0007

Submillimeter T1 Atlas for Subject-Specific Abnormality Detection at 7T

Gian Franco Piredda1,2,3, Samuele Caneschi1, Tom Hilbert1,4,5, Gabriele Bonanno1,6,7, Arun Joseph1,6,7, Karl Egger8, Jessica Peter9, Stefan Klöppel9, Elisabeth Jehli10,11, Matthias Grieder10, Johannes Slotboom12, David Seiffge13, Martina Goeldlin13, Robert Hoepner13, Tom Willems14, Serge Vulliemoz15, Margitta Seeck15, Punith B. Venkategowda16, Ricardo A. Corredor Jerez1,4,5, Bénédicte Maréchal1,4,5, Jean-Philippe Thiran4,5, Roland Weist6,12, Tobias Kober1,4,5, and Piotr Radojewski6,12

1Advanced Clinical Imaging Technology, Siemens Healthineers International AG, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Human Neuroscience Platform, Fondation Campus Biotech Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, 3CIBM-AIT, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 4Department of Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 5LTS5, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 6Translational Imaging Center (TIC), Swiss Institute for Translational and Entrepreneurial Medicine, Bern, Switzerland, 7Magnetic Resonance Methodology, Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 8Department of Neuroradiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 9University Hospital of Old Age Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 10Translational Research Center, University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 11Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 12Support Center for Advanced Neuroimaging, Institute for Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, Inselspital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 13Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Bern, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 14Institute of Psychology, University of Bern, Geneva, Switzerland, 15EEG & Epilepsy Unit, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Geneva University Hospitals & Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland, 16Siemens Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India

1Advanced Clinical Imaging Technology, Siemens Healthineers International AG, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Human Neuroscience Platform, Fondation Campus Biotech Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, 3CIBM-AIT, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 4Department of Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 5LTS5, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 6Translational Imaging Center (TIC), Swiss Institute for Translational and Entrepreneurial Medicine, Bern, Switzerland, 7Magnetic Resonance Methodology, Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 8Department of Neuroradiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 9University Hospital of Old Age Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 10Translational Research Center, University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 11Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 12Support Center for Advanced Neuroimaging, Institute for Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, Inselspital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 13Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Bern, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 14Institute of Psychology, University of Bern, Geneva, Switzerland, 15EEG & Epilepsy Unit, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Geneva University Hospitals & Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland, 16Siemens Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India

Synopsis

Keywords: YIA, Tissue Characterization, Acquisition & Analysis, Quantitative Imaging, Ultra-high field MRI

Databases of normative values from healthy tissues are needed to leverage the improved comparability and hardware independence of quantitative MRI, and thus enable patient-specific detection of abnormalities in visual interpretation. Here, we present normative atlases of T1 relaxation times in the brain at 3T (1 mm isotropic) and 7T (0.6 mm isotropic) from two large cohorts of healthy subjects. The atlases were tested in single‐subject comparisons for detection of abnormal relaxation times in patients scanned at both field strengths. The presented detection of subtle alterations not visible in conventional MRI showed the clinical potential of the method.Introduction:

Quantitative MRI (qMRI) allows moving from a relative MR contrast information susceptible to various confounding factors to – ideally – absolute measures of physical properties, thus providing the means to characterize tissues and gain insight into subtle microstructural changes caused by diseases1–4. However, to fully benefit from quantitative maps, normative values in healthy tissue are required, enabling the comparison of tissue properties from a single patient to healthy cohorts.In a previous study at 3T, we proposed a framework that enables voxel-wise comparison of brain qMRI maps to normative values in a single-patient setting5. The application of this method in subsequent studies has shown that quantitative T1 deviations from normative values are more correlated with patients’ disability than conventional MRI-based metrics6–8.

In this context, the improved SNR of high-resolution MR images acquired at 7T can add clinical value. In this study, we establish a method for single-patient analysis of quantitative T1 values at 7T by building an atlas of normative T1 values from a healthy cohort. Example deviation maps are evaluated in patients with different neurological conditions scanned at both 3T and 7T.

