0046

Detecting individual variation in white matter microstructure in a high-risk infant population using deep normative modelling1Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, 2Victorian Infant Brain Studies (VIBeS), Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia, 3Developmental Imaging, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia, 4Neurosurgery Advanced Clinical Imaging Service (NACIS), Department of Neurosurgery, The Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, 5Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 6The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, 7Neonatal Medicine, The Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, 8Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Neonatal, Neuro

There is large inter-individual variation in cognitive outcomes of adults born preterm, which may relate to under-recognised heterogeneity in white matter tract microstructural disturbances. This study created a normative model of white matter tract profiles using deep learning in term-born adults (n=95). The model was then applied to detect anomalies in tract profiles of preterm adults (n=111). The location and extent of anomalies varied across preterm adults. Further, tract anomalies were correlated with neonatal brain injury and IQ. Thus, this study demonstrates inter-individual variation in white matter abnormalities in preterm adults, helping to explain variation in cognitive outcomes.Introduction

Children born preterm exhibit cognitive difficulties which persist into adulthood and negatively affect academic performance, social interactions and mental health[1]. There is large inter-individual variation in cognitive outcomes of these children, the basis of which is still not understood[2]. One contributing factor may be unrecognised variation in brain white matter developmental patterns and disturbances. Prior diffusion MRI analyses demonstrated group-level white matter microstructural alterations in adults born preterm[3,4], but there is a need for individualised, single-subject approaches. We aimed to create models of normative white matter tract microstructural profiles in term-born adults, and use the models to investigate variation in microstructural profiles of young adults born preterm.Methods

This population-based study involved 111 infants born preterm (extremely preterm, i.e., <28 weeks) and 95 term-born control infants, who underwent MRI (3T scanner) when they reached young adulthood (age 18 years) and had usable T1-weighted and diffusion-weighted images (b=3000s/mm2, 45 directions).Diffusion data were corrected for Gibbs-ringing[5], susceptibility distortion artefact[6,7], and motion artefact[8,9]. Automated white matter tract segmentation was performed using TractSeg[10] based on fibre orientation distributions obtained from constrained spherical deconvolution[11]. Tract profiling was performed on 29 major fibre bundles, whereby fibre density (FD)[12], tissue microstructural and free-water composition metrics (TW, TG, TC)[13-16] and diffusion tensor metrics (FA, MD) were sampled at 20 segments along the tracts[17].

To firstly demonstrate baseline group-level differences, tract profiles were compared between preterm and control groups using linear regressions adjusted for age and sex. Then, along-tract profiles of all bundles were concatenated to form feature vectors (one vector for each of the 6 microstructural metrics) and entered into a deep autoencoder model[18]. The model was trained to reconstruct tract profiles using data from control participants, thereby learning a representation of normative tract microstructural patterns. Model validation was performed using five-fold cross-validation, by training on 80% of controls, and testing on 20% of controls and a matched number of preterm participants, repeated over 100 iterations. Feature normalisation and age and sex regression were performed on the training set and applied to the test set. Model performance was assessed by the ability of the model to classify control and preterm groups, using the area under curve (AUC). The difference between reconstructed and input tract profiles (mean absolute error) was calculated for all participants to obtain an anomaly score, representing the extent to which an individual deviated from learned normative profiles. Anomaly scores were compared between groups, and correlated with clinical variables, using linear regressions. Leave-one-out cross-validation determined which tract segments exhibited anomalies in individuals.

Results

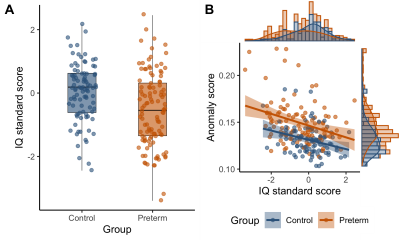

At a group level, young adults born preterm exhibited lower microstructural density and higher free-water content across substantial portions of most tracts compared with controls (Fig 1).The discriminating power of the deep normative model based on each microstructural metric is shown in Fig 2A. Anomaly scores derived from the model were higher in the preterm than control group (Fig 2B). Variance in anomaly scores was higher in the preterm than control group (all p<0.001). Anomalies were distributed across many tracts in young adults born preterm, with high anomaly rates seen in periventricular and non-periventricular tracts, including the corpus callosum, optic radiation, and inferior and superior longitudinal fasciculus (Fig 2C).

Lower gestational age at birth and neonatal brain injury diagnosed from cranial ultrasound were related to higher anomaly scores. More specifically, young adults born preterm with a history of intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) grade 3 or cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) exhibited higher anomaly scores than young adults born preterm with IVH grade 0, 1 or 2. Birth weight, small for gestational age birth, sex and lung injury were not related to anomaly scores (Fig 3).

