0033

Elevated free-water volume in the brains of HIV+ alcohol drinkers compared to HIV- drinkers as an indication of neuro-inflammation1University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States, 2University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, Infectious disease, Alcohol Use

Chronic alcohol use and HIV infection can have synergistic effects that negatively impact the brain leading to abnormalities such as neuro-inflammation. Free-water eliminated DTI (FWE-DTI) has been suggested as a biomarker of neuro-inflammation. This study compare DTI and FWE-DTI derived metrics in the brains of HIV+/HIV- chronic drinkers to determine whether HIV infection or drinking behavior is a more significant factor contributing to brain microstructural abnormalities and neuro-inflammation. Our results suggest that HIV is a more significant factor than drinking level contributing to elevated free water in the brain as a sign of neuro-inflammation.Introduction

Chronic alcohol use is prevalent among people living with HIV (PLWH) and is associated with reduced adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 In addition, alcohol use and HIV infection can have synergistic adverse effects on the brain leading to functional, structural, and metabolic abnormalities.2 In particular, neuro-inflammation has been observed among both PLWH and chronic drinkers. In HIV, this occurs after the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier where it escapes effective targeting by ART.3 In both alcohol use and HIV, translocation of gut bacteria into peripheral tissues triggers pro-inflammatory responses.4 However, these mechanisms are not completely understood, and in-vivo MRI methods such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and free-water eliminated DTI (FWE-DTI)5,6 are increasingly used to investigate neuro-inflammation in alcohol use and HIV infection. FWE-DTI differentiates water contained in the extracellular space from intracellular tissue water trapped within cells, and estimates the extracellular free water volume fraction (FW) which has been suggested as a biomarker of neuro-inflammation.7 In this study, we compare DTI and FWE-DTI derived metrics in the brains of HIV+/HIV- chronic drinkers to determine whether HIV infection or drinking behavior is a more significant factor contributing to brain microstructural abnormalities and neuro-inflammation.Methods

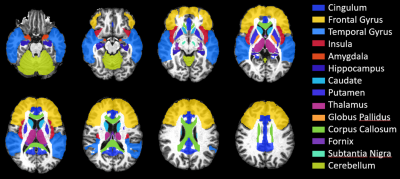

MRI data were collected on a 3T scanner from 25 HIV+ and 18 HIV- chronic drinkers categorized into moderate (male≤14, female≤7 drinks/week) and heavy drinkers (male>14, female>7 drinks/week) as defined by the NIAAA.8 Drinks per week were self-reported from the 30 days prior to scanning. The four groups were: moderate-HIV+ (age: 55.3±4.9, 16M/5F), heavy-HIV+ (age: 55.5±3.9, 1M/3F), moderate-HIV- (age: 56.6±4.3, 11M/3F), heavy-HIV- (age: 54.8±5.7, 2M/2F). The MRI protocol included whole-brain diffusion-weighted (DW) MRI with: b = 1000/2000 s/mm2; 30 gradient directions; TR/TE: 1150/98 ms; voxel dimension: 2.0×2.0×2.0 mm; 54 axial slices. Two additional b0 images were collected using opposite phase encoding direction (AP-PA) with the same parameters.DW-images were pre-processed with FSL9 for susceptibility-induced distortions, eddy currents and motion correction. Tensor fitting was performed using Dipy10 from which we obtained DTI metrics: fractional anisotropy (FA), mean-, axial-, and radial-diffusivities (MD, AD, RD); and FWE-DTI metrics: FWE-FA, FWE-MD, FWE-AD, FWE-RD, and FW. We evaluated these metrics at 14 regions of interest (ROI) relevant to both HIV and alcohol use11,12 selected from the JHU-MNI-SS-type2 atlas13 (figure 1). Large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping (LDDMM)14 was used to inverse transform the atlas in template space to subject space and obtain data for analyses from ROIs in individual subject space.

Statistical analysis was performed using R. ROI-based group comparisons were performed using a two-way ANCOVA analysis to examine the effects of HIV infection and drinking level on each DTI/FWE-DTI metric, controlling for age (significance at p<0.05 adjusted for multiple comparisons with FDR). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were used to determine between-group differences.

