0080

TORTOISE V4: ReImagining the NIH Diffusion MRI Processing Pipeline1QMI/NIBIB, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2Henry Jackson Foundation, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Scientific and Statistical Computing Core, NIMH, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

The processing needs for diffusion MRI data have evolved over the years with data sizes getting larger, diffusion sensitization going higher. Large multi-site studies, especially on "uncooperative subjects" such as young children or patients with movement disorders increased the necessity for dMRI processing pipelines that are fast, robustly capable of handling a variety of artifacts/distortions, and that have summary reporting capabilities that can pinpoint problematic data. The NIH Diffusion MRI processing pipeline, TORTOISE, has been reimagined, redesigned and and significantly enriched to satisfy these processing needs.Introduction

Diffusion MRI (dMRI) data suffer from a number of artifacts and distortions including (but not limited to) low SNR, Gibbs ringing, bulk subject motion, within volume motion, eddy-current distortions, susceptibility-induced EPI distortions and ghost artifacts1,2. Appropriate pre-processing of diffusion weighted images prior to model fitting is vital for accurate quantitative analysis2,3. Over the years, the nature of dMRI data has evolved (smaller voxel sizes, significantly larger number of volumes and b-values, wider variety of acquisition paradigms...) as have the required processing tools. Additionally, large multi-site dMRI studies, on potentially "difficult" subjects (young children, geriatric populations, patients with movement disorders …), have increased the necessity for dMRI processing pipelines that are fast, robustly capable of handling a variety of artifacts/distortions, and that have summary reporting capabilities to pinpoint problematic data. TORTOISE (Tolerably Obsessive Registration and Tensor Optimization Indolent Software Ensemble)4 has been redesigned, made adaptable and significantly enriched to meet these needs.Materials & Methods

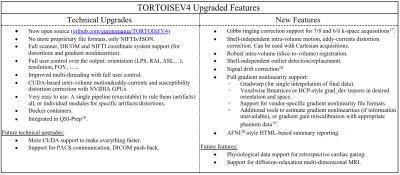

The Table in Figure1 lists the new features of the TORTOISEV4 pipeline. These features are new additions to the already existing ones such as denoising5, Gibbs ringing correction for full k-space acquisitions6, parsimonious inter-volume motion and eddy-currents correction7, blip-up blip-down susceptibility distortion correction using diffusion information8, diffusion tensor and MAPMRI9 computations and diffusion tensor-based diffeomorphic registration and atlas creation10.The slice-to-volume and outlier replacement is a new module in TORTOISEV4. These features generally require synthesis of predicted images, e.g., with Gaussian Processes in FSL-Eddy11 or multi-shell spherical harmonics12 in MRTrix. In our implementation, we employed the MAPMRI propagator model, which does not rely on shelled-data and is reasonably accurate while extrapolating for unseen q-vector signals even with Cartesian sampling. Our implementation starts with inter-volume motion&eddy-currents correction by aligning all DWIs to the ideal b=0s/mm2 image. Then until convergence: the MAPMRI model is estimated and used to synthesize an image for all q-vectors. For each volume and each multi-band slice group within the volume, the synthesized image's slice-groups are 3D-registered to the corresponding real image with a quadratic transformation (due to differences in EPI distortions). Subsequently, each synthesized slice-group is transformed backward to native slice-space, where slice-wise outliers are detected. For outlier detection, we use a similar approach to Christiaens et al.12.; however, instead of two clusters (inliers v.s. outliers) in Expectation-Maximization, we use four clusters, which are subsequently merged into two based on cluster statistics. We determined this approach to be more robust for data with residual distributions that cannot be accurately represented with two Gaussians. Subsequently, all native slice-space and outlier replaced images are forward transformed (with RBF interpolation using kd-trees) to their corresponding image’s space, where a final inter-volume motion and eddy-currents correction is performed, but this time, between synthesized and the slice-transformed/repol’ed real images. These steps are again repeated iteratively until convergence. We experimentally observed that three iterations are generally sufficient for most datasets.

The susceptibility distortion correction performance in TORTOISEV4 should be similar to previous versions with minor improvements for heavily distorted data. The most significant development for this module is the CUDA-based version, which can reduce the run-time from 3 hours to 10 seconds for very large datasets, with a powerful GPU.

