0097

Sensitivity and Reproducibility of MRI Detection of Hourglass-Like Constrictions in Parsonage-Turner Syndrome1Department of Radiology and Imaging, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, United States, 2Hand and Upper Extremity Service, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, United States, 3Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States, 4Department of Physiatry, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurography, Nerves, Parsonage-Turner syndrome; electromyography

A retrospective analysis of 123 patients diagnosed with Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS; neuralgic amyotrophy) found that magnetic resonance neurography (MRN)-based detection of hourglass-like constrictions (HGCs) in affected nerves was 91.2-92.0% sensitive to electromyography-confirmed PTS. Post-hoc inter-rater reliability analysis revealed an inter-reliability of 91.3-94.3% for detection of HGCs. This retrospective study confirmed that MRN detection of HGCs is sensitive and reliable for diagnosing PTS and may be used as an objective diagnostic tool for the syndrome.Introduction

Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS or neuralgic amyotrophy) is a rare upper extremity neuropathy characterized by profound weakness1,2 that follows an intense, ipsilateral pain prodrome2,3. PTS is conventionally diagnosed with clinical signs and symptoms4–6, and with electromyography (EMG) to detect muscle denervation and to quantify motor unit recruitment (MUR)1,7. Hourglass-like constrictions (HGCs) of involved nerves/nerve fascicles in PTS have been identified via surgical exploration8–10, and recently, by magnetic resonance neurography (MRN)11–13 detection of focally reduced nerve calibers12 or a diffusely beaded appearance of the nerve14. However, the sensitivity and inter-rater reliability of MRN to HGCs have not been established in large PTS patient cohorts (>50) with objective assessment by EMG. This study aimed to determine if MRN-detected HGCs are sensitive and reliable to clinically diagnosed, EMG-corroborated PTS.Methods

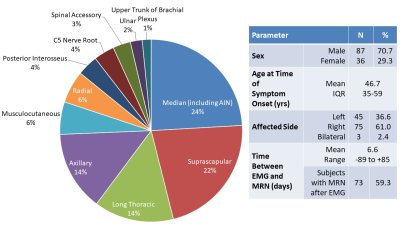

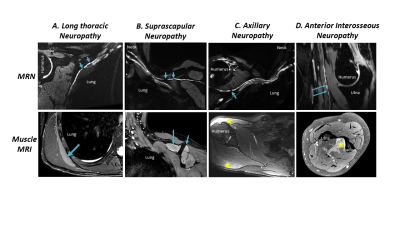

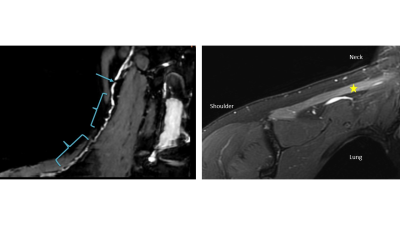

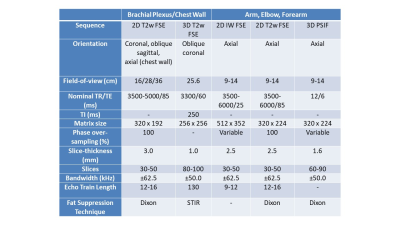

This retrospective study included 123 patients clinically diagnosed with PTS who underwent MRN at a single institution between 2011-2021. A total of 191 individual nerves were evaluated with MRN and had corresponding innervated muscles evaluated by EMG (Figure 1). The MRN was deemed ‘PTS positive’ if HGCs were described either as focally reduced nerve caliber (Figure 2) or as a beaded appearance of the nerve (Figure 3). The EMG was deemed ‘PTS positive’ if denervation (fibrillations and/or positive sharp waves) and impaired MUR (graded ‘none’ or ‘discrete’) were recorded. To assess post-hoc inter-rater reliability, a second radiologist, blinded to all clinical and EMG exams, independently graded HGCs for each nerve.3-Tesla MRN (GE MR750 or Premier) was performed using either a unilateral brachial plexus protocol or an extremity peripheral protocol11,15 targeting the involved nerves. Either two 16-channels coils (brachial plexus) or one 16-channel coil (extremity) were used. MRN pulse sequences included T2-weighted, fat-suppressed 2D and 3D acquisitions for peripheral nerve evaluation (Figure 4).

