0039

Total and regional brain volumes in fetuses with congenital heart disease

Daniel Cromb1,2, Alena Uus1,2, Milou Van Poppel3, Johannes Steinweg3, Alexandra Bonthrone1,2, Alessandra Maggioni1, Paul Cawley1,4, Vanessa Kyriakopoulou1, Jacqueline Matthew1, Anthony Price1,2, A David Edwards1,2, Maria Deprez1,2, Joseph V Hajnal1,2, David F Lloyd1,3,5, Kuberan Pushparajah1,3,5, John Simpson1,3,5, Mary Rutherford1,4, and Serena J Counsell1,2

1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Cardiovascular Imaging, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Science, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 4MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Paediatric Cardiology, Evelina London Children's Hospital, London, United Kingdom

1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Cardiovascular Imaging, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Science, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 4MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Paediatric Cardiology, Evelina London Children's Hospital, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Fetal, Brain, Brain Volumes, Congenital Heart Disease

Total and regional brain volumes, derived from automatically segmented, motion-corrected, 3D fetal brain MR images were obtained in 45 healthy fetuses and 305 fetuses with isolated congenital heart disease (CHD) in the third trimester. Total brain tissue, cortical and deep grey matter, and white matter volumes are significantly lower in fetuses with CHD where cerebral oxygenation and substrate delivery are likely to be reduced. Brain volumes appear normal in fetuses with CHD but an otherwise expected normal cerebral oxygenation.Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is common, affecting ~1% of live-births [1], and is associated with developmental impairments persisting into adulthood [2–4]. Exact mechanisms behind these impairments remain unclear but are likely to be multifactorial.There is evidence that fetuses with CHD have impaired brain growth [5–10]. However, these studies are limited by small cohort sizes, or focus on specific diagnoses rather than underlying physiology. Furthermore, little work has been done involving CHD classed as ‘mild’. Receiving a CHD diagnosis of any kind is a source of parental anxiety, so investigating how less severe types of CHD impact brain development is warranted.

Fetal CHD can be grouped into three broad categories, as previously described [11–14]: (1) Normal expected cerebral oxygenation; (2) Mild-to-Moderately reduced cerebral oxygenation; (3) Severely reduced cerebral oxygenation.

We aimed to explore how expected cerebral oxygenation affects brain volumes in a large cohort of fetuses with CHD.

Methods

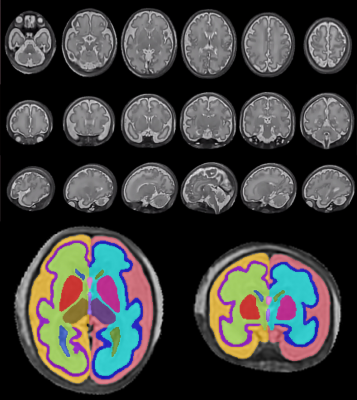

Women referred to our fetal cardiology service with a confirmed fetal diagnosis of CHD between 2014-2022, or women experiencing a low-risk pregnancy recruited to the iFIND project (https://www.ifindproject.com/) were included. Written, informed consent was obtained before MRI (NHS REC: 07/H0707/105&14/LO/1806). Twins, fetuses with confirmed genetic abnormalities, or with extracardiac or structural brain anomalies were excluded.Images were acquired on a Philips Ingenia 1.5T MRI scanner. Fetal brain images were acquired using a T2-weighted single-shot fast-spin-echo sequence (TR=1500ms,TE=80ms,in-plane resolution=1.25mm2,slice thickness=2.5mm,slice gap=-1.25mm), optimised for fetal imaging [15]. Images were motion-corrected and reconstructed using an advanced slice-to-volume reconstruction (SVR) technique [16,17], before being up-sampled to 0.5mm3 isotropic resolution. Each SVR was independently assessed by two clinicians using a previously published scoring system [18]. Poor quality datasets were excluded (Figure 1).

Each brain SVR was segmented using an automated tool based on the developing Human Connectome Project segmentation protocol with 19 label ROIs (https://gin.g-node.org/kcl_cdb/fetal_brain_mri_atlas) and a 3D-UNet [19] convolutional neural network having undergone semi-supervised training in MONAI [20] (Figure 1). All segmentations were reviewed and confirmed to be acceptable for volumetry. Volumes were generated for cortical grey matter (cGM), white matter (WM), deep grey matter (dGM), cerebellum, brainstem, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and total brain tissue volume (TTV), calculated by summing cGM, WM, dGM, cerebellum and brainstem (Figure 2).

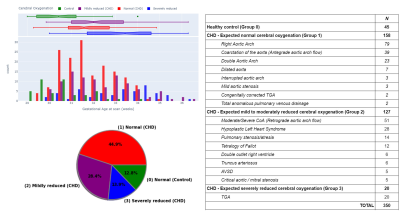

Each fetus with CHD was categorised into one of three groups, as described above, informed by the primary underlying CHD diagnosis and fetal echocardiographic and cardiac MR findings. Healthy control fetuses were assigned group (0).

