0004

Measurement of Magnetostimulation Thresholds in the Porcine Heart

Valerie Klein1,2,3, Jaume Coll-Font2,3,4, Livia Vendramini2, Donald Staney2, Mathias Davids2,3, Natalie G. Ferris2,5, Lothar R. Schad1,6, David E. Sosnovik2,3,4,5, Christopher Nguyen7,8,9, Lawrence L Wald2,3,5, and Bastien Guérin2,3

1Computer Assisted Clinical Medicine, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany, 2A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 3Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 4Cardiovascular Research Center, Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 5Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States, 6Mannheim Institute for Intelligent Systems in Medicine, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany, 7Cardiovascular Innovation Research Center, Heart Vascular & Thoracic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 8Department of Radiology, Imaging Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 9Department of Biomedical Engineering, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States

1Computer Assisted Clinical Medicine, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany, 2A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 3Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 4Cardiovascular Research Center, Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 5Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States, 6Mannheim Institute for Intelligent Systems in Medicine, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany, 7Cardiovascular Innovation Research Center, Heart Vascular & Thoracic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 8Department of Radiology, Imaging Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 9Department of Biomedical Engineering, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: YIA, Heart

High-amplitude gradient systems can surpass the IEC regulatory limit for cardiac stimulation (CS), which is based on animal electrostimulation data and simplified electromagnetic modeling. We assess CS in MRI by performing the first cardiac magnetostimulation threshold measurements in pigs, the primary animal model of the human cardiovascular system. We use the measurements to validate a detailed CS modeling pipeline applicable to both pigs and humans. Experimental thresholds and predictions in porcine-specific models agree within 19% NRMSE. CS modeling in a detailed human body model indicates that CS thresholds of the Connectome gradient are ~25-fold greater than the IEC CS limit.Purpose:

Time-varying MRI gradient fields induce electric fields (E-fields) in the patient, which can induce peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) and potentially cardiac stimulation (CS)[1-4]. Unlike PNS, cardiac magnetostimulation thresholds cannot be safely measured in humans. Instead, the IEC 60601-2-33 standard[5] imposes limits on the switching speed of gradient systems to prevent CS, based on electrode measurements in different species and on simplistic electromagnetic (EM) field simulations in a homogeneous body model[2,6]. For long rise-time waveforms and high-amplitude gradient systems like the Connectome[7], the IEC CS limit can become more constraining than the PNS limit. We assess CS in MRI using a combination of cardiac magnetostimulation measurements in pigs and detailed simulations combining state-of-the-art EM and electrophysiological modeling.Methods:

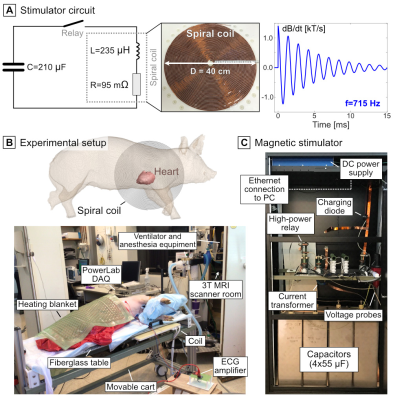

Measurement of porcine CS thresholds: We measured cardiac magnetostimulation thresholds in pigs[8], a widely used animal model of the human cardiovascular system[9]. All experiments were conducted with the approval and under the advice of the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. CS thresholds were measured in ten anesthetized pigs by discharging a capacitor bank into a spiral coil close to the torso, resulting in a damped sinusoidal dB/dt waveform (f=715 Hz, Figure 1)[8]. Capacitor discharges were triggered immediately after the T-wave (early diastole) and before the P-wave (late diastole), based on ECG recordings. The stimulus amplitude was increased by increasing the capacitor voltage until cardiac capture was detected on ECG, blood pressure, or peripheral oximetry traces. The CS thresholds were then determined by fitting sigmoid functions to the binary cardiac responses as a function of the capacitor voltage.Porcine-specific body models: Immediately after the stimulation experiment, fat/water-separated Dixon (multiple bed positions) and CINE images were acquired in eight of the pigs (#1-#4 and #7-#10) using a 3T MRI scanner (Connectome, Siemens Healthineers, Germany)[8]. The MRI datasets were segmented manually and interpolated to 1 mm3 isotropic resolution to create individualized body models reflecting the anatomy and posture of the animals. Tissues were assigned conductivity values based on the IT’IS low frequency database[10]. Finally, cardiac Purkinje and ventricular muscle fiber paths were added to the heart of each porcine body model using rule-based modeling algorithms[11,12].

