0044

Causal evidence for cerebello-limbic-striatal circuit dynamics supporting depression1MRI, the first affiliated hospital of zhengzhou university, zhengzhou, henan, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Adolescents, Neuroscience, Resting-state functional connectivity

The striatum is known to be impaired in MDD patients. Abnormal structure or function of the striatum may disturb the top-down regulation of negative emotions among persons more vulnerable to developing depressive state, especially adolescent. Here, we investigated (1) voxel-wise FC between the striatal nucleus and the whole brain; (2) region of interest wise effective connectivity using DCM analysis, according to the between-group differences in FC of the striatal nucleus. We found decreased FC in cerebello-limbic-striatal circuit, and further DCM analysis showed the dysregulation of vrPUT nucleus disturb the top-down regulation of cerebello-limbic-striatal circuit during reward processing in adolescent MDD.Background or Purpose

Striatum-based circuits have been implicated in major depressive disorder (MDD), a disease that reflects deficits of reward processing [1]. Abnormal structure or function of the striatum may disturb the top-down regulation of negative emotions among persons more vulnerable to developing depressive state [2], especially adolescent. Although, most existing rsFC studies of MDD can identify altered connections between brain regions, rsFC does not indicate causal influence (directed connectivity) among the neural populations that give rise to the regional resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) signals [3]. Dynamic causal modeling (DCM) can characterize the causal relationships and information flow between brain regions based on rsFC, and has become a predominant method by which to quantify effective connectivity (EC) [4]. Although previous studies have provided evidence indicative of an abnormal communication of the striatum in the case of MDD, it is still unclear which specific striatal nucleus is the core structure underlying MDD. And striatum has commonly been studied as a whole structure when investigating altered rsFC in MDD [5,6,7]. However, recent neuroimaging studies indicate that there is a striatal functional topography, and this information is missed when using as a whole structure [8].Methods

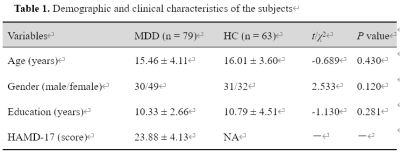

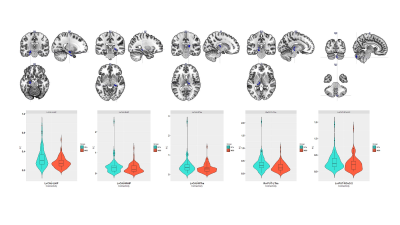

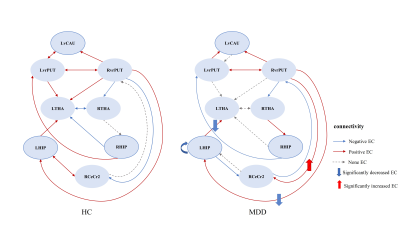

A total of 79 first-episode, drug-naïve adolescents with MDD and 63 matched healthy controls (HCs) (Table 1), underwent resting-state functional MRI scans. Based on previous research [9], the striatum can be subdivided into six bilateral striatal seeds: nucleus accumbens (NAcc), ventral caudate (vCAU), dorsal caudate (dCAU), dorsal caudal putamen (dcPUT), dorsal rostral putamen (drPUT) and ventral rostral putamen (vrPUT). Resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) of the striatal nucleus were investigated between the striatal nucleus and the whole brain. According to the between-group differences in rsFC of the striatal nucleus, we selected eight areas as ROIs, including the left vCAU, bilateral vrPUT, bilateral HIP, bilateral thalamus (THA) and right cerebellum crus II (CeCr2). After extracting the time series from all eight ROIs, a fully-connected model which has bi-directional connections between any pair of ROIs was specified for each subject, which resulted in 64 connections, including the self-connections of each node (Figure 2). We were modeling on the rs-fMRI data. No exogenous input was included in the model. We only report connection coefficients with a posterior probability > 0.95. The connection coefficients for each group were assessed using one-sample Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank test and compared with the value 0, whereby an index value of significantly < 0 indicates negative EC and an index value of significantly > 0 indicates positive EC. To investigate the relationship between altered connectivity and symptom severity, significant rsFC and EC were correlated with clinical measures in the MDD and HC groups. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni method (P < 0.05/50 = 0.001).Results

