0027

Neuroinflammation and amyloid deposition in the progression of mixed Alzheimer and vascular dementia1Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, United States, 2Department of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, United States, 3Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, United States, 4Department of Neurosurgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Dementia, Dementia

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) pathologies commonly coexist in community-dwelling elderly. It is not discernible whether neuroinflammation and amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition are distinct or entangled pathophysiological mechanisms in patients with mixed AD and VCID pathologies. In this study, we found that neuroinflammation (measured by 11C-PK11195 uptake) but not Aβ deposition (measured by 11C-PiB binding), contributes to white matter hyperintensities baseline volume and progression. Both neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition independently contribute to cognitive impairment progression. Neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition represent two distinct pathophysiological pathways in elderly participants with mixed AD and VCID pathologies.Introduction

Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) represents a spectrum of underlying pathological processes leading to cerebrovascular brain injury and dementia. Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. AD and VCID pathologies commonly coexist in community-dwelling elderly (1). White matter hyperintensities (WMH) of presumed vascular and ischemic origin (2) are often found in patients with AD and VCID (3,4). Mixed pathology increases the odds of dementia by almost three times.The pathogenic mechanisms underlying disease risk and progression are not completely understood in mixed AD and VCID. Amyloid beta peptide (Aβ) aggregates define a key pathological feature of AD. Neuroinflammation may be a pathophysiological mechanism in both AD and VCID (5,6). It is not discernible whether neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition are distinct or entangled pathophysiological mechanisms. Using a longitudinal study, we aimed to investigate the role of neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition in WMH and cognitive function at baseline and their progression over a decade in patients with mixed AD and VCID pathologies.

Methods

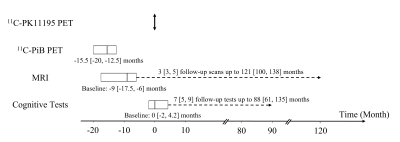

11C-PK11195 and 11C-PiB PET images were acquired to measure neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition, respectively. Twenty-four elderly participants (Age: 78 [64.8, 83] (Median [Interquartile range]); 14 female) were scanned at baseline and followed up for more than a decade. The longitudinal study timeline is provided in Figure 1. 11C-PK11195 PET scan time was used as the timepoint zero. 11C-PiB PET images were acquired at -15.5 [-20, -12.5] months. Baseline MR T1w MPRAGE and FLAIR images were acquired at -9 [-17.5, -6] months from 19 participants. Follow-up FLAIR images were acquired from 9 participants 3 [3, 5] times up to 121 [100, 138] months. Serial cognitive tests were performed at approximately 12-month intervals. The baseline cognitive data were acquired at 0 [-2, 4.2] months. Twenty-one participants had 7 [5, 9] follow-up cognitive assessments up to 88 [61, 135] months.11C-PK11195 regional standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) and 11C-PiB mean cortical binding potential (MCBP) were computed as PET imaging biomarkers of neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition, respectively. WMH lesions were delineated manually on FLAIR images. Normalized WMH volume was computed as a ratio of WMH lesion volume to brain tissue volume. Three standardized composite z-scores, zglobal, zspeed and zmemory, were calculated to assess global, processing speed, and memory functions, respectively. An overall vascular risk score was calculated to account for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack, and smoking. Multiple linear regression models evaluated the association between PET biomarkers (11C-PK11195 SUVR and 11C-PiB MCBP) and baseline WMH volume and cognitive function. Moreover, linear mixed-effects models with random participant effects were utilized to evaluate whether PET biomarkers predicted greater WMH progression or cognitive decline over a decade.

