0053

Brain Ventricular and Microstructural Correlates of Executive Dysfunction in Congenital Heart Disease Using Explainable Machine Learning1Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 2Radiology, UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 3Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 4Radiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 5Learning and Development Center, Child Mind Institute, New York, NY, United States, 6Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Adolescents, Neuro, Congenital Heart Disease Neurodevelopment Machine Learning

This study examined cerebrospinal fluid volumes as neuroimaging features and their role in predicting specific executive function impairments among adolescents with congenital heart disease using explainable machine learning models. The findings showed CSF volumes were among the most important predictors of executive function inhibition domain with 3 CSF volumes ranked amongst the top 20, and 4 more CSF volumes among the top 20% of all features. Selective increased lateral ventricular volume in the frontal regions in CHD patients may be secondary to loss of white matter integrity in the uncinate fasciculus (emotional regulation) and subsequently lead to inhibitory dysfunction.INTRODUCTION

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume increase is a common finding in brains of fetuses and infants with congenital heart disease (CHD)[1-6] as well as in adults who had complex CHD[7]. Increased CSF has been associated with poor behavioral state regulation in neonates with CHD[8]. Several studies on adolescents with CHD have shown that brain volume reduction is associated with poor executive functions[9] and reduced hippocampal volumes are associated poor working memory[10], but analyses did not consider CSF. Beyond these studies, CSF volumes in adolescents with CHD and the role of CSF expansion in executive functioning impairments in CHD have remained largely unexplored. Data outside of CHD samples have shown that CSF volume increase, specifically in the lateral ventricles, predicts loss of inhibitory control in older adults[11]. The goal of this study was to examine CSF volumes as neuroimaging features and their role in predicting specific executive function impairments among adolescents with CHD using explainable machine learning models.METHODS

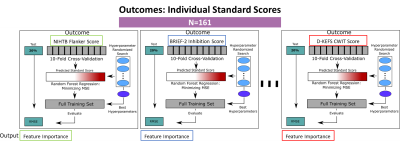

A total of 161 children and adolescents (CHD=69, 14.4±5.95 y.o.; Healthy Controls=92, 14.4±4.03 y.o.) from a prospective pediatric connectome study [Department of Defense grant reference: W81XWH-16-1-0613] with T1 and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) were included in this study. The scans were acquired on a Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) 3T Skyra system with 32-channel head coil. The T1 was acquired with the following parameters: TE/TR=3.2/2400 ms; matrix=256x256; Resolution 1.0x1.0x1.0 mm^3. The volumetric T1 weighted images were segmented – as outlined in Badaly and colleagues[12], using a combination of FreeSurfer[13, 14] and FSL FAST[15] – into cortical and subcortical regions, tissue regions, and CSF volumes delineated as left and right lateral ventricles (Left-LV and Right-LV), left and right lateral ventricle temporal horns (Left-TH and Right-TH), Third Ventricle, and Fourth Ventricle, extra-axial CSF, and whole brain CSF. DTI was acquired with the following parameters: TE/TR=92ms/12600 ms, matrix=128x128; Resolution 2.0x2.0x2.0 mm^3, and 42-directions at B=1000s/mm^2. The white matter tracts were generated using our in-house tractography pipeline as detailed in Meyers and colleagues[16]. The participants also completed neuropsychological testing. For this analysis, we focused on following domains of executive function: (1) Inhibition – assessed with Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Color-Word-Interference Test (CWIT), Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF-2) Inhibition subscale, and National Institute of Health Toolbox (NIHTB) Flanker Test; (2) Mental Flexibility – assessed with D-KEFS Trail Making Test Trial 4, Verbal Fluency Test Switching Accuracy, BRIEF-2 Shifting subscale, NIHTB Dimensional Card Change Sort Test; and (3) Working Memory – assessed with Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV) Letter-Number Sequencing, BRIEF-2 Working Memory subscale, and NIHTB List Sorting Working Memory Test.The CSF volumes along with other features (other brain volumes, white matter tractography, and participant demographics, clinical features, and CHD status totaling 435) were analyzed using random forest regression models. The random forest models were trained by maximizing the Gini gain (optimized by weighting the standard deviation reduction), and the hyperparameter selection schematic is presented in Figure 1. Post-hoc regression analysis among features were conducted for the top performing model by comparing CSF volumes that ascended to the top 20 ranked features against the executive function test in the model as well as the other top 20 features.