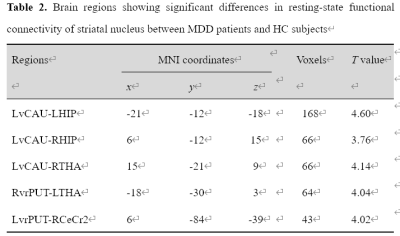

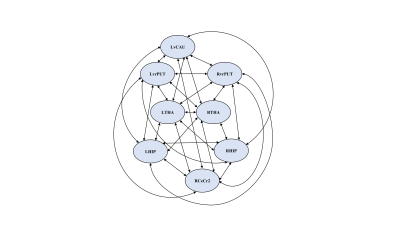

Adolescents with MDD manifested decreased rsFC of the left ventral caudate (vCAU)-bilateral hippocampus (HIP), the right ventral rostral putamen (vrPUT)-left thalamus (THA), the left vCAU-right THA, as well as decreased rsFC of the left vrPUT-right cerebellum crus II (CeCr2) (Figure 1; Table 2). We found some significant correlations between above connections in each group and across all participants. In the single-group analysis (one-sample Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank test), we found some significant positive/negative EC for each group and the self-connection of each node. In general, the MDD group indicated decreased correlations between connections. Compared with HCs, DCM showed significantly stronger EC from the right vrPUT nucleus to the right CeCr2 and the weaker EC from the right vrPUT nucleus to the left HIP and then from the left HIP to the left THA, as well as the enhanced self-inhibition of the left HIP in MDD group compared with the HCs (Figure 3).No significant rsFC or EC were correlated with HAMD scores in MDD group after Bonferroni corrected (P < 0.05/50 = 0.001).Conclusions

Our study indicates that the key structure in the striatum underlying MDD mainly located in the vrPUT nucleus, and the dysregulation of vrPUT nucleus disturbs the top-down regulation of cerebello-limbic-striatal circuit during reward processing in adolescent MDD. Our study provides direct evidence that the cerebello-limbic-striatal circuit is associated with MDD.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.81601467, 81871327, 81601472); Medical science and technology research project of Henan province (201701011).References

[1] Stringaris, A., Vidal-Ribas Belil, P., Artiges, E., Lemaitre, H., Gollier-Briant, F., Wolke, S., Vulser, H., Miranda, R., Penttilä, J., Struve, M., Fadai, T., Kappel, V., Grimmer, Y., Goodman, R., Poustka, L., Conrod, P., Cattrell, A., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A.L., Bromberg, U., Büchel, C., Flor, H., Frouin, V., Gallinat, J., Garavan, H., Gowland, P., Heinz, A., Ittermann, B., Nees, F., Papadopoulos, D., Paus, T., Smolka, M.N., Walter, H., Whelan, R., Martinot, J.L., Schumann, G., Paillère-Martinot, M.L., 2015. The Brain's Response to Reward Anticipation and Depression in Adolescence: Dimensionality, Specificity, and Longitudinal Predictions in a Community-Based Sample. Am J Psychiatry 172(12), 1215-1223.

[2] Fischer, A.S., Ellwood-Lowe, M.E., Colich, N.L., Cichocki, A., Ho, T.C., Gotlib, I.H., 2019. Reward-circuit biomarkers of risk and resilience in adolescent depression. J Affect Disord 246, 902-909.

[3] Friston, K.J., 2011. Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connect 1(1), 13-36.

[4] Friston, K.J., Harrison, L., Penny, W., 2003. Dynamic causal modelling. Neuroimage 19(4), 1273-1302.

[5] He, Z., Sheng, W., Lu, F., Long, Z., Han, S., Pang, Y., Chen, Y., Luo, W., Yu, Y., Nan, X., Cui, Q., Chen, H., 2019. Altered resting-state cerebral blood flow and functional connectivity of striatum in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 90, 177-185.

[6] Forbes, E.E., Dahl, R.E., 2012. Research Review: altered reward function in adolescent depression: what, when and how? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(1), 3-15. Forbes, E.E., Hariri, A.R., Martin, S.L., Silk, J.S., Moyles, D.L., Fisher, P.M., Brown, S.M., Ryan, N.D., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D.A., Dahl, R.E., 2009. [7] Altered striatal activation predicting real-world positive affect in adolescent major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 166(1), 64-73.

[8] Fan, J., Liu, W., Xia, J., Li, S., Gao, F., Zhu, J., Han, Y., Zhou, H., Liao, H., Yi, J., Tan, C., Zhu, X., 2021. Childhood trauma is associated with elevated anhedonia and altered core reward circuitry in major depression patients and controls. Hum Brain Mapp 42(2), 286-297.

[9] Di Martino, A., Scheres, A., Margulies, D.S., Kelly, A.M., Uddin, L.Q., Shehzad, Z., Biswal, B., Walters, J.R., Castellanos, F.X., Milham, M.P., 2008. Functional connectivity of human striatum: a resting state FMRI study. Cereb Cortex 18(12), 2735-2747.

Figures

Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; HCs, healthy control subjects; LvCAU, left ventral caudate; LHIP, left hippocampus; RHIP, right hippocampus; RvrPUT, right ventral rostral putamen; LvrPUT, left ventral rostral putamen; RCeCr2, right cerebellum crus II; LTHA, left thalamus; RTHA, right thalamus.

Abbreviations: LvCAU, left ventral caudate; LHIP, left hippocampus; RHIP, right hippocampus; RvrPUT, right ventral rostral putamen; LvrPUT, left ventral rostral putamen; RCeCr2, right cerebellum crus II; LTHA, left thalamus; RTHA, right thalamus.

Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; HCs, healthy control subjects; EC, effective connectivity; LvCAU, left ventral caudate; LHIP, left hippocampus; RHIP, right hippocampus; RvrPUT, right ventral rostral putamen; LvrPUT, left ventral rostral putamen; RCeCr2, right cerebellum crus II; LTHA, left thalamus; RTHA, right thalamus.