0098

IVIM-corrected DTI in acute hamstring injury in a clinically feasible acquisition time: a high-b DTI and multiband acceleration approach1Department of Biomedical Engineering and Physics, Amsterdam Movement Sciences, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) with correction for intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) is a potential biomarker to assess hamstring injury recovery and predict return-to-play time. However, the long acquisition times hinder the use in clinical practice. By accelerating in the b-value space and using multiband acceleration the scan time can be reduced to clinically acceptable levels. In this work we showed that those methods preserve the sensitivity to hamstring injuries and that high-b DTI in combination with multiband factor 2 can reduce the scan time to 3:40min.Introduction

Hamstring injuries are common in elite athletes and show recurrence rates of up to 30%1. Current qualitative imaging techniques such as T2-weighted MRI fail to predict a return-to-play time (RTP)2. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is sensitive to microstructural changes in skeletal muscle3,4 and might potentially be able to assess injury recovery and predict RTP in hamstring injuries. Intra-voxel incoherent motion causes additional signal decay, corrupting the DTI signal. Correction for IVIM effects increases the repeatability of DTI5 and yields additional information about perfusion. However, IVIM-corrected DTI requires long scan times which limits its clinical applicability.In this work we aim to accelerate IVIM-corrected DTI of acute hamstrings injuries to a clinically acceptable scan time while maintaining its sensitivity. For this purpose, we undersample IVIM-DTI scans in the b-value space and combine this with multiband (MB) acceleration.

Methods

58 patients with an acute hamstring injury (2f/56m, mean age 27.2±8.5 years) underwent MRI examination (3T Ingenia, Philips, Best, The Netherlands) within 7 days after the injury (baseline). 42 of those patients also received a follow-up MRI scan within 7 days after their RTP.The MRI protocol included an anatomical Dixon scan (1.5x1.5x2.5mm³, 80 slices, 6 echoes) and a SE-EPI IVIM-DTI scan (3x3x5mm³, 40 slices, TE/TR=55ms/5914ms, SPAIR and gradient-reversal fat suppression, SENSE=1.5) with 10 b-values (range 0-600s/mm², 8x b=0s/mm²) and 56 diffusion directions. For 7 patients, the IVIM-DTI scan at baseline and RTP was repeated with MB factor 2 (TE/TR=60ms/3365ms). The scan times were 11:08min for the IVIM-DTI scan and 6:20min for the MB IVIM-DTI scan.

The DTI data was denoised and registered to the Dixon images using QMRITools6. Injury center slices were determined by a radiologist and segmentations were drawn manually covering 7 slices in the DTI scan over the center slice in the injured muscle and a closely matching region in the contralateral healthy muscle in ITK-snap (www.itksnap.org). The diffusion tensor with IVIM correction was calculated using nonlinear least-squares fitting in Matlab (R2021a, The MathWorks, Natick, CA) with two different methods:

- IVIM-corrected

DTI:

This recently proposed method7 consists of four steps:

A. IVIM fit to the mean diffusion-weighted data

B. Voxel-wise IVIM fit with fixed pseudo-diffusion coefficient D* obtained from A.

C. Subtraction of the IVIM-component from the full signal.

D. DTI fit using all b-values to the remaining signal. - High-b

DTI:

We undersampled the data by discarding all b-values<200s/mm², resulting in b=200,400,600s/mm² and 32 diffusion directions to estimate the diffusion tensor. Assuming that the IVIM signal has fully decayed at b=200s/mm², the tensor is inherently IVIM corrected. The scan time is 6:27min without MB and 3:40min with MB.

Additionally, we estimated the IVIM perfusion fraction f with a two-step IVIM-DTI fit, fixing the diffusion tensor calculated with high-b DTI, and thereafter using all b-values for the IVIM fit.

