0133

Clinically Feasible Patient-Specific Targeting Method for Improved Quality-of-Life Outcomes from MRgFUS Treatment of Essential Tremor1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 4Neurosurgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 5Neurosurgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Tractography & Fibre Modelling, Neurosurgical Targeting

MRI-guided focused-ultrasound (MRgFUS) is an FDA-approved treatment for essential tremor. Unfortunately, the target to be ablated cannot be directly visualized on standard imaging, and its location varies interindividually. Since suboptimal lesion location can lead to side effects that impair quality of life, a method that locates personalized ablative targets that correlate with better quality-of-life outcomes (and not just with tremor reduction) could provide significant benefit. We present a clinically-feasible patient-specific probabilistic-tractography-based method for personalized targeting of MRgFUS treatment and show that similarity between the target it generates and the ablated lesion predicts QoL outcome in a dataset of 36 patients.Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is a neurological disorder that causes involuntary, rhythmic shaking, especially when trying to do simple tasks such as drinking from a glass or writing. Tremor can be suppressed by stimulating or lesioning the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus, which relays signals from the cerebellum to the cortical motor pathways. MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) ablation of the VIM is an FDA-approved, minimally invasive treatment for ET. However, the VIM cannot be visualized directly on standard imaging, and the nuclear parcellation of the thalamus (and thus the location of the ideal ablative target) varies between individuals1,2. Ablating neighboring structures may cause side effects, such as sustained loss of balance in 18% of patients, that adversely impact quality-of-life (QoL)3,4. Therefore, there is a need for patient-specific methods to locate the “go-zone” for MRgFUS ablation for ET.Diffusion MRI (dMRI) tractography shows promise in locating the VIM within each patient’s thalamus based on structural connectivity to the primary motor cortex (M1)5-8. However, prior studies used deterministic tractography, which is not robust to crossing fibers, or probabilistic tractography on high-resolution dMRI datasets, which are not typically available clinically. In addition, they looked at tremor suppression alone, which is not predictive of QoL outcome4. Here, we present a clinically feasible patient-specific probabilistic-tractography-based method for targeting of MRgFUS for ET and show that similarity between the target it generates ("go-zone”) and the ablated lesion correlates with QoL outcome.

Methods

We retrospectively studied 36 subjects treated with MRgFUS at Stanford who had follow-up at least 90 days post-procedure. Before and after the MRgFUS procedures, T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and diffusion tensor images were acquired at 3T. On each subject’s standard, clinical preoperative dMRI (scan time<5m; 0.98mmx0.98mmx2mm resolution; 30 diffusion directions; b-value=1000s/mm2), probabilistic tractography was performed using FSL9.FSL’s “topup” and “eddy” tools were used to estimate and correct for susceptibility, eddy current, and motion artifacts in the dMRIs10-11. ANTs12 was used to compute a nonlinear transformation registering the MNI152 template13 to each patient's preoperative T1-weighted image. The thalamus and M1 regions-of-interest (ROIs) in MNI space were warped to fit each patient’s MRIs using this transform, and they then served as the seed and terminus, respectively, for tractography. Streamlines from the thalamus to M1 were then identified14, generating a patient-specific probability map of the path of the upper portion of the cerebello-thalamic-cortical tract. Within the thalamus, the region with the highest number of probabilisitc streamlines connected to M1 is the tractography-defined target (i.e, the "go-zone" for MRgFUS ablation). This hotspot was normalized by the robust maximum (98th percentile intensity), and values above 0.9 were preserved.

The lesion was manually segmented in the postoperative T2-weighted MRI and transformed to the preoperative T1-weigthed MRI. The similarity between the “go-zone” and lesion was then quantified using the Sorensen-Dice coefficient, an overlap-based metric. Each subject’s postoperative QoL ("better," "approximately the same," or "worse") was determined from their last available follow-up. The "approximately the same" and "better" groups were combined for two-group comparison of Dice coefficients of "worse" versus "same"/"better" subjects (Mann-Whitney U test).