Prediction of CS thresholds: We used our EM-electrophysiological CS modeling pipeline[13] to predict CS thresholds in the individualized porcine body models for the spiral coil, and in a female human body model placed in the Connectome gradient system (head at isocenter). In short, we project the predicted E-field onto 3D paths of cardiac Purkinje and ventricular muscle fibers to calculate the electrical potential along all excitable fibers. The potential is modulated in time by the coil current waveform derivative and input into validated electrophysiological cardiac fiber models to identify the smallest coil current waveform inducing an action potential in any fiber.

Results:

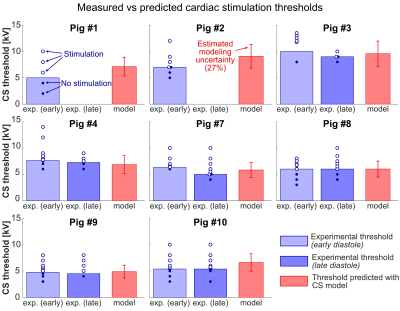

ECG and oximetry signals measured in pig #6 show that a capacitor discharge at U=5.0 kV did not cause cardiac capture, whereas an increase to U=5.25 kV capacitor voltage did (Figures 2A&B). No cardiac arrhythmias were induced in any of the pigs other than a single premature ventricular contraction in pig #4 (Figure 2C). The average CS threshold measured in the ten pigs during early diastole was 6.27±1.33 kV, which corresponds to dB/dt=1.60±0.22 kT/s at heart center and a 95th percentile E-field E95=92.9±13.5 V/m over the myocardium. Thresholds measured during early and late diastole were not significantly different (p<0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test).Figure 3 shows a porcine body model (including cardiac fibers) and E-fields simulated for the spiral coil. Figure 4 compares measured and predicted thresholds for the eight pigs with animal-specific body models. Modeling predictions and experimental thresholds agree within 19% (NRMSE), and no significant difference was found between them (p<0.05, paired t-test). In all cases, the predicted Purkinje thresholds were >5-fold higher than ventricular fiber thresholds, thus setting the effective CS threshold. We estimated the CS modeling uncertainty to be 27% by propagating the uncertainties of each of the 25 main model parameters through the modeling pipeline.

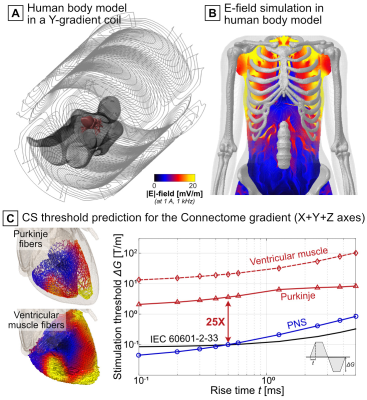

Figure 5 shows CS threshold predictions in a female human body model for the Connectome gradient (X+Y+Z axis combination, trapezoidal gradient waveform with 500-µs flat-top duration). The predicted CS thresholds were 25-fold higher than the IEC CS limit and the PNS limit at trise=0.5 ms.