Methods:

Study population and MR protocolTwo separate healthy cohorts were recruited at two different field strengths:

- 3T (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany): 205 subjects (122 females, median age = 31y/o, range = [20-78]y/o);

- 7T (MAGNETOM Terra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany): 127 subjects (68 females, median age = 28y/o, range = [15-74]y/o).

For a proof-of-principle, the following patients were scanned both at 3T and 7T:

- Two patients (female, 29y/o; and male, 37y/o) with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) and relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS);

- Two patients (male, 56y/o; and male, 39y/o) with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL);

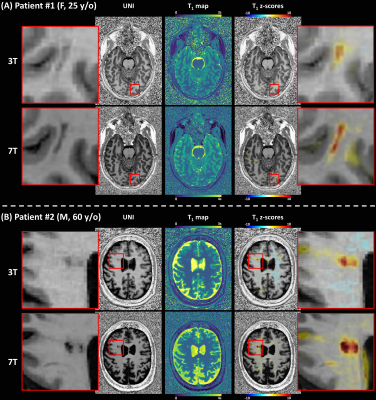

- Two patients (female, 25y/o; and male, 60y/o) with focal epilepsy.

Total intracranial volume and brain segmentation masks were obtained for each subject using the MorphoBox11 research application, whose skull-stripping module was adapted for 7T MP2RAGE T1-weighted uniform (UNI) images12–14.

A study-specific template (SST) was built for each of the two healthy cohorts15,16. Skull-stripped UNI images of the healthy subjects were spatially co-registered onto the respective SST with a non-linear registration17, and the estimated transformation was applied to the T1 maps and segmentation masks.

Normative atlases

In the field-strength-specific SST space, an atlas of T1 values in healthy tissues was established by modelling voxel-wise ($$$\vec{r}$$$) the T1 inter-subject variability with age and sex:

$$E\{T_1(\vec{r})\}=\beta_{0}(\vec{r})+\beta_{sex}(\vec{r})*sex+\beta_{age}(\vec{r})*age+\beta_{age^2}(\vec{r})*age^2\,,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,(1)$$with $$$sex = 1$$$ if the subject is male, 0 if female. The age regressor was centered at the mean age of the healthy cohorts, and a quadratic term was included18–21. Root mean squared errors (RMSE) were evaluated as an estimation of the standard deviation of the residual errors. The SST and the established atlas at 7T were made available online: https://central.xnat.org/data/projects/7T_T1_atlas.

The analysis was restricted to non-cortical voxels to mitigate false‐positives in the cortex5.

Single-subject comparison

In the patient datasets, deviations from established atlases were expressed in z-score maps, calculated voxel-wise ($$$\vec{r}$$$) as: (T1($$$\vec{r}$$$)-E{T1($$$\vec{r}$$$)})/RMSE($$$\vec{r}$$$), with T1($$$\vec{r}$$$) being the measured T1 in the patient’s dataset5.

Results:

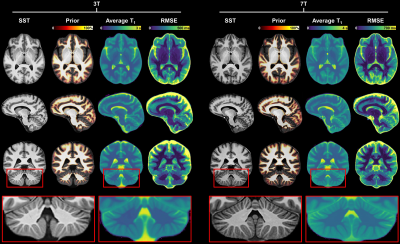

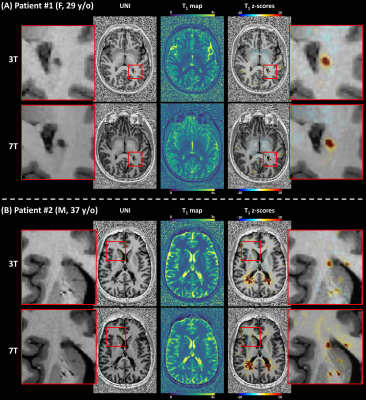

Example slices of the T1 atlases are shown in Figure 1. A better delineation of anatomical details and tissue boundaries can be observed at 7T. Expected average T1 relaxation times in WM were found to be E{T1,3T}±RMSE3T = 826±38 ms, E{T1,7T}±RMSE7T = 1228±53 ms. A similar coefficient of variation was thus observed at 3T and 7T, 4.6% and 4.3%, respectively.In the RIS patient, the analysis revealed T1 abnormalities (defined as T1 z-scores > 2) localized only within the visible lesion (Figure 2A). In the RRMS patient, subtle diffuse abnormalities in 7T T1 values were also found in the normal-appearing WM, that were less pronounced at 3T (Figure 2B).

