries (as seen in histology) and intra-axial metastases are not visible on conventional MR images. However they are expected to produce greater disruption in the white matter tracts than non-infiltrative meningiomas (MENs), and therefore to change the tissue biomechanics [10].

In this work we explored tumour microenvironment biomechanics non-invasively using Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) in a cohort of 23 patients with brain tumours - 13 MENs, 10 GBMs. We show how MRE provides a comprehensive characterization of the tumour microenvironment which could explain histological features and therefore tumour invasive features.

Methods

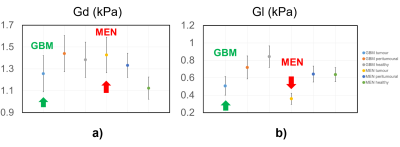

Imaging was performed on a 3T MRI (Signa Premier, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using a 48-channel head coil. A gravitational transducer [11] placed underneath the subject’s head induced shear waves at 50 Hz. The MRE acquisition was performed with a multishot gradient-echo sequence using Hadamard encoding [12]. Data inversion [13], allowed to calculate the complex shear modulus G*=Gd +iGl, where Gd is the shear stiffness, Gl is the shear viscosity, and $$$ Y=2/π*atan(Gl/Gd) $$$ in [0,1] is the phase angle [12]. Three regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn for each patients, enclosing the tumor, the peritumoural region and a contralateral region (as a healthy reference). Values of the biomechanical parameters are given as mean and standard deviation.Results and discussion

In Figure 1 the phase angle of tumour, peritumoural and healthy tissue for GBMs and MENs patients is plotted. Our 1st observation is that the phase angle of GBMs is statistically higher than the one of MENs. This biomarker, mathematically linked to the ratio of Gl and Gd, embeds the histological features of the two different tumours (Figure 2). In fact GBMs have a higher shear stiffness than the MENs (Figure 3 a). This trend mirrors the histological features: collagen fibres and fibrillary structures are very abundant in MENs, while confined in the perivascular space only in GBMs [14]. Furthermore GBMs have on average higher viscosity then MENs (Figure 3 b). This observation is justified by the higher GAG-related water content of GBMs with respect to MENs [14]. These histological features fully explain the behaviour of Y in the two tumour types.The 2nd observation is related to the peritumoural tissue. In GBMs peritumoural tissue features a phase angle between that of the tumour and of the healthy tissue, whereas MENs peritumoural tissue has a phase angle similar to the healthy tissue and distinct from the one of the tumour. This behaviour reflects the highly infiltrative feature of GBMs, which actively modify the surrounding tissue, compared to the nodular MENs, which remain confined [10].

Conclusions

In this abstract we show how biomechanics captures the histological features of the tumour itself and of its surrounding, providing an invaluable biomarker of tumour infiltration, not visible on conventional MR images. This knowledge could be useful in planning the tumour resection surgery [15-16] as well as in the characterization of the tumour phenotype and consequent treatment.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] T Stylianopoulos et al., Cancer research 73 (13), 3833 (2013).

[2] DM Gilkes and D Wirtz, Nature Biomedical Engineering 1 (1), 1 (2017).

[3] P Yu et al., Current opinion in immunology 18 (2), 226 (2006).

[4] MR Zanotelli et al., in The Physics of Cancer: Research Advances (World Scientific, 2021), pp. 165.

[5] JA Joyce and JW Pollard, Nature reviews cancer 9 (4), 239 (2009).

[6] JK Mouw et al., Nature medicine 20 (4), 360 (2014).

[7] TA Ulrich et al., Cancer research 69 (10), 4167 (2009).

[8] SN Kim et al., Development 141 (16), 3233 (2014).

[9] TJ Grundy et al., Sci Rep 6 (1), 1 (2016).

[10] JM Provenzale et al., Radiology 232 (2), 451 (2004).

[11] JH Runge et al., Physics in Medicine & Biology 64 (4), 045007 (2019).

[12] SF Svensson et al., Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 53 (5), 1510 (2021).

[13] R Sinkus et al., NMR Biomed 31 (10), e3956 (2018).

[14] K-J Streitberger et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (1), 128 (2020).

[15] A Bunevicius et al., NeuroImage: Clinical 25, 102109 (2020).

[16] JD Hughes et al., Neurosurgery 77 (4), 653 (2015).

Figures