Two atlas-based approaches of locating the VIM provided comparisons to our personalized method of identifying the VIM network-hotspot. The DISTAL-atlas VIM, which some centers use to target deep brain stimulation15, was automatically fit to each patient’s MRI by applying the nonlinear MNI-to-T1 transform described above. In addition, NeuroShape is a semi-automated tool for identifying thalamic nuclei for MRgFUS targeting16. Visible outlines of the thalamus were manually delineated, and NeuroShape generated a probability map of the location of the VIM.

Results

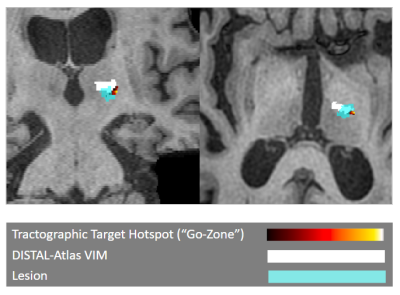

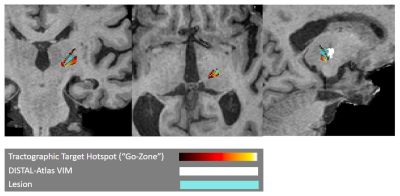

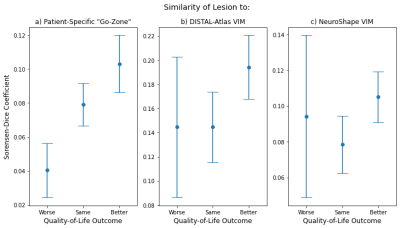

Probabilistic thalamus-to-M1 tracking robustly identified cerebello-thalamo-cortical tracts using standard, clinical dMRIs (Fig.1). Subjects with more positive QoL outcomes have lesions that are more similar to the “go-zones” generated by our method (Figs. 2-4). Dice coefficients of the "worse" group are significantly lower than of the "same"/"better" group (p=0.03). This is not seen with the DISTAL-atlas VIM (p=0.24) or Neuroshape VIM (p=0.21) .Discussion

In this work, we focused on quality-of-life outcomes after MRgFUS treatment of ET instead of tremor reduction alone. In an example patient with “worse” post-procedure quality-of-life (Fig. 2), the lesion ablated by MRgFUS does not coincide with the hotspot identified by our method but does overlap with the patient-fit DISTAL-atlas VIM. In the patient with “better” post-procedure quality-of-life (Fig. 3), the lesion overlaps with the brightest part of the hotspot, while the DISTAL-atlas VIM is anterior to both the “go-zone” and the lesion and thus only visible in the sagittal view. These examples suggest that atlas-based targeting may be inadequate for MRgFUS treatment of ET and that our method identifies “go-zones” which, if ablated, correspond with improved QoL.Since the proposed personalized MRgFUS targeting method uses only the standard anatomical and diffusion MRIs already acquired at most institutions, it may be easy to incorporate into current clinical workflows. In addition, our method is fully automated, making it less cumbersome than NeuroShape or commercially available tractography software.

Conclusion

We proposed a clinically feasible probabilistic-tractography-based targeting method for MRgFUS treatment of ET. Lesion similarity to the personalized “go-zone” is associated with better QoL outcome, unlike similarity to the DISTAL-atlas or Neuroshape VIM. This illustrates the value of our patient-specific targeting approach.Acknowledgements

Funding from the FUS Foundation helped support this project.References

1. Morel A, Magnin M, Jeanmonod D. Multiarchitectonic and stereotactic atlas of the human thalamus. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1997; 387:588–630.

2. Johansen-Berg H, Behrens TE, Sillery E, Ciccarelli O, Thompson AJ, Smith SM, Matthews PM. Functional–anatomical validation and individual variation of diffusion tractography-based segmentation of the human thalamus. Cerebral Cortex 2004; 15:31–39.

3. Lak AM, Segar DJ, McDannold N, White PJ, Cosgrove GR. Magnetic resonance image guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy. a single center experience with 160 procedures. Frontiers in Neurology 2022; 13.