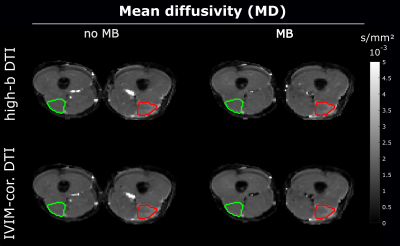

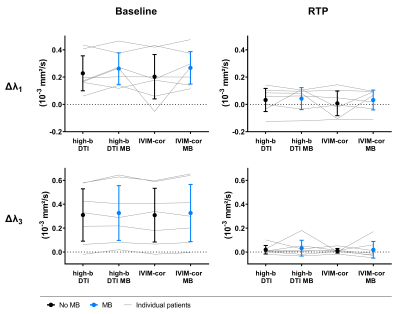

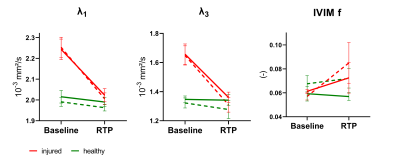

The outcome parameters for both methods were mean diffusivity (MD), fractional anisotropy (FA), diffusion tensor eigenvalues λ1, λ2, λ3, and IVIM-perfusion fraction (f). The Δ(injured-healthy) values per parameter and method were calculated as a measure of sensitivity to injury at baseline and RTP. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess differences in sensitivity between fitting methods and MB acceleration for each of the DTI parameters. Repeated measures Anova was used to assess if differences in injury state and between MB and non-MB parameters were significant (p≤0.05).

Results

Outcome parameters for fully sampled scans and accelerated scans using the various approaches were not significantly different (Figure 1). With high-b DTI the sensitivity to hamstring injuries could be preserved for all parameters both, with and without MB acceleration, compared to the IVIM-corrected DTI fit using all b-values (p>0.05, Figure 2).At baseline, significant changes between injured and healthy muscle were found in λ1, λ2, λ3 and MD with all methods, but not for FA and f. Interestingly, significant differences were also found at RTP; however, Figure 3 shows that the injured values converged towards healthy values at RTP. For all parameters and both injury states, no differences between MB and no-MB outcome parameters were found.

Discussion

In this work we demonstrated that sensitivity to hamstring injuries is preserved with our accelerated high-b DTI method and high-b DTI combined with MB undersampling. High-b DTI with MB factor 2 enables a scan time of less than 5 minutes, which makes this protocol suitable for clinical practice.FA and f did not show differences between injury states, indicating that those parameters are not sensitive to hamstring injuries. For the IVIM parameter estimation, we averaged over the diffusion directions and did not correct for T2 effects which could negatively impact the estimation. Therefore, incorporating a T2 correction8 or taking into account the anisotropy of the capillary network in skeletal muscle9 might be useful in the future. In the current setting, sampling of small b-values for IVIM parameter estimation seems redundant and high-b DTI in combination with MB factor 2 can be regarded the method of choice in hamstring injuries.

Conclusion

High-b DTI combined with MB factor 2 reduces the scan time to a clinically acceptable level and preserves the sensitivity to hamstring injuries.Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by the ‘National Basketball Association (NBA) & General Electric Healthcare (GEHC) Sports Medicine Collaboration, USA’.References

1. Orchard J, Best TM. The management of muscle strain injuries: An early return versus the risk of recurrence. In: Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. Vol 12. ; 2002:3-5. doi:10.1097/00042752-200201000-00004

2. Reurink G, Brilman EG, de Vos RJ, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Acute Hamstring Injury: Can We Provide a Return to Play Prognosis? Sport Med. 2014;45(1):133-146. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0243-1

3. Froeling M, Oudeman J, Strijkers GJ, et al. Muscle changes detected with diffusion-tensor imaging after long-distance running. Radiology. 2015;274(2):548-562. doi:10.1148/radiol.14140702

4. Hooijmans MT, Monte JRC, Froeling M, et al. Quantitative MRI Reveals Microstructural Changes in the Upper Leg Muscles After Running a Marathon. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2020. doi:10.1002/jmri.27106

5. Monte JR, Hooijmans MT, Froeling M, et al. The repeatability of bilateral diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in the upper leg muscles of healthy adults. Eur Radiol. 2019. doi:10.1007/s00330-019-06403-5

6. Froeling M. QMRTools: a Mathematica toolbox for quantitative MRI analysis. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4(38):1204. doi:10.21105/joss.01204

7. Schlaffke L, Rehmann R, Rohm M, et al. Multi‐center evaluation of stability and reproducibility of quantitative MRI measures in healthy calf muscles. NMR Biomed. July 2019. doi:10.1002/nbm.4119

8. Jerome NP, D’Arcy JA, Feiweier T, et al. Extended T2-IVIM model for correction of TE dependence of pseudo-diffusion volume fraction in clinical diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61(24):N667-N680. doi:10.1088/1361-6560/61/24/N667

9. Karampinos DC, King KF, Sutton BP, Georgiadis JG. Intravoxel partially coherent motion technique: Characterization of the anisotropy of skeletal muscle microvasculature. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(4):942-953. doi:10.1002/jmri.22100

Figures