Results

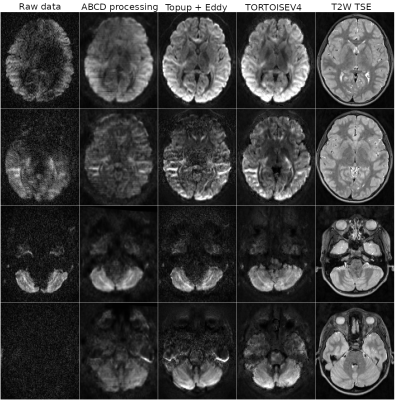

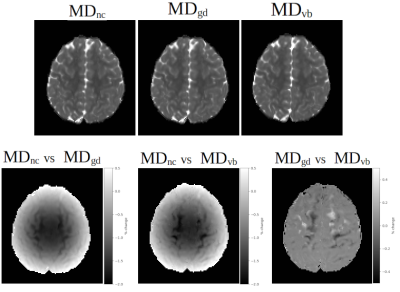

Figure2 displays the processing results from a single subject of the ABCD13 dataset to illustrate TORTOISEV4’s capabilities in slice-to-volume registration and outlier detection/replacement. This dataset was acquired using a Siemens Prisma 3T scanner. Each row displays results from a different problematic volume and slice due to extensive motion or cardiac pulsation. TORTOISEV4 was able to successfully detect and replace significant slice-wise and local dropouts.Figure3 displays the effect of gradient nonlinearity correction of TORTOISEV4, on mean diffusivity (MD) images. For this analysis, all three MD images were computed from identical diffusion weighted images, but with different B-matrix modalities. MDnc employed a constant B-matrix for all voxels (i.e. no gradient nonlinearity correction), MDgd used an HCP-style gradient deviation tensor, MDvb used voxelwise-Bmatrices, which not only considered the overall effects of nonlinearities, but also the interaction of motion with nonlinearities. All these options are available in TORTOISEV4. With both nonlinearity correction formats, a difference up to 2% was observed in MD relative to no correction. Interestingly, interaction between motion and nonlinearities also contributed up to 0.5% as indicated by the image labelled "MDgd vs MDvb".

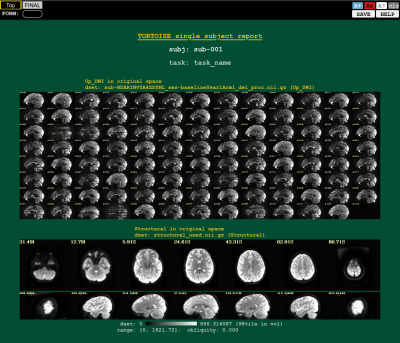

Figure 4 displays an example screenshot from one of the several the AFNI20-style quality control (QC) HTML summary reports. This report displays sagittal slices from different volumes of the original data and several slices from the anatomical image to summarize the artifact/distortion levels in the dataset. Visualizing not only final data but also raw and intermediate stage of processing greatly enhance the understanding and confidence in final results.

Discussion & Conclusions

The new TORTOISEV4, which can be downloaded from www.tortoisedti.org, or github.com/eurotomania/TORTOISEV4 has been significantly enriched with new features and made significantly faster. This new pipeline (or several of its modules) is already being or will be used for processing dMRI data from large studies including HCP14 (by our group), ABCD (by ABCD dMRI team) and HBCD15 (through QSIPREP16). Additional features such as more CUDA implementations, ghost artifact detection and correction are currently being developed and will be part of future releases.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Pierpaoli C. Artifacts in Diffusion MRI. In: Jones DK, editor. Diffusion MRI: Theory, Methods, and Applications OxfordUniversity Press; 2010.

2. Tax CMW, Bastiani M, Veraart J, Garyfallidis E, Irfanoglu M. Okan, What's new and what's next in diffusion MRI preprocessing. Neuroimage. 2022 Apr 1;249:118830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118830. Epub 2021 Dec 26. PMID: 34965454; PMCID: PMC9379864.

3. J. Veraart, et al. A data-driven variability assessment of brain diffusion MRI preprocessing pipelines. In: Proceedings of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; London, 2022.

4. Pierpaoli C, Walker L, Irfanoglu MO, Barnett AS, Chang LC, Koay CG, et al. TORTOISE: An integrated software package for processing of diffusion MRI data. In: Proceedings of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2010.p. 1597.

