0118

Improving 3D-T1rho Mapping of the Human Brain Using Optimized Variable Flip-Angles and Weighted Spin-Lock Pulses1Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Pulse Sequence Design, optimization

This study shows 3D-T1rho mapping of the human brain using optimized variable flip-angles (OVFAs) and weighted spin-lock pulses (WSLP). Our preliminary results suggest that the proposed sequence based on OVFAs and WSLP can improve SNR by almost 3X in brain T1rho mapping, reduces data acquisition time by half, and improve the mean of normalized absolute deviation (MNAD) compared to MAPSS sequence for the same application.Introduction:

T1rho mapping is important in brain applications such as cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, and multiple sclerosis (1). We improve T1rho mapping, searching for good SNR with minimal filtering effects (2,3), by using a magnetization-prepared gradient echo (MP-GRE) sequences (4–6) with optimized variable flip-angles (OVFA) combined with Weighted Spin-Lock Pulses (W-SLP). We compare the proposed sequence against the commonly used magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled GRE snapshots (MAPSS) (4,7). The proposed sequence can improve SNR by almost 3X while reduce acquisition by half in brain T1rho mapping.Methods:

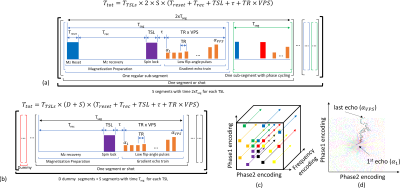

MP-GRE (8) and MAPSS (7) are sequences used for T1rho mapping. See Figure 1(a) and 1(b) respectively. MAPSS uses an Mz-reset pulse at each shot, followed by Mz recovery time (Trec), T1rho preparation, and an imaging echo train that acquires several k-space lines. The number of lines collected, or views-per-segment (VPS), and its center-out ordering (9) are shown in Figures 1(c) and (d). MP-GRE does not use the Mz-reset pulse, which allows for much smaller Trec. Because of it, MP-GRE requires some dummy segments (where no data is acquired) to reach a steady-state. MAPSS uses optimized flip-angles (FA) to reduce filtering effects (7). MP-GRE typically uses constant FA (CFA) (8). Here, we propose an optimization framework, that generalizes the optimization of MAPSS, considering not only reducing the filtering effects (2) but also improving SNR and T1rho accuracy. Data were acquired on a 3T Prisma MR scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany).T1rho relaxation is an exponential decaying process, such as T2 relaxation. This usually leads to a reduced SNR in T1rho-weighted images with long spin-lock times (TSLs). To compensate for it, we increase the brightness of the images by using larger initial flip-angles (FA) with long TSLs, which are usually darkened due to stronger T1rho-weighting. This would normally affect the fitting process. However, the weighting is considered as part of the optimization process and can be compensated after the acquisition, by adjusting the T1rho-weighted images back to their correct intensity. The advantage is that the image is captured with a stronger signal, yielding a better SNR after compensation.

The signal evolution (SE) model for MP-GRE sequences is given by (see (4) for SE of MAPSS):

$$M_{xy}(s,n)=A(n)M_{prep}(s)+B(n),$$

where $$$n$$$ represents the echo index and $$$s$$$ represents the shot position, and

$$A(n)=e_{\tau}\left[\prod_{i=1}^{n-1}e_1cos(\alpha_i)\right]e_2sin(\alpha_n)$$

and

$$B(n)=M_0\left\{(1-e_{\tau})\left[\prod_{i=1}^{n-1}e_1cos(\alpha_i)\right]+(1-e_{1})\left[1+\sum_{p=2}^{n-1}\left(\prod_{i=p}^{n-1}e_1cos(\alpha_i)\right)\right]\right\}e_2sin(\alpha_n)$$

where $$$e_{\tau}=e^{-\frac{\tau}{T_{1}}}$$$, $$$e_{1}=e^{-\frac{TR}{T_{1}}}$$$, $$$e_{2}=e^{-\frac{TE}{T2}}$$$, and

$$M_{prep}(s)=\left[M_z(s-1,VPS)e^{-\frac{T_{rec}}{T_{1}}}+M_0(1-e^{-\frac{T_{rec}}{T_{1}}})\right]e^{-\frac{TSL}{T_{1\rho}}}$$

where $$$1\leq n\leq VPS$$$, and:

$$M_{z}(s,n)=C(n)M_{prep}(s)+D(n),$$ With $$C(n)=e_{\tau}\left[\prod_{i=1}^{n}e_1cos(\alpha_i)\right],$$

$$D(n)=M_0\left\{(1-e_{\tau})\left[\prod_{i=1}^{n}e_1cos(\alpha_i)\right]+(1-e_{1})\left[1+\sum_{p=2}^{n}\left(\prod_{i=p}^{n}e_1cos(\alpha_i)\right)\right]\right\}$$

being $$$M_{prep}(1)=M_0e^{-\frac{TSL}{T_{1\rho}}}$$$.