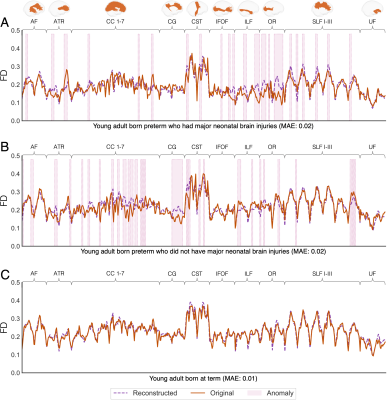

In Fig 4A, an anomaly profile is presented for an individual born preterm who was previously diagnosed with bilateral IVH grade 3 and who demonstrated large anomaly scores. Microstructural deviations were observed along several tracts in this individual, particularly posterior periventricular tracts (optic radiation and inferior longitudinal fasciculus). Alternatively, Fig 4B presents the anomaly profile for an individual born preterm who had no neonatal brain injuries, but who also had large anomaly scores. Microstructural deviations were present in several tracts for this individual; most prominently the cingulum. The pattern of anomalies differed between individuals.

Higher anomaly scores were related to lower IQ scores assessed concurrently (Fig 5).

Discussion

We presented a deep normative model based on tract microstructural characteristics, which had good power for discriminating between preterm and control groups, with comparable AUCs to those previously reported for other populations[18]. This shows the model was able to learn normative tract characteristics and detect deviations in the preterm group. Analysis of the anomaly scores and individual profiles demonstrated substantial variation in anomalies between individuals born preterm. Anomalies were more likely to be detected in individuals who had neonatal brain injuries, but were also detected in individuals without neonatal brain injuries, suggesting the model may detect anomalies that may not otherwise be visible. Anomalies were related to cognitive outcomes, highlighting their potential clinical relevance.Conclusion

This study demonstrated inter-individual variation in white matter abnormalities in a high-risk preterm population and identified individuals with substantial white matter abnormalities, helping to explain variation in clinical outcomes.Acknowledgements

This work is presented on behalf of members of the Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. We thank Maxime Chamberland for analysis support, The Medical Imaging staff at The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne for their assistance and expertise in the collection of MRI data included in this study, and the participants and families for their willingness to participate in this study. This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship, and a Monash Graduate Excellence Scholarship, Monash University. Parts of this work were conducted within the Developmental Imaging research group, supported by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Department of Paediatrics at The University of Melbourne and the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Funding organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the abstract.References

[1] Cheong JLY, Haikerwal A, Anderson PJ, et al. Outcomes into adulthood of infants born extremely preterm. Seminars in Perinatology. 2021;45(8):151483.

[2] Anderson PJ, Cheong JLY, Thompson DK. The predictive validity of neonatal MRI for neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm children. Seminars in Perinatology. 2015;39(2):147-158.

[3] Menegaux A, Hedderich DM, Bäuml JG, et al. Reduced apparent fiber density in the white matter of premature-born adults. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):17214.

[4] Irzan H, Molteni E, Hutel M, et al. White matter analysis of the extremely preterm born adult brain. Neuroimage. 2021;237:118112.

[5] Kellner E, Dhital B, Kiselev VG, et al. Gibbs-ringing artifact removal based on local subvoxel-shifts. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;76(5):1574-1581.

[6] Schilling KG, Blaber J, Hansen C, et al. Distortion correction of diffusion weighted MRI without reverse phase-encoding scans or field-maps. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0236418.

[7] Schilling KG, Blaber J, Huo Y, et al. Synthesized b0 for diffusion distortion correction (Synb0-DisCo). Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2019;64:62-70.

[8] Andersson JLR, Graham MS, Zsoldos E, et al. Incorporating outlier detection and replacement into a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction of diffusion MR images. NeuroImage. 2016;141:556-572.

[9] Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. NeuroImage. 2016;125:1063-1078.

[10] Wasserthal J, Neher P, Maier-Hein KH. TractSeg - Fast and accurate white matter tract segmentation. NeuroImage. 2018;183:239-253.

[11] Dhollander T, Connelly A. A novel iterative approach to reap the benefits of multi-tissue CSD from just single-shell (+b=0) diffusion MRI data. 24th Proceedings of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016, 3010.

[12] Raffelt D, Tournier JD, Rose S, et al. Apparent Fibre Density: A novel measure for the analysis of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance images. NeuroImage. 2012;59(4):3976-3994.

[13] Kelly C, Dhollander T, Harding IH, et al. Brain tissue microstructural and free-water composition 13 years after very preterm birth. NeuroImage. 2022;https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119168:119168.

[14] Khan W, Egorova N, Khlif MS, et al. Three-tissue compositional analysis reveals in-vivo microstructural heterogeneity of white matter hyperintensities following stroke. NeuroImage. 2020;218:116869.

[15] Khan W, Khlif MS, Mito R, et al. Investigating the microstructural properties of normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) preceding conversion to white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) in stroke survivors. NeuroImage. 2021;232:117839.

[16] Mito R, Dhollander T, Xia Y, et al. In vivo microstructural heterogeneity of white matter lesions in healthy elderly and Alzheimer's disease participants using tissue compositional analysis of diffusion MRI data. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2020;28:102479.

[17] Chandio BQ, Risacher SL, Pestilli F, et al. Bundle analytics, a computational framework for investigating the shapes and profiles of brain pathways across populations. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):17149.

[18] Chamberland M, Genc S, Tax CMW, et al. Detecting microstructural deviations in individuals with deep diffusion MRI tractometry. Nature Computational Science. 2021;1(9):598-606.

Figures