5. Veraart J, Fieremans E, Novikov DS. Diffusion MRI noise mapping using random matrix theory, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2016, 76 (5), 1582-1593.

6. Kellner E, Dhital B, Kiselev VG, Reisert M. Gibbs-ringing artifact removal based on local subvoxel-shifts. Magn Reson Med. 2016 Nov;76(5):1574-1581. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26054. Epub 2015 Nov 24. PMID: 26745823.

7. Rohde GK, Barnett AS, Basser PJ, Marenco S, Pierpaoli C. Comprehensive approach for correction of motion and distortion in diffusion-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2004 Jan;51(1):103-14. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10677. PMID: 14705050.

8. Irfanoglu MO, Modi P, Nayak A, Hutchinson EB, Sarlls J, Pierpaoli C. DR-BUDDI (Diffeomorphic Registration for Blip-Up blip-Down Diffusion Imaging) method for correcting echo planar imaging distortions. Neuroimage. 2015 Feb 1;106:284-99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.042. Epub 2014 Nov 26. PMID: 25433212; PMCID: PMC4286283.

9. Özarslan E, Koay CG, Shepherd TM, Komlosh ME, Irfanoglu MO, Pierpaoli C, and Basser PJ. (2013) Mean Apparent Propagator (MAP) MRI: a novel diffusion imaging method for mapping tissue microstructure. Neuroimage 78:16-32.

10. Irfanoglu MO, Nayak A, Jenkins J, Hutchinson EB, Sadeghi N, Thomas CP, Pierpaoli C. DR-TAMAS: Diffeomorphic Registration for Tensor Accurate Alignment of Anatomical Structures. Neuroimage. 2016 May 15;132:439-454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.066. Epub 2016 Feb 28. PMID: 26931817; PMCID: PMC4851878.

11. Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016 Jan 15;125:1063-1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019. Epub 2015 Oct 20. PMID: 26481672; PMCID: PMC4692656.

12. Christiaens D, Cordero-Grande L, Pietsch M, Hutter J, Price AN, Hughes EJ, Vecchiato K, Deprez M, Edwards AD, Hajnal JV, Tournier JD. Scattered slice SHARD reconstruction for motion correction in multi-shell diffusion MRI. Neuroimage. 2021 Jan 15;225:117437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117437. Epub 2020 Oct 14. PMID: 33068713; PMCID: PMC7779423.

13. Hagler DJ et al., Image processing and analysis methods for the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. Neuroimage. 2019 Nov 15;202:116091. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116091. Epub 2019 Aug 12. PMID: 31415884; PMCID: PMC6981278.

14. Van Essen DC, Ugurbil K, Auerbach E, Barch D, Behrens TE, Bucholz R, Chang A, Chen L, Corbetta M, Curtiss SW, Della Penna S, Feinberg D, Glasser MF, Harel N, Heath AC, Larson-Prior L, Marcus D, Michalareas G, Moeller S, Oostenveld R, Petersen SE, Prior F, Schlaggar BL, Smith SM, Snyder AZ, Xu J, Yacoub E; WU-Minn HCP Consortium. The Human Connectome Project: a data acquisition perspective. Neuroimage. 2012 Oct 1;62(4):2222-31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.018.

15. Healthy Brain and Child development Study, https://hbcdstudy.org/

16. Cieslak, M., Cook, P.A., He, X. et al. QSIPrep: an integrative platform for preprocessing and reconstructing diffusion MRI data. Nat Methods 18, 775–778 (2021).

17. Lee H, Novikov DS, Fieremans. Removal of Partial Fourier-Induced Gibbs (RPG) Ringing artifacts in MRI, In Proceedings of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2021, p.3537.

18. Vos SB, Tax CM, Luijten PR, Ourselin S, Leemans A, Froeling M. The importance of correcting for signal drift in diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2017 Jan;77(1):285-299. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26124. Epub 2016 Jan 29. PMID: 26822700.

19. Barnett AS, Irfanoglu MO, Landman B, Rogers B, Pierpaoli C. Mapping gradient nonlinearity and miscalibration using diffusion-weighted MR images of a uniform isotropic phantom. Magn Reson Med. 2021 Dec;86(6):3259-3273. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28890. Epub 2021 Aug 4. PMID: 34351007; PMCID: PMC8596767.

20. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996 Jun;29(3):162-73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. PMID: 8812068.

Figures