Results

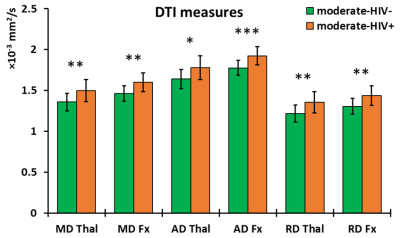

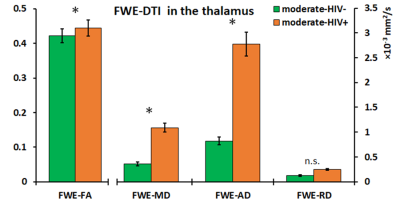

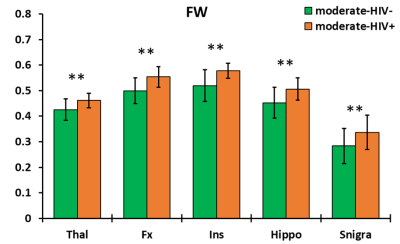

The ANCOVA output showed no significant two-way interaction between HIV infection and drinking level for any metric. Additionally, only HIV infection as a grouping variable had significant effects on imaging outcomes. For DTI metrics, no significant group differences were found in FA, while significantly higher MD, AD, and RD was observed in the moderate-HIV+ group compared to moderate-HIV- group at the thalamus and fornix (figure 2). FWE metrics showed increases in FWE-FA, FWE-MD, and FWE-AD for moderate-HIV+ compared to moderate-HIV- in the thalamus (figure 3). FW was the most significantly different measure with elevated free-water in the thalamus, fornix, insula, hippocampus, and substantia nigra for moderate-HIV+ compared to moderate-HIV- (figure 4).Discussion

Results show widespread FW increase in the brain among HIV+ compared to HIV- drinkers, suggesting multi-regional inflammation due to HIV infection. The thalamus and fornix appear to be the most heavily affected ROIs where we also observed increases in MD, AD, and RD for HIV+ drinkers. This is mirrored by increased thalamic FWE-FA, FWE-MD, and FWE-AD, with no change in FWE-RD, indicating that the higher diffusivity can be attributed to the expansion of the extra-cellular space from inflammation. The thalamus is considered a juction region, where white matter tracts involved in cognitive networks affected by alcohol use traverse through,12 as well as a major site of HIV reservoir. No differences were found in FA suggesting no additional axonal injury due to HIV infection compared to alcohol use. Conversely, the effect of drinking level was not significant for any measures. This indicates that HIV infection is a potentially stronger source of neuro-inflammation compared to increased drinking, despite the fact that 20 out of 25 HIV+ subjects were virally suppressed (viral load<200 copies/ml). Lack of significant effect from drinking may be attributed to the small sample size of heavy drinkers (n=8) compared to moderate drinkers (n=35). This, along with absence of non-alcoholic/HIV- controls will be addressed in the future. We will also carry out a longitudinal study on the same population with a second MRI scan after 30 days of alcohol abstinence to determine the effects of alcohol recovery with and without HIV infection on the brain.Conclusion

While neuro-inflammation is a feature of both chronic alcoholism and HIV infection, our results suggest that presence of HIV, even among virally suppressed PLWH, is a more significant factor contributing to brain inflammation compared to an increase in drinking level.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Kader R, Govender R, Seedat S, Koch JR, Parry C. Understanding the Impact of Hazardous and Harmful Use of Alcohol and/or Other Drugs on ARV Adherence and Disease Progression. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125088.

2. Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, Samet JH. Alcohol Use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Current Knowledge, Implications, and Future Directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(10):2056-2072.

3. Ash MK, Al-Harthi L, Schneider JR. HIV in the Brain: Identifying Viral Reservoirs and Addressing the Challenges of an HIV Cure. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(8).

4. Lanquetin A, Leclercq S, de Timary P, et al. Role of inflammation in alcohol-related brain abnormalities: a translational study. Brain Commun. 2021;3(3):fcab154.

5. Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(3):717-730.

6. Hoy AR, Koay CG, Kecskemeti SR, Alexander AL. Optimization of a free water elimination two-compartment model for diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2014;103:323-333.

7. Uddin MN, Faiyaz A, Wang L, et al. A longitudinal analysis of brain extracellular free water in HIV infected individuals. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8273.

8. Drinking Levels Defined. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed.

9. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):782-790.

10. Garyfallidis E, Brett M, Amirbekian B, et al. Dipy, a library for the analysis of diffusion MRI data. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:8.

11. Nath A. Eradication of human immunodeficiency virus from brain reservoirs. Journal of neurovirology. 2015;21(3):227-234.

12. Zahr NM, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Perspectives on fronto-fugal circuitry from human imaging of alcohol use disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2017;122:189-200.

13. Oishi K, Faria A, Jiang H, et al. Atlas-based whole brain white matter analysis using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping: application to normal elderly and Alzheimer's disease participants. Neuroimage. 2009;46(2):486-499.

14. Ceritoglu C, Tang X, Chow M, et al. Computational analysis of LDDMM for brain mapping. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:151.

Figures