0105

Migration of Potential Microstructural Markers of AD by High-Resolution Hippocampal Diffusion MRI

Courtney Joy Comrie1, Samantha Schatz1, Kevin Johnson1, Scott Squire1, Nan-kuei Chen1, and Elizabeth Hutchinson1

1Biomedical Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

1Biomedical Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Alzheimer's Disease

Diffusion MRI has been identified as a promising tool for identifying novel and early makers of AD and comorbid pathology. This study worked towards translating advanced microstructural techniques to clinical acquisitions for the purpose of potential AD diagnosis. High resolution diffusion human data was acquired using a 4-way phase-encoding and specialized hippocampal FOV in healthy subjects for method development. High quality maps were achieved that revealed more hippocampal microstructural information than what is acquired in database protocols according to preliminary results.Introduction

The identification of sensitive and specific brain imaging markers is a primary goal for neuroimaging in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). While advanced microstructural MRI approaches – especially non-Gaussian diffusion and multi-compartment relaxometry MRI methods – are conceptually appealing to report and differentiate cellular and macromolecular pathology, they have not been overly successful. Previously, we identified promising microstructural MRI markers in post-mortem tissue utilizing diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), neurite orientation dispersion imaging (NODDI), and mean apparent propagator (MAP)-MRI at high resolution and image quality 1, but for these observations of promising markers to become clinically relevant, it is essential to migrate high-resolution and high b-value acquisition for use in human patients. The objective of this study was to optimize a hippocampus-specific diffusion MRI acquisition paradigm and processing pipeline to enable translation of DTI, NODDI, and MAP-MRI methods from post-mortem study to in-vivo clinically feasible MRI protocols on a human MRI scanner.Methods

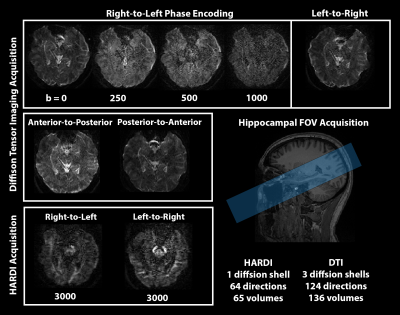

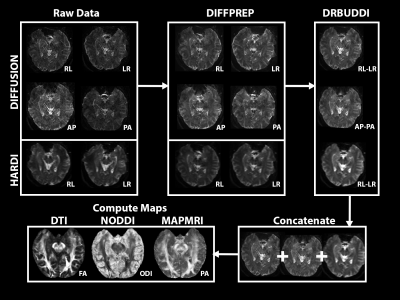

Healthy volunteers were recruited both for the MR battery development (n=9), and a test-retest reliability (n=5) acquisition where volunteers participated for two separate scan sessions to compare subject variability of microstructural MRI maps. Scans were developed on a 3T Skyra Siemens Scanner in the Translational Bioimaging Resources (TBIR) at the University of Arizona. A reduced field of view (FOV) strategy was used for all scans where slices were strategically placed according to the main axis of the hippocampus 2 and with 1x1x1.5mm voxel resolution. Efficient and high-quality diffusion MRI scans were the focus of development including 4PAT acceleration and 4-way phase acquisition (A-P, P-A, L-R, R-L) using bvalues 250, 500, and 1000 with 124 directions (figure 1) 3. A high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI) shell was also acquired with 2-way phase acquisition (L-R, R-L) with b=3000s/mm3, 64 directions, and voxel size of 2x2x3 mm (upsampled to 1x1x1.5mm during processing). Diffusion data were corrected for motion (DIFFPREP) and distortion (DRBUDDI) artifacts using TORTOISE 3.1.4 4 which combines all phase direction groupings (figure 2). All diffusion data was concatenated before estimating the diffusion tensor and mean apparent propagator to derive fractional anisotropy (FA), Trace (TR) 5 propagator anisotropy (PA), return-to-orgin probability (RTOP) 6. Additionally, neurite orientation dispersion density imaging (NODDI) was performed to estimate orientation dispersion index (ODI) 7. For analysis, a template was created using DTI-based registration (DRTAMAS) from the 10 diffusion tensor files of the test-retest dataset. A preliminary analysis was conducted on the FA and PA maps using two-way random intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC2) with hippocampal region of interests (ROIs). Additionally, observational differences were made between healthy volunteer FA maps collected from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) and our acquisitions methods.Results