Results

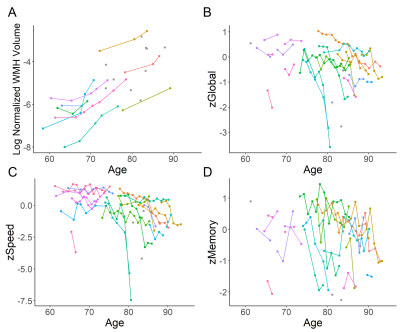

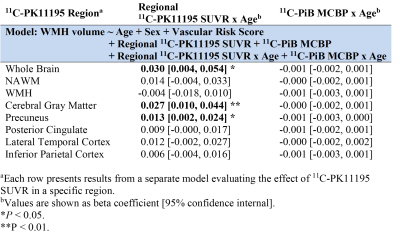

Fifteen participants (62.5%) had both a positive PiB scan (11C-PiB MCBP>0.18) and at least one vascular risk factor. The baseline WMH volume was 4.06 [2.14, 19.21] ml, corresponding to normalized WMH volume of 0.52% [0.22%, 2.30%]. Twenty-one (87.5%) and seventeen (70.8%) participants had normal MMSE (>=24) and CDR (=0), respectively, at baseline. Elevated 11C-PK11195 SUVR in whole brain (WB) (β=0.281, P=0.044) and gray matter (GM) (β=0.240, P=0.036) were associated with greater baseline WMH volume after controlling for age and vascular risk score.The longitudinal progression of WMH is demonstrated in Figure 2A. Elevated 11C-PK11195 SUVR in WB, GM and precuneus respectively predicted greater WMH progression, while elevated 11C-PiB MCBP did not (Table 1). The longitudinal decline of cognitive function is demonstrated in Figure 2(B-D). Elevated 11C-PK11195 SUVR in precuneus, lateral temporal cortex and inferior parietal cortex respectively predicted greater zGlobal decline independent of 11C-PiB MCBP (Table 2). Elevated 11C-PK11195 SUVR in WB, normal appearing white matter, lateral temporal cortex and inferior parietal cortex respectively predicted greater zSpeed decline independent of 11C-PiB MCBP (Table 2). Elevated 11C-PK11195 SUVR in inferior parietal cortex predicted greater zMemory decline independent of 11C-PiB MCBP. 11C-PiB MCBP was not associated with regional 11C-PK11195 SUVR (P>0.4).

Discussion

It is crucial that we understand the extent to which AD and VCID pathomechanisms contribute toward the neuroimaging manifestations and cognitive impairment in a personalized manner as therapeutics are developed (7,8). Neuroinflammation is an important pathomechanism in AD and VCID and may be a therapeutical target. We found widespread neuroinflammation in participants with high WMH burden but relatively normal functions (MMSE and CDR) at baseline. Neuroinflammation, but not pathologic Aβ deposition, was associated with baseline WMH volume and predicted its progression over 11.5 years. Both neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition independently predicted cognitive decline over 7.5 years after controlling for age, education, and vascular risk factors. Notably, there was no association between 11C-PK11195 SUVR and 11C-PiB MCBP, suggesting that neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition are two separate pathophysiological processes.Conclusion

Neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition represent two distinct pathophysiological pathways in a cohort of elderly participants with mixed AD and VCID pathologies. Neuroinflammation plays a role in the development of WMH early in the course of the disease. Both neuroinflammation and Aβ deposition independently contribute to the progression of cognitive impairments.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH): P01AG026276, P01AG003991, P30AG066444, 1R01AG054567, R01HL129241, 1R01NS082561, 1P30NS098577, RF1NS116565, R21NS127425, R01NS085419, U24NS107230, KL2TR002346, R03AG072375 and R01AG074909. Additional support was generously provided by the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Research Initiative and by the Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan Fund and the Paula and Rodger Riney Funding.References

1. Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology 2007;69(24):2197-2204.

2. Kang P, Ying C, Chen Y, Ford AL, An H, Lee JM. Oxygen Metabolic Stress and White Matter Injury in Patients With Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Stroke 2022;53(5):1570-1579.

3. Alber J, Alladi S, Bae H-J, Barton DA, Beckett LA, Bell JM, Berman SE, Biessels GJ, Black SE, Bos I. White matter hyperintensities in vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID): knowledge gaps and opportunities. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2019;5:107-117.

4. Lee S, Viqar F, Zimmerman ME, Narkhede A, Tosto G, Benzinger TL, Marcus DS, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Buckles V, Ghetti B, McDade E, Martins RN, Saykin AJ, Masters CL, Ringman JM, Ryan NS, Forster S, Laske C, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Salloway S, Correia S, Jack C, Jr., Weiner M, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Mayeux R, Brickman AM, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N. White matter hyperintensities are a core feature of Alzheimer's disease: Evidence from the dominantly inherited Alzheimer network. Ann Neurol 2016;79(6):929-939.

5. Wu C, Li F, Niu G, Chen X. PET imaging of inflammation biomarkers. Theranostics 2013;3(7):448-466.

6. Werry EL, Bright FM, Piguet O, Ittner LM, Halliday GM, Hodges JR, Kiernan MC, Loy CT, Kril JJ, Kassiou M. Recent Developments in TSPO PET Imaging as A Biomarker of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20(13).

7. Rosenberg GA, Prestopnik J, Knoefel J, Adair JC, Thompson J, Raja R, Caprihan A. A Multimodal Approach to Stratification of Patients with Dementia: Selection of Mixed Dementia Patients Prior to Autopsy. Brain Sci 2019;9(8).

8. Cipollini V, Troili F, Giubilei F. Emerging Biomarkers in Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: From Pathophysiological Pathways to Clinical Application. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20(11).

Figures