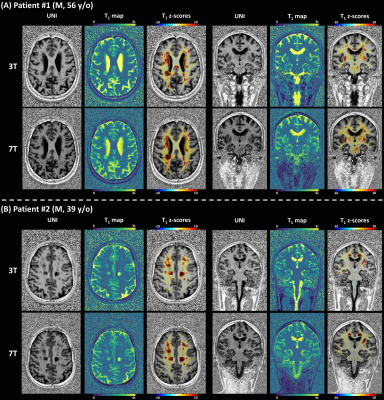

In the CADASIL patient with the disease duration of 22 years (Figure 3A), more pronounced T1 z-score deviations were observed in both lacunar WM lesions and normal-appearing tissues compared to the second patient with a shorter disease duration of 4.5 years (Figure 3B).

In one epilepsy patient with suspected focal cortical dysplasia in the right parietal lobe, 7T MRI revealed an additional abnormality in the periventricular region of the left occipital lobe, better delineated by the T1 z-score analysis at 7T than at 3T (Figure 4A). In the second epilepsy patient, abnormal T1 z-scores were observed in a heterogenous atypical lesion in the deep WM, suggestive of focal cortical dysplasia (Figure 4B).

Discussion & Conclusion:

The present work introduces a method for personalized detection of brain abnormalities inducing changes of the T1 relaxation time. The feasibility of performing single‐patient comparisons was shown in example case studies with various conditions. The possibility of detecting subtle alterations that are not visible in conventional MRI shows the method’s clinical potential. The detection of widespread global changes in normal-appearing brain tissue may allow a deeper understanding of disease pathophysiology and more precise assessment of tissue damage for both differential diagnosis and follow-up6–8. Atlas-based single-subject analysis thus represents a promising tool looking beyond the visible changes often reflecting only the “tip of the iceberg” of the underlying pathology.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Tofts P. Quantitative MRI of the Brain: Measuring Changes Caused by Disease. John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

- Deoni SCL. Quantitative Relaxometry of the Brain. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;21(2):101-113. doi:10.1097/RMR.0b013e31821e56d8

- Weiskopf N, Mohammadi S, Lutti A, Callaghan MF. Advances in MRI-based computational neuroanatomy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28(4):313-322. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000222

- Weiskopf N, Edwards LJ, Helms G, Mohammadi S, Kirilina E. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of brain anatomy and in vivo histology. Nat Rev Phys. 2021;3(8):570-588. doi:10.1038/s42254-021-00326-1

- Piredda GF, Hilbert T, Granziera C, et al. Quantitative brain relaxation atlases for personalized detection and characterization of brain pathology. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83(1):337-351. doi:10.1002/mrm.27927

- Ravano V, Piredda GF, Vaneckova M, et al. T1 abnormalities in atlas-based white matter tracts: reducing the clinico-radiological paradox in multiple sclerosis using qMRI. In: Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. ; 2021:2796.

- Piredda GF, Hilbert T, Vaneckova M, et al. Quantitative T1 deviations in brain lesions and NAWM improve the clinico-radiological correlation in early ms. In: MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS JOURNAL. Vol 26. SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD 1 OLIVERS YARD, 55 CITY ROAD, LONDON EC1Y 1SP, ENGLAND; 2020:418.

- Vaneckova M, Piredda GF, Andelova M, et al. Periventricular gradient of T1 tissue alterations in multiple sclerosis. NeuroImage Clin. 2022;34:103009. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103009

- Marques JP, Kober T, Krueger G, van der Zwaag W, Van de Moortele P-F, Gruetter R. MP2RAGE, a self bias-field corrected sequence for improved segmentation and T1-mapping at high field. Neuroimage. 2010;49(2):1271-1281. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.002

- Mussard E, Hilbert T, Forman C, Meuli R, Thiran JP, Kober T. Accelerated MP2RAGE imaging using Cartesian phyllotaxis readout and compressed sensing reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84(4):1881-1894. doi:10.1002/mrm.28244

- Schmitter D, Roche A, Maréchal B, et al. An evaluation of volume-based morphometry for prediction of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;7:7-17. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2014.11.001

- Venkategowda PB, Kumaraswamy AK, Richiardi J, et al. Retrofitting a Brain Segmentation Algorithm with Deep Learning Techniques: Validation and Experiments. In: Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ; 2020:3566.