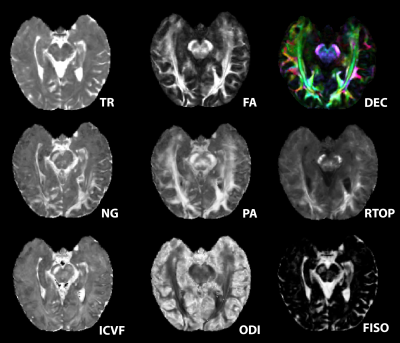

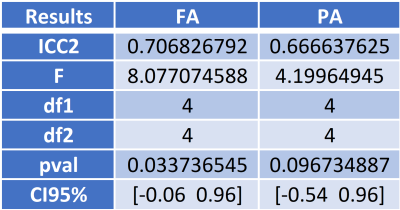

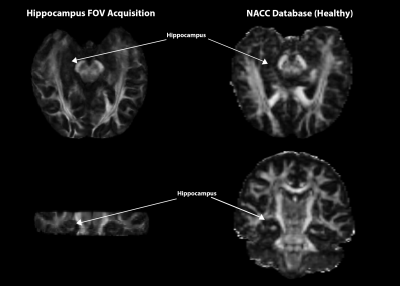

Desired quality and resolution were achieved for DTI, MAP-MRI, and NODDI maps using the reduced FOV strategy for high-resolution hippocampal imaging (figure 3). Preliminary results from ICC2 analysis for fractional anisotropy (FA), produced an ICC2 value of 0.71 and propagator anisotropy (PA) had an ICC2 of 0.67 (figure 4). Additional comparisons were made between an FA map calculated from a single healthy brain from the NACC and an FA map from a single volunteer in this study. More microstructural information is readily available in the hippocampus utilizing the methods in this study than in the techniques used by NACC databases (figure 5). The white matter track in the hippocampus was more apparent and detailed in data acquired in this study than the healthy brain from the NACC database.Discussion

Correction of geometric distortions and improvement in DWI image quality (i.e. SNR) were successful using 4-way phase correction and image re-combination. Additionally, MAP-MRI and NODDI modeling were both successful using the multi-shell and multi-resolution strategies developed in this study. Preliminary reproducibility data of the hippocampus in FA and PA showed low intraclass variability for participants with a ICC2. Providing promising initial results on the methods reliability with the desired image quality to visualize the hippocampus. Subjective comparison with conventional whole brain DTI from repository data demonstrated not only improved resolution with the proposed acquisition and pipeline, but also increase contrast of dMRI metric values in the hippocampus. The delineation of subfield values for advanced dMRI metrics (e.g. by MAP-MRI) may offer an important target to develop early AD markers and markers to distinguish among comorbid pathologies.Conclusion

High resolution and high-quality diffusion maps in DTI, NODDI, and MAPMRI was achieved through our developed acquisition methods and processing pipeline for hippocampal dMRI. Anisotropy metrics from DTI and MAP-MRI were reliable with subjects, which is essential for high quality mapping and future longitudinal patent studies. Translating promising metrics from post-mortem findings to human imaging, focused on the hippocampus provides potential methods for early diagnosis of AD. Future directions include comparison of this method with existing whole brain dMRI as well as direct comparisons with post-mortem tissue to improve the development of novel dMRI markers of AD.Acknowledgements

This work was generously supported by the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium. The authors thank the BME department, Translational Bioimaging Resource, and High Performance Computing (HPC) for providing the resources needed. A special thanks to all the MBSIL members, Maria Altbach, and Ali Bilgin for their support.References

- Comrie CJ, Dieckhaus LA, Beach T, Serrano G and Hutchinson EB. Microstructural MR Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in Post-Mortem Human Temporal Lobe. Oral Presentation. May 2022, ISMRM, London.

- Treit S, Steve T, Gross DW, Beaulieu C. High resolution in-vivo diffusion imaging of the human hippocampus. Neuroimage. 2018 Feb 1;182:479-487.

- Irfanoglu MO, Sadeghi N, Sarlls J, Pierpaoli C. Improved reproducibility of diffusion MRI of the human brain with a four-way blip-up and down phase-encoding acquisition approach. Magn Reson Med. 2021 May;85(5):2696-2708. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28624. Epub 2020 Dec 16. PMID: 33331068; PMCID: PMC7898925.

- Irfanoglu MO, Nayak A, Jenkins J, Pierpaoli C. TORTOISE v3: Improvements and New Features of the NIH. 25th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medcine. Published online 2017.

- Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994 Jan;66(1):259-67. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. PMID: 8130344; PMCID: PMC1275686.

- Avram AV, Sarlls JE, Barnett AS, et al. Clinical feasibility of using mean apparent propagator (MAP) MRI to characterize brain tissue microstructure. NeuroImage. 2016;127:422-434. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.027.

- Zhang, H., et al., NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. NeuroImage, 2012. 61(4): p. 1000-1016.

Figures

Figure 1: Diffusion acquisition methods used in this study with a targeted Hippocampal FOV. Four way phase acquisition with b=0-1000s/mm and 124 directions. Right-Left acquisition done with a HARDI shell b=3000s/mm3 and 64 directions.

Figure 2: Processing methods where Raw data is corrected for motion and distortions using TORTOISE 3.1.4 before concatenation and mapping.

Figure 3: Showcase of metrics from left to right DTI (trace TR, fractional anisotropy FA, directionally encoded color DEC), mean apparent propagator MAP (non-gaussianity NG, propagator anisotropy PA, return to origin propagator RTOP), NODDI ( intracellular volume fraction ICVF, orientation dispersion index ODI, free isotropic FISO).

Figure 4: Table for two-way intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC2), F statistic (F), numerator degree of freedom (df1), denominator degree of freedom (df2), p-value (pval), and 95% confidence intervals (CI95%) around the ICC2 for FA and PA.

Figure 5: Preliminary comparison between two healthy brains from this study's acquisition (left) and NACC database (right), registered to match targeted FOV. More hippocampal microstructural information appears to be more readily available within this study's acquisition methods.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0105