4. Chodakiewitz Y, Purger D, Wang A, Barbosa D, Lev Tov L, Datta A, Bitton R, McNab J, Buch V, Ghanouni P. Smaller MRgFUS lesions that overlap patient-fit normative VIM—precentral tracts improve quality-of-life outcomes in essential tremor. In Proceedings of the Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB, London, England, UK, May 2022. p. 491.

5. Sammartino F, Krishna V, King NKK, Lozano AM, Schwartz ML, Huang Y, Hodaie M. Tractography-based ventral intermediate nucleus targeting: Novel methodology and intraoperative validation. Movement Disorders 2016; 31:1217–1225.

6. Tian Q, Wintermark M, Jeffrey Elias W, Ghanouni P, Halpern CH, Henderson JM, Huss DS, Goubran M, Thaler C, Airan R, Zeineh M, Pauly KB, McNab JA. Diffusion MRI tractography for improved transcranial MRI-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy targeting for essential tremor. NeuroImage: Clinical 2018; 19:572–580.

7. Krishna V, Sammartino F, Agrawal P, Changizi BK, Bourekas EC, Knopp MV, Rezai AR. Prospective tractography-based targeting for improved safety of focused ultrasound thalamotomy. Neurosurgery 2019; 84:160–168.

8. Agrawal M, Garg K, Samala R, Rajan R, Naik V, Singh M. Outcome and complications of MR guided focused ultrasound for essential tremor: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Frontiers in Neurology 2021; 12.

9. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. NeuroImage 2012; 62:782–790.

10. Andersson JL, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage 2003; 20:870–888.

11. Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, DeLuca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, DeStefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 2004; 23 Suppl 1:S208—19.

12. Avants B, Tustison N, Song G. Advanced normalization tools: V1.0. 2009.

13. Fonov V, Evans A, McKinstry R, Almli C, Collins D. Unbiased nonlinear average age-appropriate brain templates from birth to adulthood. NeuroImage 2009; 47:S102. Organization for Human Brain Mapping 2009 Annual Meeting.

14. Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Woolrich MW, Smith SM, Wheeler-Kingshott CAM, Boulby PA, Barker GJ, Sillery EL, Sheehan K, Ciccarelli O, Thompson AJ, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging. Nature Neuroscience 2003; 6:750–757.

15. Ewert S, Plettig P, Li N, Chakravarty MM, Collins DL, Herrington TM, Kuhn AA, Horn A. Toward defining deep brain stimulation targets in MNI space: A subcortical atlas based on multimodal MRI, histology and structural connectivity. NeuroImage 2018; 170:271–282. Segmenting the Brain.

16. Jakab A, Goey Z, Goksel O, Tuura R, Bauer R, Stieglitz L, Martin E, Szekely G. Neuroshape: a novel software implementing state-of-the-art targeting for MRI-guided focused ultrasound neurosurgery. 2018.

Figures

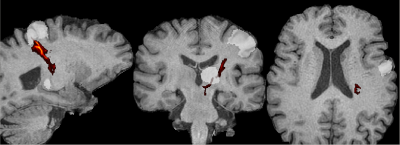

Figure 1. Probabilistic cerebello-thalamic-cortical tract (hot colors) generated by tracking from the thalamus to M1 (semi-transparent-white regions-of-interest) using a standard, clinical diffusion MRI. (Note that these slices show cuts through the tract, not a maximum-intensity projection, which is why the tract does not appear to connect the seed and terminus ROIs.)

Figure 4. Means of the Dice coefficients quantifying similarity between the ablated lesion and the targets generated by our method and by two comparison methods, with the error bars indicating ± the standard error of the mean. Unlike similarity to the patient-fit-DISTAL-atlas and NeuroShape VIM regions-of-interest (b and c), lesion similarity to the “go-zone” identified by the proposed personalized probabilistic-tractography-based method (a) is associated with better QoL outcome. This illustrates the value of our patient-specific targeting method for MRgFUS treatment of ET.