- Piredda GF, Venkategowda PB, Radojewski P, et al. Automated brain morphometry for sub-millimeter 7T MRI using transfer learning. In: Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, London, UK. ; 2022:Abstract: 2155.

- Piredda GF, Caneschi S, Hilbert T, et al. Submillimeter T1 atlas for subject‐specific abnormality detection at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2023;89(4):1601-1616. doi:10.1002/mrm.29540

- Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2033-2044. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025

- Avants BB, Yushkevich P, Pluta J, et al. The optimal template effect in hippocampus studies of diseased populations. Neuroimage. 2010;49(3):2457-2466.

- Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim J. elastix: A Toolbox for Intensity-Based Medical Image Registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29(1):196-205. doi:10.1109/TMI.2009.2035616

- Badve C, Yu A, Rogers M, et al. Simultaneous T1 and T2 brain relaxometry in asymptomatic volunteers using magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Tomogr a J imaging Res. 2015;1(2):136. doi:10.18383/j.tom.2015.00166

- Okubo G, Okada T, Yamamoto A, Fushimi Y, Okada T, Togashi K. Age-related change of the whole brain T1 relaxation time: voxel-wise study with MP2RAGE. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of ISMRM. ; 2017:2338. http://cds.ismrm.org/protected/17MPresentations/abstracts/2338.html.

- Slater DA, Melie‐Garcia L, Preisig M, Kherif F, Lutti A, Draganski B. Evolution of white matter tract microstructure across the life span. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(7):2252-2268. doi:10.1002/hbm.24522

- Hagiwara A, Fujimoto K, Kamagata K, et al. Age-Related Changes in Relaxation Times, Proton Density, Myelin, and Tissue Volumes in Adult Brain Analyzed by 2-Dimensional Quantitative Synthetic Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest Radiol. 2021;56(3):163-172. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000000720

Figures

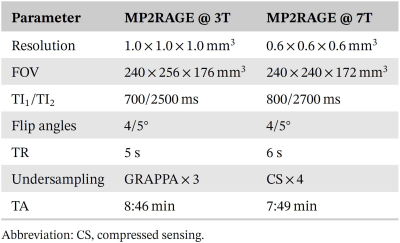

Table 1. Parameters of the acquired MP2RAGE sequence at

3T and 7T.

Figure 1. Representative slices of the established T1

atlases at 3T and 7T. The displayed a priori probabilistic segmentation is

overlaid onto the study-specific template (SST) and represents the probability

of each voxel in the SST space to belong to WM or subcortical structures. The

average T1 corresponds to the intercept coefficient

of Eq. 1 (i.e., the average T1 at

the mean age of the two cohorts, 35 y for 3T, and 33 y for 7T). A better

delineation of anatomical details and tissue boundaries can be observed in the

7T atlas. RMSE: root mean squared error.

Figure 2. Z-score maps resulting from a single-subject

comparison against voxel-based population-derived norms overlaid on a

representative UNI axial slice for a patient diagnosed with radiologically

isolated syndrome (A), and patient diagnosed with relapsing–remitting multiple

sclerosis (B).

Figure 3. Z-score maps resulting from a single-subject

comparison against voxel-based population-derived norms overlaid on

representative UNI axial and coronal slices for two patients with confirmed

(patient 1, 22 years of disease duration) and strong clinical suspicion of

(patient 22, 4.5 years of disease duration) cerebral autosomal dominant

arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy.

Figure 4. Z‐score maps resulting from a single‐subject comparison against voxel‐based population‐derived norms overlaid on a representative UNI

axial slice for two patients diagnosed with epilepsy.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0007