We optimize the FA using:

$${\bf \hat{\alpha}}=\arg\min_{\alpha}\left[\sum_{k=1}^K\omega_k\left(\lambda_A||{\bf Am}_k(\alpha)||_2^2+\lambda_F||{\bf Fm}_k(\alpha)||_2^2+\lambda_S||{\bf S}({\bf m}_k(\alpha)-{\bf m}_{ref}||_2^2 \right)\right]$$

where $$${\bf m}_k(\alpha)$$$ in the normalized SE, $$${\bf m}_k(\alpha)=[M_{xy}(k,t_1,1,1)/(w(t_1)e^{-\frac{t_1}{T_{1\rho}(k)}})...M_{xy}(k,t_T,S+D,VPS)/(w(t_T)e^{-\frac{t_T}{T_{1\rho}(k)}})]$$$, being $$$M_{xy}(k,t,s,n)$$$ the SE with relaxation set $$$1\leq k\leq K$$$, where $$$K$$$ is the number of relaxation sets, considering $$$T_{1}(k),T_{2}(k),T_{1\rho}(k)$$$, for $$$1\leq t\leq T$$$, where $$$T$$$ is the number of TSLs, on the segment $$$1\leq s\leq S+D$$$, after the flip-angle pulse $$$1\leq n\leq VPS$$$.

We used $$$\omega_k=|T_{1\rho}(k)|^2/\sum_{i=1}^{K}|T_{1\rho}(i)|^2$$$. The first term targets accuracy, with the matrix $$$\bf A$$$ computes the finite difference between all pairs of $$$M_{xy}(k,t_p,s,1)/e^{-\frac{t_T}{T_{1\rho}(k)}}$$$ and $$$M_{xy}(k,t_q,s,1)/e^{-\frac{t_T}{T_{1\rho}(k)}}$$$, being $$$t_p$$$ and $$$t_q$$$ two different TSLs. The second term reduces the filtering effects, where the matrix $$$\bf F$$$ computes the finite difference on the SE inside the segment, and it is repeated for all TSLs. The third term targets a better SNR, where $$${\bf m}_{ref}$$$ is the reference signal, and the matrix $$${\bf S}$$$ has ones in the positions we want to be close to $$${\bf m}_{ref}$$$, and zeros on the others.

The optimization is weighted primarily to improve $$$T_{1\rho}$$$ accuracy first, secondarily to reduce filtering effects, and thirdly to improve SNR in MP-GRE sequences in configurations that make it faster than MAPSS. Note we also apply this framework to MAPSS itself (denoted by MAPSS-OVFA), to improve SNR.

The W-SLP changes the regular exponential decay to a weighted decay:

$$s(TSL)=w(TSL)e^{-\frac{TSL}{T_{1\rho}}}$$

Where the measured signal $$$s(TSL)$$$ at $$$TSL$$$ is weighted by $$$w(TSL)$$$. The weights are known, they are increasing with $$$TSL$$$, and are included in the normalized SE of the OVFA, usually leading to larger FAs for longer $$$TSL$$$. The inverse of weights is used to correct signal intensities after acquisition.

Results, Discussion:

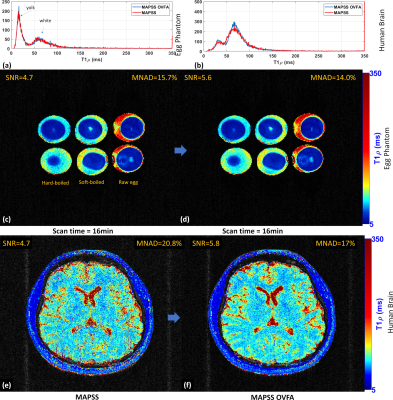

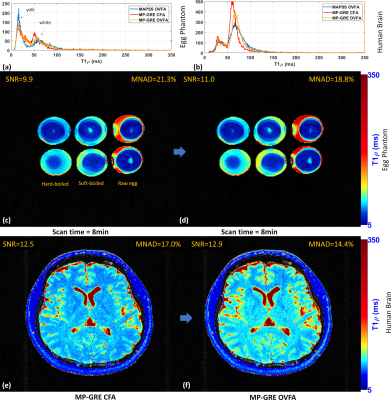

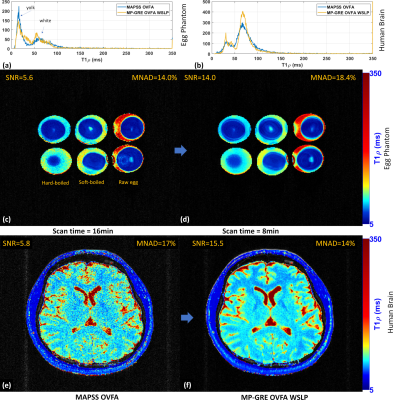

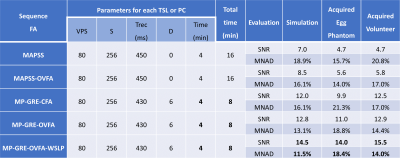

We compare the results visually and quantitatively (see Table 1) with SNR and the mean of the normalized absolute deviation (MNAD) (see (10) for details on how to compute them) in synthetic data, egg phantoms, and human brains. In Figure 2, we show the results with MAPSS and MAPSS-OVFA, to illustrate the improvement that OVFA can obtain in MAPSS. Because MAPSS-OVFA obtained the best quality it was chosen as the reference. In Figure 3, we compared the MP-GRECFA to MP-GRE-OVFA. In Figure 4, we illustrate a comparison of MAPSS-OVFA with MP-GRE-OVFA-WSLP, where it is clear how much improvement can be obtained in SNR.Conclusion:

The proposed sequence can improve SNR by almost 3X, reduce acquisition by half, and improved MNAD compared to MAPSS for brain 3D-T1rho mapping.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants, R21-AR075259-01A1, R01-AR068966, R01-AR076328-01A1, R01-AR076985-01A1, and R01-AR078308-01A1 and was performed under the rubric of the Center of Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), an NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center (NIH P41-EB017183).References

1. Haris M, Singh A, Cai K, et al. T1rho (T1ρ) MR imaging in Alzheimer’ disease and Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia. J. Neurol. 2011;258:380–385 doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5762-6.

2. Zhu D, Qin Q. A revisit of the k-space filtering effects of magnetization-prepared 3D FLASH and balanced SSFP acquisitions: Analytical characterization of the point spread functions. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2022;88:76–88 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2022.01.015.

3. Johnson CP, Thedens DR, Kruger SJ, Magnotta VA. Three‐Dimensional GRE T1ρ mapping of the brain using tailored variable flip‐angle scheduling. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020;84:1235–1249 doi: 10.1002/mrm.28198.

4. Peng Q, Wu C, Kim J, Li X. Efficient phase-cycling strategy for high-resolution 3D gradient-echo quantitative parameter mapping. NMR Biomed. 2022:1–19 doi: 10.1002/nbm.4700.

5. He L, Wang J, Lu Z-L, Kline-Fath BM, Parikh NA. Optimization of magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence for neonatal brain MRI. Pediatr. Radiol. 2018;48:1139–1151 doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4140-x.

6. Hargreaves B. Rapid gradient‐echo imaging. In: Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Vol. 36. ; 2012. pp. 1300–1313. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23742.

7. Li X, Han ET, Busse RF, Majumdar S. In vivo T1ρ mapping in cartilage using 3D magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled gradient echo snapshots (3D MAPSS). Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;59:298–307 doi: 10.1002/mrm.21414.

8. Sharafi A, Xia D, Chang G, Regatte RR. Biexponential T 1ρ relaxation mapping of human knee cartilage in vivo at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 2017;30:e3760 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3760.

9. Zibetti MVW, Sharafi A, Keerthivasan MB, Regatte RR. Prospective Accelerated Cartesian 3D-T1rho Mapping of Knee Joint using Data-Driven Optimized Sampling Patterns and Compressed Sensing. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of ISMRM 2021. ; 2021.

10. Zibetti MVW, Sharafi A, Regatte RR. Optimization of spin‐lock times in T1ρ mapping of knee cartilage: Cramér‐Rao bounds versus matched sampling‐fitting. Magn. Reson. Med. 2022;87:1418–1434 doi: 10.1002/mrm.29063.

Figures