An ANCOVA was performed to explore any effect of expected cerebral oxygenation on brain volumes, accounting for fetal sex and gestational age (GA) at scan. P-values, corrected for multiple-testing (pFDR) are reported.

Results

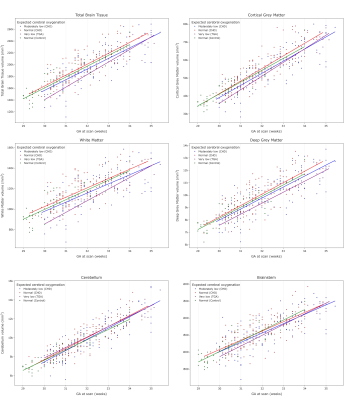

Data from 350 fetuses were included: 45 healthy controls and 305 with CHD (158 in group 1, 127 in group 2, 20 in group 3). There was a significant difference in GA at scan between groups (pFDR<0.001), but not fetal sex (p=0.96). Histograms showing the distribution of GA at scan and CHD groups are in Figure 3.After accounting for sex and scan GA, there was a significant difference in TTV, cGM, WM and dGM volumes (all pFDR<0.004) between groups (Figure 4).

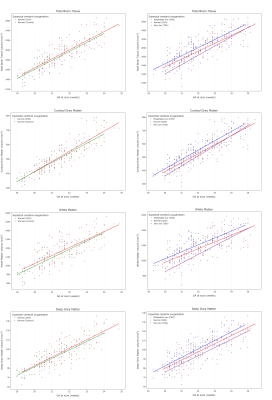

A post-hoc analysis comparing total and regional brain volumes between control fetuses and only CHD fetuses with expected normal cerebral oxygenation was performed. After accounting for sex and scan GA, no significant group difference was seen in any regions (pFDR>0.19). A further post-hoc analysis comparing brain volumes between only fetuses with CHD (Groups 1-3) was performed. After accounting for sex and scan GA, a significant difference in TTV, cGM, WM and dGM (pFDR<0.002 for all) between groups was identified (Figure 5).

Discussion

This is one of the largest studies to date exploring brain volumes in fetuses with CHD. Expected cerebral oxygenation is significantly associated with total and regional brain volumes, with likely reduced cerebral oxygenation correlating with smaller volumes. Brain volumes in fetuses with TGA are most affected. WM appears to be the most strongly impacted region. This classification approach, based on expected cerebral oxygenation, is supported by recent advances allowing in-utero quantification of fetal arterial and venous oxygen saturations [12,21–23].To our knowledge, this is the first large study exploring brain volumes in fetuses with mild CHD (i.e. associated with normal cerebral oxygenation). We identified no significant difference in brain volumes between these fetuses and healthy controls, supporting the hypothesis that cerebral oxygenation is a key mediator of fetal brain growth.

Our results align with existing studies that identify fetuses with TGA as having the smallest brain volumes [5], and in that dGM volumes are smaller in fetuses with severely reduced cerebral oxygenation [24]. They also complement work exploring associations between reduced cerebral oxygen delivery and brain volumes at earlier gestations [7,8] .

We focussed on a narrow GA range, as this is when most clinical fetal cardiac MRI’s are performed. We assumed linear trends in brain growth across gestation, which is not necessarily the case [24] but is appropriate for the narrow GA window used here. Future work should use direct measurements of fetal cerebral oxygenation where available, and investigate how brain volumes correlate with later neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the families who participated in this research. We also thank our research radiologists; our research radiographers, and our fetal scanning team. In addition, we thank the staff from the Evelina London Children’s Hospital Fetal and Paediatric Cardiology Departments and the Centre for the Developing Brain at King’s College London.This research was funded by the Medical Research Council UK (MR/L011530/1; MR/V002465/1). This research was supported by by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z], the Wellcome Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Centre for Medical Engineering at King's College London (WT 203148/Z/16/Z) and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

1. EUROCAT. European Platform on Rare Disease Registration. 2020.2. Ilardi D, Ono KE, McCartney R et al. Neurocognitive functioning in adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:166–73.

3. Klouda L, Franklin WJ, Saraf A et al. Neurocognitive and executive functioning in adult survivors of congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:91–8.

4. Rodriguez CP, Clay E, Jakkam R et al. Cognitive impairment in adult CHD survivors: A pilot study. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis 2021;6:100290.

5. Jørgensen DES, Tabor A, Rode L et al. Longitudinal Brain and Body Growth in Fetuses With and Without Transposition of the Great Arteries. Circulation 2018;138:1368–70.

6. Paladini D, Finarelli A, Donarini G et al. Frontal lobe growth is impaired in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:776–82.

7. Ren J-Y, Zhu M, Dong S-Z. Three-Dimensional Volumetric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Detects Early Alterations of the Brain Growth in Fetuses With Congenital Heart Disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2021;54:263–72.

8. Rollins CK, Ortinau CM, Stopp C et al. Regional brain growth trajectories in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ann Neurol 2021;89:143–57.

9. Wu Y, Lu Y-C, Kapse K et al. In Utero MRI Identifies Impaired Second Trimester Subplate Growth in Fetuses with Congenital Heart Disease. Cereb Cortex 2021:bhab386.