RESULTS

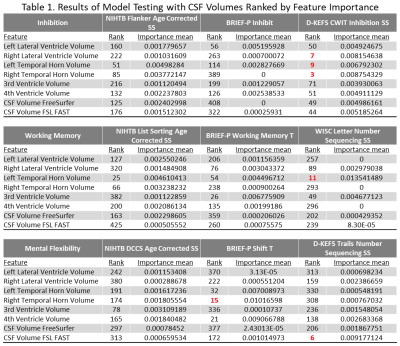

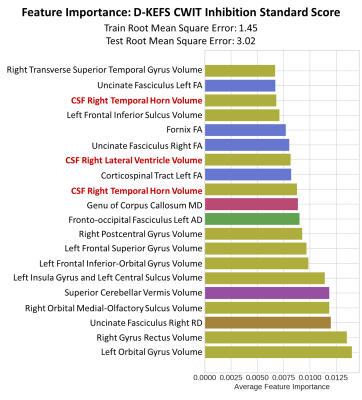

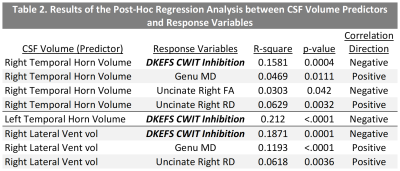

Results are presented in Table 1. CSF volumes had the highest feature importance for inhibition assessed with D-KEFS CWIT (Right-TH ranked 3, Right-LV ranked 7, and Left-TH ranked 9). This model was also the top performing model with the test root mean square estimate value of 3.02, and the top 20 features are presented in Figure 2. The post-hoc regression analysis results (Table 2) show that increased CSF volume in Left-TH (p<0.0001), Right-LV (p=0.0001), and Right-TH (p=0.0004) predicted poor performance on D-KEFS CWIT. Additionally, Increased Right-LV and Right-TH volumes also predicted decreased connectivity in Genu (demonstrated by increased medial diffusivity against: Right-LV p<0.0001, and Right-TH p=0.0111) and right uncinate fasciculus (demonstrated by increased radial diffusivity against: Right-LV p<0.0036, and Right-TH p=0.0032; and by decreased fractional anisotropy against Right-TH p=0.042). The CSF feature importance was next highest among mental flexibility (D-KEFS) and working memory (WISC-IV) domains. Models using BRIEF-2 ranked only one CSF volume as feature of high importance, and all models using NIHTB did not have CSF volumes among the top 20 ranks. Demographic factors, heart lesions, and CHD status did not emerge as features of high importance in any of these models.DISCUSSION

Our study showed that CSF volumes were among the most important predictors of cognitive inhibition with 3 CSF volumes ranked amongst the top 20, and 4 more CSF volumes among the top 20% of all features. These findings suggest that increased CSF volumes had greater contribution to poor executive function than whether the participant had CHD. Our finding of selective increased lateral ventricular volume in the frontal (frontal horn/anterior body lateral ventricle) and the temporal (temporal horns) regions in CHD patients may be secondary to loss of white matter integrity (or lingering dysmaturation) in the uncinate fasciculus (emotional regulation) and subsequently lead to inhibitory dysfunction.CONCLUSION

Increased CSF volumes might be promising neuroimaging features to predict executive function impairments. The random forest models proved an effective tool to extract critical features for neurodevelopmental studies in CHD.Acknowledgements

Grant Support from: Department of Defense [Grant reference: W81XWH-16-1-0613] and National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant reference: F31 HL165730-01].

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Radiology, Pediatric Imaging Research Center Personnel: Christine Johnson, Nancy H. Beluk

UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Department Radiology Staff

References

1. Heye, K.N., et al., Reduction of brain volumes after neonatal cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in single-ventricle congenital heart disease before Fontan completion. Pediatric research, 2018. 83(1): p. 63-70.

2. Panigrahy, A., et al., Brain dysplasia associated with ciliary dysfunction in infants with congenital heart disease. The Journal of pediatrics, 2016. 178: p. 141-148. e1.

3. Reich, B., et al., Interrelationship between hemodynamics, brain volumes, and outcome in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. The Annals of thoracic surgery, 2019. 107(6): p. 1838-1844.

4. Ortinau, C.M., et al., Prenatal to postnatal trajectory of brain growth in complex congenital heart disease. NeuroImage: Clinical, 2018. 20: p. 913-922.

5. Kelly, C.J., et al., Impaired development of the cerebral cortex in infants with congenital heart disease is correlated to reduced cerebral oxygen delivery. Scientific reports, 2017. 7(1): p. 1-10.

6. Ng, I.H., et al., Investigating altered brain development in infants with congenital heart disease using tensor-based morphometry. Scientific reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 1-10.

7. Cordina, R., et al., Brain volumetrics, regional cortical thickness and radiographic findings in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. NeuroImage: Clinical, 2014. 4: p. 319-325.

8. Owen, M., et al., Brain volume and neurobehavior in newborns with complex congenital heart defects. The Journal of pediatrics, 2014. 164(5): p. 1121-1127. e1.

9. von Rhein, M., et al., Brain volumes predict neurodevelopment in adolescents after surgery for congenital heart disease. Brain, 2014. 137(1): p. 268-276.

10. Latal, B., et al., Hippocampal volume reduction is associated with intellectual functions in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Pediatric research, 2016. 80(4): p. 531-537.

11. Lundervold, A.J., A. Vik, and A. Lundervold, Lateral ventricle volume trajectories predict response inhibition in older age—A longitudinal brain imaging and machine learning approach. Plos one, 2019. 14(4): p. e0207967.

12. Badaly, D., et al., Cerebellar and Prefrontal Structures Associated with Executive Functioning in Pediatric Patients with Congenital Heart Defects. Frontiers in Neurology, 2022. 13.

13. Reuter, M., H.D. Rosas, and B. Fischl, Highly accurate inverse consistent registration: a robust approach. Neuroimage, 2010. 53(4): p. 1181-1196.

14. Reuter, M., et al., Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage, 2012. 61(4): p. 1402-1418.

15. Zhang, Y., M. Brady, and S. Smith, Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 2001. 20(1): p. 45-57.

16. Meyers, B., et al., Harmonization of multi-center diffusion tensor tractography in neonates with congenital heart disease: Optimizing post-processing and application of ComBat. Neuroimage: Reports, 2022. 2(3): p. 100114.

Figures