0116

Accelerating Dynamic Imaging in SimulScan: Simultaneous Functional MRI and Dynamic Imaging of Tongue Motion1Bioengineering, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 2Carle Illinois College of Medicine, Urbana, IL, United States, 3Beckman Institute, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 4Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States, 5Neuroscience Institute, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, IL, United States, 6Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, fMRI (task based)

Leveraging low rank and Partial Separability models, the SimulScan sequence and reconstruction was updated to drastically improve the quality and speed of dynamic imaging. This enables simultaneous functional MRI and dynamic imaging of oropharyngeal motions to be examined despite the many air/tissue interfaces. We demonstrate the improvement on a healthy adult performing a self-paced tongue tapping during the scan. The improved imaging will enable the examination of neural control of fine scale articulatory and oral movements critical for speech, feeding, and swallowing events.Introduction

SimulScan provides a unique capability for simultaneous imaging of dynamic movements of the oropharyngeal region along with functional MRI of the brain for examining neural correlates of speech and swallowing motions1. Dynamic imaging of the oropharyngeal region is challenging due to the air/tissue interfaces requiring a high number of shots to limit distortions, which slows frame rates2. In its initial form, SimulScan was only able to provide an indication of large movements as the requirements for speed and multiple contrasts restricted the quality of the dynamic imaging that was obtainable with the method – for example, it was not able to visualize the tongue movement, it could only indicate that it was moving. However, recent advances in dynamic imaging, including the use of low rank and partial separability models with optimized temporal basis3,4, have enabled highly accelerated dynamic imaging with even sparser sampling of (k, t)-space to produce high quality dynamic images. Here we expand the SimulScan sequence to acquire temporal navigators and increase the image quality and speed for the dynamic imaging component.Methods

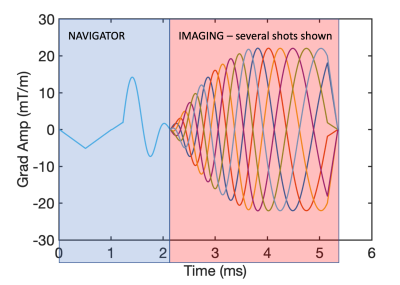

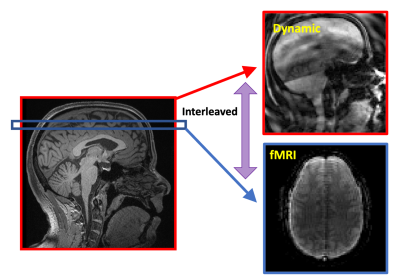

The Partial Separability (PS) model acquires a temporal navigator at each time point and then only one shot of the imaging data that highly undersamples (k, t)-space. After the temporal basis is determined from the temporal navigators with very high temporal resolution, the corresponding spatial basis of the PS model can be determined from the sparsely sampled imaging data across the time series. For this work, we designed a navigator that was one shot of a 24-shot, 64-matrix size spiral-in navigator. This was immediately followed by acquiring one shot of a 24-shot, 128-matrix size spiral-out imaging data. The navigator and imaging readouts were concatenated together as shown in Figure 1. SimulScan proceeds by acquiring one of these dynamic shots in between each 2D functional MRI slice (see Figure 2). The fMRI was a spiral-in, TE = 25 ms, 96 matrix size trajectory with a reduction factor of 2, reconstructed by SENSE5,6. We used a 38-slice fMRI acquisition with 3 mm slice thickness, fat sat on, resulting in an overall TR (fMRI slice and dynamic shot) of 76.6 ms, 13 fps dynamic imaging, and an overall TR for 38 slice fMRI data of 2.9 s. A healthy adult subject was scanned for 9.5 minutes and asked to tap their tongue several times during the course of the run, without cue and at their own pace, trying to get at least 20 taps in the run.Results

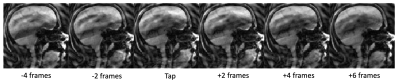

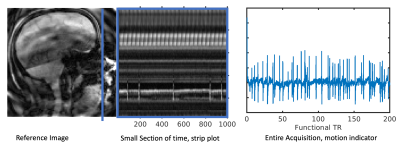

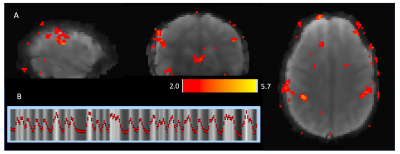

Figure 3 shows a strip of images (skipping every other frame for better visualization of motion) right before, during, and after a tongue tap. The 10 frames comprise 766 ms of total time. In this figure, you can clearly observe the tongue elevate to the alveolar ridge (front part of roof of the mouth) and return to its resting position. In order to create a time series of activity for fMRI analysis, a pixel was placed near the point of contact for the tapping and the mean signal was filtered and detrended to make an indication of the tongue tapping, shown in Figure 4. Figure 4 also shows the time plot for a strip of pixels through the tongue tip, showing the tongue push forward and upward as it elevates. Using the timings from the taps identified from the dynamic time series, a functional MRI analysis was conducted using FEAT7 in FSL on the functional MRI images. Activation in the sensorimotor tongue region is shown in Figure 5, along with some spurious motion-related activations.Discussion

Leveraging recent advances in dynamic imaging, SimulScan is able to provide high quality dynamic images of movement in the oropharyngeal region, enabling fMRI to be combined with fast, subject-driven oropharyngeal tasks. As shown in the strip plot in Figure 4, the method provides high temporal resolution to resolve the fast motions of a tongue elevating towards the roof of the mouth. No cued task was required as the SimulScan method was able to determine task timing from the simultaneously acquired dynamic images. The improved imaging will enable the examination of neural control of fine scale articulatory and oral movements critical for speech, feeding/sucking, and swallowing events.Conclusion

Combining simultaneous functional MRI and dynamic imaging with recent advances in dynamic acquisition and reconstruction, high quality dynamic images of the oropharyngeal tract can be obtained in between functional MRI slices in an oral motor fMRI task.Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DE027989. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views ofthe National Institutes of Health.References

1. Paine TL, Conway CA, Malandraki GA, Sutton BP. Simultaneous dynamic and functional MRI scanning (SimulScan) of natural swallows. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(5):1247-52.2.

2. Sutton BP, Conway CA, Bae Y, Seethamraju R, Kuehn DP. Faster dynamic imaging of speech with field inhomogeneity corrected spiral fast low angle shot (FLASH) at 3 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(5):1228-37.3.

3. Liang Z-P. Spatiotemporal imaging with partially separable functions. International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging2007. p. 988-91.4.

4. Jin R, Shosted RK, Xing F, Gilbert IR, Perry JL, Woo J, Liang ZP, Sutton BP. Enhancing linguistic research through 2-mm isotropic 3D dynamic speech MRI optimized by sparse temporal sampling and low-rank reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2022.5.

5. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: Sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:952-62.6.

6. Sutton BP, Noll DC, Fessler JA. Fast, iterative image reconstruction for MRI in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2003;22(2):178-88.7.

7. Woolrich MW, Ripley BD, Brady M, Smith SM. Temporal autocorrelation in univariate linear modeling of FMRI data. NeuroImage. 2001;14(6):1370-86.

Figures