10. Dovjak GO, Hausmaninger G, Zalewski T et al. Brainstem and cerebellar volumes at magnetic resonance imaging are smaller in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022, DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.03.030.

11. Donofrio MT, Bremer YA, Schieken RM et al. Autoregulation of Cerebral Blood Flow in Fetuses with Congenital Heart Disease: The Brain Sparing Effect. Pediatr Cardiol 2003;24:436–43.

12. Al Nafisi B, van Amerom JF, Forsey J et al. Fetal circulation in left-sided congenital heart disease measured by cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a case–control study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15:65.

13. Sun L, Macgowan CK, Sled JG et al. Reduced Fetal Cerebral Oxygen Consumption is Associated With Smaller Brain Size in Fetuses With Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation 2015;131:1313–23.

14. Mebius MJ, Clur SAB, Vink AS et al. Growth patterns and cerebroplacental hemodynamics in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53:769–78.

15. Lloyd DFA, van Poppel MPM, Pushparajah K et al. Analysis of 3-Dimensional Arch Anatomy, Vascular Flow, and Postnatal Outcome in Cases of Suspected Coarctation of the Aorta Using Fetal Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;14:e012411.

16. Kuklisova-Murgasova M, Quaghebeur G, Rutherford MA et al. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med Image Anal 2012;16:1550–64.

17. Uus A, Grigorescu I, van Poppel M et al. 3D UNet with GAN Discriminator for Robust Localisation of the Fetal Brain and Trunk in MRI with Partial Coverage of the Fetal Body. Bioengineering, 2021.

18. Uus AU, Egloff Collado A, Roberts TA et al. Retrospective motion correction in foetal MRI for clinical applications: existing methods, applications and integration into clinical practice. Br J Radiol 2022:20220071.

19. Çiçek Ö, Abdulkadir A, Lienkamp SS et al. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In: Ourselin S, Joskowicz L, Sabuncu MR, et al. (eds.). Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2016. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016, 424–32.

20. MONAI Consortium. MONAI: Medical Open Network for AI. 2022.

21. Peyvandi S, Donofrio MT. Circulatory Changes and Cerebral Blood Flow and Oxygenation During Transition in Newborns With Congenital Heart Disease. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2018;28:38–47.

22. Roberts TA, van Amerom JFP, Uus A et al. Fetal whole heart blood flow imaging using 4D cine MRI. Nat Commun 2020;11:4992.

23. Saini BS, Darby JRT, Portnoy S et al. Normal human and sheep fetal vessel oxygen saturations by T2 magnetic resonance imaging. J Physiol 2020;598:3259–81.

24. Link D, Braginsky MB, Joskowicz L et al. Automatic Measurement of Fetal Brain Development from Magnetic Resonance Imaging: New Reference Data. Fetal Diagn Ther 2018;43:113–22.

Figures

Figure 1: Example of a good quality 3D fetal brain SVR in coronal, axial and sagittal views. Regional segmentations are shown on selected Axial (Left) and Coronal (Right) slices, acquired in a different fetus. Colours correspond to: CSF (Left - Light red & Right - Orange), cortical grey matter (Left - Dark Blue & Right - Purple), white matter (Left - Light Blue & Right - Light Green), Lateral ventricles (Left - Dark Green & Right - Dark Blue), Lentiform nucleus (Left - Pink & Right - Red), Thalamus (Left - Dark Purple & Right - Light Brown), Cavum Septum Pellucidum - Pink and Third Ventricle - Purple

Figure 2: 3D representations of regional brain segmentations: Top row: Extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid (left - light red & right - orange). Second row: cortical grey matter (left - dark blue & right - purple). Third row: white matter (left - light blue & right - light green). Bottom row: lateral ventricles (left - dark green & right - dark blue), lentiform nucleus (left - pink & right - red), thalamus (left - dark purple & right - light brown), cavum septum pellucidum - pink, third ventricle - purple, cerebellar hemispheres (left - green & right - light purple) and brainstem (blue).

Figure 3: Study population demographics and classification of congenital heart disease (CHD) according to expected cerebral oxygenation for 350 fetuses (179 female, 171 male)

Figure 4: Scatter plots showing total brain tissue and regional brain volumes across gestational age for 350 fetuses grouped according to expected cerebral oxygenation (305 CHD, 45 normal). There is a significant difference in total brain tissue (top left; pFDR=3.2x10-4), cortical grey matter (top right,; pFDR=9.2x10-5), white matter (middle left, pFDR=1.9x10-4) and deep grey matter (middle right, pFDR=0.0029) volumes between groups, after accounting for sex and gestational age at scan, but not cerebellum (bottom left) or brainstem (bottom right).

Figure 5: Scatter plots showing total brain tissue (top row), cortical grey matter (second row), white matter (third row) and deep grey matter (bottom row) volumes across gestational age for: (A - left column) healthy control fetuses (green) and fetuses with CHD but normal cerebral oxygenation (red); and (B - right column) fetuses with CHD and expected normal (red), moderately reduced (purple) or severely reduced (blue) cerebral oxygenation.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0039