0049

Altered neurovascular coupling in children with idiopathic generalized epilepsy1Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, ZunYi, China, 2Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, BeiJing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Epilepsy, Neurovascular coupling

This study investigated the neurovascular coupling of children with idiopathic epilepsy using resting-state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and arterial spin labeling. Children with IGE present altered global neurovascular coupling, and higher regional neurovascular coupling in in the right medial frontal gyrus associated with lower performance intelligence quotient scores. The study shed a new insight into the pathophysiology of epilepsy and provided the potential imaging biomarkers of cognitive performances in children with IGE.Introduction

Pediatric epilepsy patients account for approximately 10.5 million cases, and the frequent seizures often affect the growth and development of these children1,2. Early diagnosis are critical to improve the prognosis of children with epilepsy. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) is a common subtype of pediatric epilepsy, which lack of objective biomarkers to make diagnosis. Basic research has confirmed that recurrent epileptic seizures can lead to neurovascular coupling (NVC) alteration, which may be a potential objective biomarker for IGE3-6. However, specific neuroimaging evidence of NVC alterations in children with IGE are still lacking. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the NVC alteration and its clinical significance in childhood IGE combining resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) and arterial spin labeling (ASL) and provide a new perspective to understand the neuropathological mechanisms of this disease.Methods

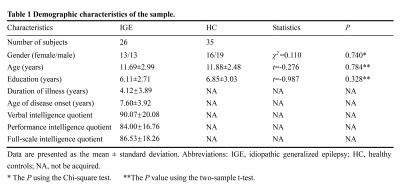

The study finally included 61 right-handed subjects (26 children with IGE and 35 healthy controls [HCs])(Table 1). The inclusion criteria for the case group were as follows: (1) clinically diagnosed IGE; (2) Conventional head MRI examination results were normal; and (3) age 6-16 years at the time of MRI scanning. The exclusion criteria were: (1) any other neurological disorders and/or history of malignant tumors or head trauma; (2) image artifacts affecting the image analysis; (3) history of substance abuse; and (4) head motion with maximum displacement >2 mm or >2° rotation noted during rs-fMRI data preprocessing. All participants underwent MRI scans using a 3.0-T magnetic resonance scanner (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The functional images were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence (TR: 2000 ms; TE: 30 ms; voxel size: 3.75 mm × 3.75 mm × 4 mm; FOV: 240 mm × 240 mm; slice number: 33; slice thickness: 4 mm; flip angle: 90°). The perfusion images were obtained with a pseudo-continuous ASL sequence (TR: 4599 ms; TE: 9.8 ms; slice number: 36; FOV: 256 mm × 256 mm; slice thickness: 4 mm; flip angle: 90°). Degree centrality(DC) and CBF were calculated based on the rs-fMRI and ASL. For each participant, across-voxel correlation analyses were performed between DC and CBF in the whole gray matter (GM) to quantitatively evaluate the global NVC. For all voxels, we calculated the CBF/DC ratio using the original values of CBF and DC, without z-transformations, to represent the regional NVC. The intergroup differences in CBF, DC, and CBF/DC ratio maps were analyzed using a voxel-wise two-sample t-test, adjusting for the covariates of age, sex, and years of education. For the resulting CBF, DC, and CBF/DC ratio maps, the Gaussian random field (GRF) method (P < 0.05) was selected to correct for multiple comparisons. The mean value of each cluster with significant between-group differences in CBF, DC, and CBF/DC ratio was extracted and correlated with the clinical variables using Pearson correlation.Results

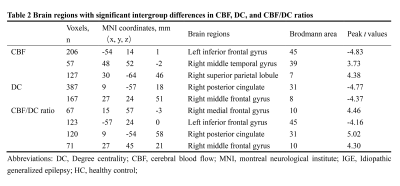

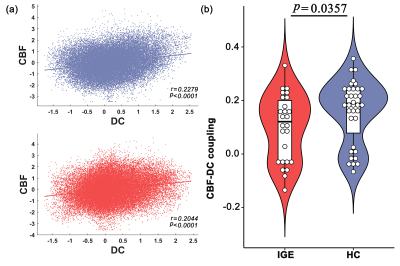

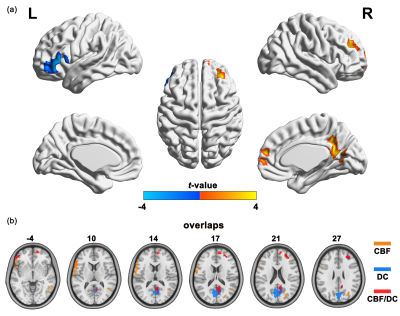

All subjects exhibited significant across-voxel spatial correlations between CBF and DC; two representative correlation maps (one from each group) are presented in Figure 1a; the CBF-DC coupling within the GM mask was significantly lower in the IGE group than in the HC group (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test; Figure 1b). The IGE group showed significantly higher CBF/DC ratio in the right medial frontal gyrus (MFG), posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus, and middle frontal gyrus, with significantly lower CBF/DC ratio in the left inferior frontal gyrus compared to the HC group (GRF corrected: P < 0.05); all results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2a. The IGE group also showed a significantly lower CBF than the HC group in the left inferior frontal gyrus, and a higher CBF in the right middle temporal gyrus and superior parietal lobule (GRF corrected: P < 0.05, Table 2). The IGE group exhibited a lower DC in the right posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and middle frontal gyrus compared to the HC group, though the brain region of DC difference was not reported (GRF corrected: P < 0.05, Table 2). We projected the intergroup difference maps of CBF, DC, and CBF/DC ratios onto an overlay map to represent more intuitively the cause of the changes in the CBF/DC ratio (Figure 2b). The results showed a significant negative correlation (r = −0.408, P = 0.038) between the increased CBF/DC ratio in the right MFG and the performance intelligence quotient scores of Wechsler Intelligence Scale.Conclusion

Children with IGE present reduced global CBF-DC coupling, indicating neurovascular decoupling. Furthermore, the regional disrupted CBF-DC coupling is associated with executive and cognitive dysfunction. These findings provide new neuroimaging evidence of neurovascular decoupling in children with IGE and may be helpful for a deeper understanding of the potential neuropathological mechanisms in seizure generation, providing new biomarkers of cognitive performance in childhood IGE.Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of their research group for useful discussions.References

1. Guerrini R. Epilepsy in children. Lancet (London, England). Feb 11 2006;367(9509):499-524. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68182-8

2. Braun KP. Preventing cognitive impairment in children with epilepsy. Current opinion in neurology. Apr 2017;30(2):140-147. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000424

3. Bertini G, Bramanti P, Constantin G, et al. New players in the neurovascular unit: insights from experimental and clinical epilepsy. Neurochem Int. Dec 2013;63(7):652-9. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2013.08.001

4. Presta I, Vismara M, Novellino F, et al. Innate Immunity Cells and the Neurovascular Unit. Int J Mol Sci. Dec 3 2018;19(12)doi:10.3390/ijms19123856

5. Patel DC, Tewari BP, Chaunsali L, Sontheimer H. Neuron-glia interactions in the pathophysiology of epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurosci. May 2019;20(5):282-297. doi:10.1038/s41583-019-0126-4

6. Prager O, Kamintsky L, Hasam-Henderson LA, et al. Seizure-induced microvascular injury is associated with impaired neurovascular coupling and blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Epilepsia. Feb 2019;60(2):322-336. doi:10.1111/epi.14631

Figures