To assess MRN’s sensitivity to PTS by nerve, true positives (TP), false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), and true negatives (TN) of MRN were determined, with the clinical diagnosis of PTS confirmed by EMG criteria as the ground truth. To combine nerves from the same patient with conflicting TP/FP/FN/TN values, a patient was deemed TP if >1 nerve-muscle entry was TP. To evaluate differences in frequency distribution between EMG and MRN, Pearson’s chi-squared test with Yates’ continuity correction was performed. To assess post-hoc inter-rater reliability, the differences in frequency distribution between the radiologists were evaluated also with Pearson’s chi-squared test. Analysis was performed using R (The R Foundation, v4.0.3).

Results

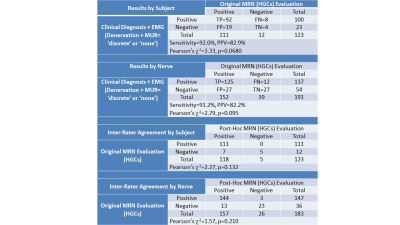

Analysis by subject (Figure 5) demonstrated a high sensitivity of 92.0% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 82.9%. There was no significant difference in the frequency distribution between MRN- and the EMG-confirmed clinical diagnosis (χ2=3.33, p=0.0680). Analysis by nerve also demonstrated a high sensitivity of 91.2% and PPV of 82.2% with no significant difference in frequency distribution (χ2=2.79, p=0.095). Among the FN nerve-muscle entries, most involved either bundles of the median nerve (6/12) or the long thoracic nerve (5/12). Among the FP nerve-muscle entries, 22/27 had a ‘reduced’ MUR reading.Two or more focal HGCs per nerve were observed within the same nerve in 93 subjects, one focal HGC was observed in 51 subjects, and 23 beaded appearances of HGCs of the nerve were noted. A total of 99.0% of MRN exams involved nerves with either abnormal signal intensity or size (hyperintense or enlarged), and/or muscles with a (denervation) edema pattern.

The second radiologist could confidently assess 183 of the 191 nerves (95.8%), with at least one nerve per subject. Post-hoc inter-rater agreement was 94.3% by subjects and 91.3% by nerves, with no significant difference in the frequency distribution between raters (subjects: χ2=2.27, p=0.132, nerves: χ2=1.57, p=0.210).

Discussion

MRN-detected HGCs were highly sensitive to PTS at rates similar to or higher than previous MRN reports involving smaller cohorts that did not always consider EMG criteria11,12. Inter-rater reliability of MRN HGC detection was also comparably high.EMG is an important diagnostic tool but has several limitations. Firstly, as EMG is typically not performed during the acute phase (it may take 3-4 weeks for denervation to be reliably detected by EMG), MRN may complement physical exams to confirm the clinical suspicion of PTS diagnosis. Along with under-recognition of the condition, this is likely one key factor contributing to the significant delay in time to diagnosis (an average of 44 weeks) for patients with PTS16.

HGCs have not been described in other spontaneous neuropathies (e.g., inflammatory or entrapment neuropathies)17,18, which suggests that HGCs may be specific to PTS. However, the specificity of HGCs was not evaluated in this study as the subject cohort comprised only patients clinically diagnosed with PTS. As data was from a single institution, a selection bias may exist. There was also potential positivity bias for the MRN diagnosis of HGCs, as radiologists were likely to be alerted to a suspicion of PTS prior to interpretation. Future investigation into longitudinal comparisons of HGCs and EMG and of their severity will help elucidate recovery patterns.

