0043

Structural reorganisation in higher-order brain networks of the common marmoset from infancy to adulthood revealed by DTI tractography1Translational Neuroimaging Laboratory; Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Brain Connectivity

Adolescence is a critical period in development where neuropsychiatric symptoms emerge. The most striking morphological changes in the brain throughout this time are seen in white matter. Here we present a large longitudinal non-human primate study mapping detailed changes in the structural DTI connectome from infancy to adulthood, showing changes in connectivity across this period in higher order association areas, particularly in prefrontal cortex. We demonstrate integration of subcortical structures across hemispheres in the adult brain alongside differentiation of right and left prefrontal areas in their community structure.Introduction

The emergence of neuropsychiatric disorders during development [1] suggests early adolescence as a critical period of vulnerability, but there is limited understanding of the changes in brain circuits over this period, or the mechanisms behind their dysfunction that can lead to disease. Animal models are a crucial part of addressing this problem, and here we assess white matter connectivity changes from infancy to adulthood in a new world primate, the common marmoset. We apply graph theory with deterministic tractography in an in vivo, mixed cross-sectional, longitudinal study to map key changes in structural brain networks from infancy to adulthood.Methods

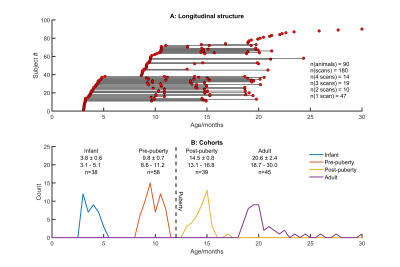

Imaging 180 scans from 90 animals (see Figure 1) were acquired at 9.4T (Bruker BioSpec 94/20) with an 8ch array receiver coil (RAPID Biomedical). Marmosets were anaesthetised with isoflurane (1-2% in 0.4 l/min O2). For DTI, an EPI respiratory-gated multi-shell Stejskal-Tanner sequence was used (64 slices 333µm thickness and in-plane resolution, b-values 600/900 s/mm2 60 directions and 5 B0 images).Processing Before DTI reconstruction, images were coregistered to correct for eddy-currents[2]. Deterministic fibre tracking was performed with DSIStudio [3] (whole-brain seeding, step size 0.1mm, max turning angle 65°, 3.5×106 fibres). Connectivity matrices were produced from brain parcellations (303 cortical and subcortical regions following [4]) and cross-validated against histological tract-tracing data [5]. Graph theory metrics were calculated from weighted matrices thresholded at 20% sparsity and assessed using BCT [6]. Network measures were assessed longitudinally using linear mixed effects modelling subject as a random effect, p-values refer to t-tests for zero coefficients unless otherwise stated [8]

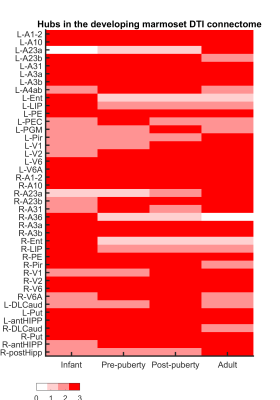

Hubs Hubs were identified at each group by scoring nodes equally for being in the top 20% of degree, betweenness centrality, clustering coefficient and nodal efficiency.

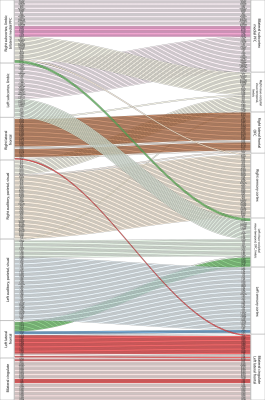

Modular structure Modules were assigned with the tuned Louvain algorithm [6]. Significance was determined using non-parametric testing following [9].

Results and Discussion

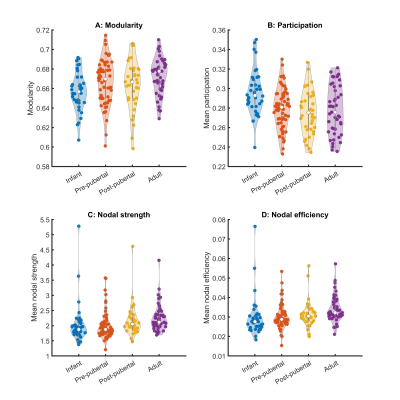

Key network metrics are shown in Figure 2. Modularity increases with age (p < 0.003), consistent with the decrease in nodal participation (p < 0.0007). Connections with neighbouring nodes became stronger, reflected by increases in nodal strength (p=0.03) and local nodal efficiency (p<0.01). Mean clustering coefficient increases (p < 0.006), but global network efficiency and characteristic path length did not change with age (p=0.07, p=0.19, respectively).Hubs of the adult brain network were largely symmetric, comprising primary sensory, motor and visual cortices (Figure 3). Posterior cingulate cortex (particularly A23a) scored higher in adults than in younger animals. Other hubs included parts of the hippocampus and basal ganglia. Hub scores for entorhinal cortex decreased bilaterally from infancy to puberty.

Modular development from infancy to adulthood is shown in Figure 4. This reveals hemispheric integration of the subcortical structures across development, consistent with previous studies in the marmoset which found that adulthood was characterised by increased structural covariance between hemispheres [4]. Focussing on frontal lobes, we found differentiation between left and right lateral- and orbito-frontal areas. Lateral frontal areas in the left hemisphere became more closely associated with bilateral cingulate cortex, whereas those on the right became associated with orbitofrontal regions. In contrast, bilateral medial prefrontal cortex became fully integrated with subcortical emotional and motivational circuits, bilaterally.

Conclusion

Here we present the most detailed non-human primate DTI connectome analysis in a longitudinal study from infancy to adulthood performed to date. Increases in modularity track the specialisation of brain circuits through development. Intriguingly, this measure slows across puberty, in common with volume growth trajectories measured over this period [4]. We found changes in community structure and network properties that occur both prior to and following puberty, including substantial structural reorganisation seen in the frontal cortex. Understanding the timing of these changes is crucial in designing experiments to explore how environmental perturbations can disrupt the successful formation of frontal circuits implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders.Acknowledgements

This work was funded by MRC (MR/M023990/1 to ACR) and Wellcome Trust (108089/Z/15/Z to ACR)References

[1] Kessler RC et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593-602.

[2] SPM12, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Neuroimaging, UCL

[3] DSIStudio Yeh, Fang-Cheng, et al. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. (2013): e80713. PLoS ONE 8(11): e80713. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080713

[4] Quah et al. 2022 Higher-order brain regions show shifts in structural covariance in adolescent marmosets. Cerebral Cortex 2022, 32(18):4128-4140

[5] www.marmosetbrain.org Marmoset Brain Connectivity Atlas

[6] Brain Connectivity Toolbox; Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. Rubinov M, Sporns O (2010) NeuroImage 52:1059-69.

[8] Matlab 2021, Mathworks Inc. Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox.

[9] Alexander-Bloch A et al. The discovery of population differences in network community structure: New methods and applications to brain functional networks in schizophrenia Neuroimage. 2012 Feb 15; 59(4): 3889–3900.

Figures