0096

Fibromyalgia associates with pain-promoting and inhibitory functional connectivity of the default mode network in psoriatic arthritis.1School of Infection & Immunity, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom, 2Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 3University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 4Aberdeen Biomedical Imaging Centre, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Brain Connectivity, Brain, fMRI (Resting State), Inflammation, Multimodal

Patients with the musculoskeletal disorder psoriatic arthritis improve their inflammation with current treatments but still experience pain. Previous neuroimaging findings have identified functional connectivity of the resting-state default mode network and we explored how such features associate with nociplastic pain using both agonistic and selective approaches. We observed increased connectivity between the default mode network and regions of the brain related to both increased pain intensity and decreased pain inhibition. The implications of such findings shift the focus onto targeting central pain pathways in people with psoriatic arthritis.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a painful immune-mediated disease that causes peripheral inflammation of the musculoskeletal system. Despite effective peripheral anti-inflammatory therapeutics, patients commonly remain debilitated by persisting pain of co-morbid fibromyalgia – the prototypical nociplastic pain disorder – is frequently present in people with PsA1, 2. We therefore hypothesis that centrally based nociplastic pain mechanisms explain persisting PsA pain. Dysfunctional connectivity of the default mode network (DMN) is commonly observed in fibromyalgia and is considered a neurobiological marker of nociplastic pain 3. Specifically stronger connectivity between DMN and insula positively associates with increased pain intensity, while stronger connectivity with frontal regions is related to the inhibition of pain. This is the first study to investigate neurobiological markers of nociplastic pain in PsA.METHODS

The study recruited participants with PsA who had active disease and measured their degree of nociplastic pain using the ACR 2011 FM criteria 4. The patients undertook scans on a 3 Tesla Siemens PRISMA (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using 32 channels phased-array head coil. These included a T1-weighted fast-field echo 3D structural images for normalization (TR = 2500 ms, TE = 2.88 ms, TI = 1070 ms, FA = 8°, FOV = 256 mm, with 176 slices, 1 mm3 iso-voxel) and and a functional images at rest using a T2*-weighted multiband EPI sequence (TR = 800 ms, TE = 30 ms, FA = 52°, FOV = 216 mm, acceleration factor 6, 60 slices, 440 volumes at 2.4 mm3 iso-voxel). Preprocessing and later analysis of the images were carried out using SPM12 within the functional connectivity CONN toolbox 5, running on MATLAB R2019b. Preprocessing inluded the default MNI pipeline by CONN: realignment, slice-timing correction, ART-based motion outlier detection using a z threshold (global signal) of 9 and movement threshold of 2 mm; functional and structural segmentation, MNI normalization and 8-mm FWHM smoothing. The DMN was constructed using independent component analysis (ICA) on the functional smoothed data and identified using an established template within the literature, all completed within the Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT) toolbox 6. To test whether DMN connectivity related to nociplastic pain, we estimated its connectivity with every voxel (Pearson r correlations of BOLD activity) and ran general linear models to test their association with fibromyalgia score (Figure 1). We also calculated the connectivity between the DMN and bilateral subdivisions of the insula and test whether it associated with fibromyalgia scores. All analyses corrected for age, sex, and multiple comparisons (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05). Spearman correlations are computed using R.RESULTS

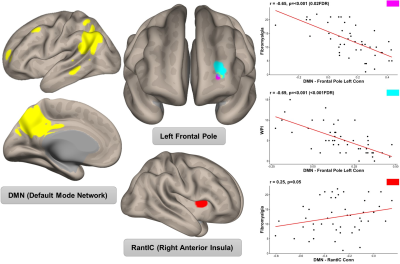

From 50 patients, 46 completed baseline MRI scanning, with clinical characteristics listed in Table 1. PsA patients with higher FM scores displayed increased connectivity between: 1) the DMN and the right anterior insula seed (R = 0.25, p ≤ 0.05) and 2) decreased connectivity between the DMN and the left frontal pole (R =-0.65, p < 0.001 FDR, peak voxel x= -20, y = 48, z = 4).| | Total (N=46) | FM- (N=26) | FM+ (N=20) |

| FM score | 12 (± 5.7) | 8.3 (± 3.4) | 18 (± 3.2) |

| Gender | | | |

| Female | 24 | 11 | 13 |

| Male | 22 | 15 | 7 |

| Age | 49 (± 11) | 48 (± 12) | 50 (± 9.7) |

| Pain modulation medication | | | |

| No pain modulation | 33 | 23 | 10 |

| Pain modulation | 13 | 3 | 10 |

| Disease activity Baseline | 41 (± 19) | 33 (± 13) | 51 (± 20) |

| Current pain (VAS) | 35 (± 23) | 31 (± 21) | 40 (± 26) |

Table 1: Clinical characteristics of patients with PsA, who completed an MRI scan, divided based being positive (FM+) or negative (FM-) for fibromyalgia, with a threshold of ≥ 13. Values are displayed as Mean±SD. VAS=visual analogue scale (0-100). Disease activity is measured using the DAPSA scale (Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis).

DISCUSSION

The connectivity results suggest that in patients with PsA, stronger nociplastic pain relates to connectivity promoting pain intensity (DMN-anterior insula) and weaker connectivity, associated with pain inhibition (DMN-frontal pole). Patients with higher fibromyalgia traits also tend to have weaker connectivity between the DMN and the frontal pole, which may be an indicator of failed inhibitory pathways. The study is limited by its cross-sectional analysis that could not delineate whether connectivity changes relate to nociplastic pain or any active interventions.CONCLUSION

This study provides the first objective evidence that nociplastic pain mechanisms contribute to pain in PsA. In consequence, approaches to reduce pain in this patient group should not be limited to peripherally directed analgesics but should also target central nociplastic pain substrates.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Boomershine CS. Fibromyalgia: The Prototypical Central Sensitivity Syndrome. Current Rheumatology Reviews 2015;11(2): 131-45.

2. Duffield SJ, Miller N, Zhao S, Goodson NJ. Concomitant fibromyalgia complicating chronic inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2018;57(8): 1453-60.

3. Reddan MC, Wager TD. Brain systems at the intersection of chronic pain and self-regulation. Neuroscience Letters 2019;702: 24-33.

4. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, et al. Fibromyalgia Criteria and Severity Scales for Clinical and Epidemiological Studies: A Modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. Journal of Rheumatology 2011;38(6): 1113-22.

5. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain connectivity 2012;2(3): 125-41.

6. Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pekar JJ. A method for comparing group fMRI data using independent component analysis: application to visual, motor and visuomotor tasks. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2004;22(9): 1181-91.

Figures

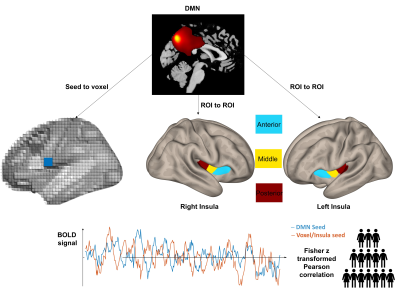

Figure 1: Connectivity analyses with FM scores using seed-to-voxel or region-of-interest (ROI) to ROI pipelines. The BOLD activity of the DMN is correlated with every voxel in the brain in an agnostic approach and 6 insula ROIs from the literature based on previous results in rheumatoid arthritis.

Figure 2: Results from connectivity analysis with the DMN and FM scores. Plots display spearman correlations between FM scores and connectivity between the DMN and cluster in the left frontal pole and the right anterior insula seed.