Conclusion

MRN-based detection of HGCs was 91.2-92.0% sensitive to EMG-confirmed muscle denervation in PTS subjects with 91.3-94.3% inter-rater reliability.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge research support from the NIH (R21TR003033).References

1. Feinberg JH, Radecki J. Parsonage-Turner Syndrome. HSS J. 2010;6(2):199-205. doi:10.1007/s11420-010-9176-x

2. Alfen N van, Engelen BGM van. The clinical spectrum of neuralgic amyotrophy in 246 cases. Brain. 2006;129(2):438-450. doi:10.1093/brain/awh722

3. IJspeert J, Janssen RMJ, Alfen N van. Neuralgic amyotrophy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021 Oct 1;34(5):605-612.. doi:10.1097/wco.0000000000000968

4. Alfen N van, Eijk JJJ van, Ennik T, et al. Incidence of Neuralgic Amyotrophy (Parsonage Turner Syndrome) in a Primary Care Setting - A Prospective Cohort Study. Plos One. 2015;10(5):e0128361. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128361

5. Smith CC, Bevelaqua AC. Challenging Pain Syndromes Parsonage-Turner Syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Cli. 2014;25(2):265-277. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2014.01.001

6. Vanhoutte EK, Faber CG, Nes SI van, et al. Modifying the Medical Research Council grading system through Rasch analyses. Brain. 2012;135(5):1639-1649. doi:10.1093/brain/awr318

7. Feinberg JH, Nguyen ET, Boachie‐Adjei K, et al. The electrodiagnostic natural history of parsonage–turner syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(4):737-743. doi:10.1002/mus.25558

8. Pan Y, Wang S, Zheng D, et al. Hourglass-Like Constrictions of Peripheral Nerve in the Upper Extremity: A Clinical Review and Pathological Study. Neurosurgery. 2014;75(1):10-22. doi:10.1227/neu.0000000000000350

9. Krishnan KR, Sneag DB, Feinberg JH, Wolfe SW. Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome Reconsidered: A Critical Analysis Review. Jbjs Rev. 2020;8(9):e20.00011. doi:10.2106/jbjs.rvw.20.00011

10. Komatsu M, Nukada H, Hayashi M, Ochi K, Yamazaki H, Kato H. Pathological Findings of Hourglass-Like Constriction in Spontaneous Posterior Interosseous Nerve Palsy. J Hand Surg. 2020;45(10):990.e1-990.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2019.12.011

11. Sneag DB, Arányi Z, Zusstone EM, et al. Fascicular Constrictions above Elbow Typify Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome. Muscle Nerve. Published online 2019. doi:10.1002/mus.26768

12. Sneag DB, Rancy SK, Wolfe SW, et al. Brachial plexitis or neuritis? MRI features of lesion distribution in Parsonage–Turner syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2018;58(3):359-366. doi:10.1002/mus.26108

13. Kim DH, Kim J, Sung DH. Hourglass-like constriction neuropathy of the suprascapular nerve detected by high-resolution magnetic resonance neurography: report of three patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2019;48(9):1451-1456. doi:10.1007/s00256-019-03174-4

14. Filler AG, Maravilla KR, Tsuruda JS. MR neurography and muscle MR imaging for image diagnosis of disorders affecting the peripheral nerves and musculature. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(3):643 682. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2004.03.005

15. Sneag DB, Zochowski KC, Tan ET. MR Neurography of Peripheral Nerve Injury in the Presence of Orthopedic Hardware: Technical Considerations. Radiology. 2021;300(2):246-259. doi:10.1148/radiol.2021204039

16. Eijk JJJV, Groothuis JT, Alfen NV. Neuralgic amyotrophy: An update on diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Muscle Nerve. 2016;53(3):337-350. doi:10.1002/mus.25008

17. Miller TT, Reinus WR. Nerve Entrapment Syndromes of the Elbow, Forearm, and Wrist. Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(3):585-594. doi:10.2214/ajr.10.4817

18. Chalian M, Faridian-Aragh N, Soldatos T, et al. High-resolution 3T MR Neurography of Suprascapular Neuropathy. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(8):1049-1059. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2011.03.003

Figures