Discussion:

We performed the first measurements of cardiac magnetostimulation thresholds in ten healthy, anesthetized pigs[8]. To analyze this data, we created individualized body models reflecting the anatomy and posture of the animals during stimulation. The average dB/dt in the porcine heart at the measured threshold was 1.60±0.22 kT/s. This value is 11 times higher than the human IEC CS limit at f=715 Hz.The measurements agree with threshold predictions in the porcine-specific models within 19%, supporting the validity of the CS model. Predictions for the Connectome gradient coil loaded with a realistic female human body model suggest that the CS thresholds are substantially greater than either the PNS thresholds measured for that coil or the IEC CS limit. Our CS model will be a useful tool for informing safety limits for MRI gradients that protect patients without overly restricting gradient performance and thus imaging speed and resolution.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jo Hyun Kim, Shi Chen, and Robert Alan Eder for their help with the experiments. The research reported in this publication was in part supported by the ISMRM Research Exchange Grant and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) as well as by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01EB028250, P41EB030006, R01HL151704, and R01HL159010. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.References

[1] Irnich W. Electrostimulation by time-varying magnetic fields. MAGMA. 1994;2:43-49.

[2] Reilly J P. Magnetic field excitation of peripheral nerves and the heart: A comparison of thresholds. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1991;29:571-579.

[3] Bourland J D, Nyenhuis J A, Schaefer D J. Physiologic effects of intense MR imaging gradient fields. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 1999;9(2):363-377.

[4] Schaefer D J, Bourland J D, Nyenhuis J A. Review of patient safety in time-varying gradient fields. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:20-29.

[5] IEC, International standard IEC 60601 medical electrical equipment. Part 2-33: Particular requirements for the basic safety and essential performance of magnetic resonance equipment for medical diagnosis. 2010, International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC).

[6] Reilly J P. Principles of nerve and heart excitation by time-varying magnetic fields. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;649:96-117.

[7] Setsompop K, Kimmlingen R, Eberlein E, Witzel T, Cohen-Adad J, McNab J A, Keil B, Tisdall M D, Hoecht P, Dietz P, Caluey S F, Tountcheva V, Matschl V, Lenz V H, Heberlein K, Potthast A, Thein H, Van Horn J, Toga A, Schmitt F, Lehne D, Rosen B R, Wedeen V, Wald L L. Pushing the limits of in vivo diffusion MRI for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage. 2013;80:220-233.

[8] Klein V, Coll-Font J, Vendramini L, Straney D, Davids M, Ferris N G, Schad L R, Sosnovik D E, Nguyen C T, Wald L L, Guérin B. Measurement of magnetostimulation thresholds in the porcine heart. Magn Reson Med. 2022;88:2242-2258.

[9] Dixon J A and Spinale F G. Large animal models of heart failure. Circ. 2009;2(3):262-271.

[10] Hasgall P A, Di Gennaro F, Baumgartner C, Gosselin M C, Payne D, Klingenböck A, Kuster N. IT’IS Database for thermal and electromagnetic parameters of biological tissues Version 4.0. 2018.

[11] Ijiri T, Ashihara T, Yamaguchi T, Takayama K, Igarashi T, Shimada T, Namba T, Haraguchi R, Nakazawa K. A procedural method for modeling the Purkinje fibers of the heart. J Physiol Sci. 2008;58(7):481-486.

[12] Bayer J D, Blake R C, Plank G, Trayanova N A. A novel rule-based algorithm for assigning myocardial fiber orientation to computational heart models. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(10):2243-2254.

[13] Klein V, Davids M, Schad L R, Wald L L, Guérin B. Investigating cardiac stimulation limits of MRI gradient coils using electromagnetic and electrophysiological simulations in human and canine body models. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85:1047–1061.

[14] Stewart P, Aslanidi O V, Noble D, Noble P J, Boyett M R, Zhang H. Mathematical models of the electrical action potential of Purkinje fibre cells. Phil Trans R Soc A. 2009;367:2225-2255.

[15] O'Hara T, Virág L, Varró A, Rudy Y. Simulation of the undiseased human cardiac ventricular action potential: Model formulation and experimental validation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7(5):e1002061.

Figures

Figure 1: Circuit diagram and implementation of the magnetic stimulator, and experimental setup of the CS study in anesthetized pigs. Upon closing of a high-power relay, the capacitors (C=210 µF) discharged into a flat spiral coil (L=235 µH, R=95 mΩ, 38 turns of 2.3-mm insulated copper wire) placed underneath the pig’s torso and centered on the heart. The discharge created a damped sinusoidal dB/dt waveform oscillating at 715 Hz whose amplitude was determined by the capacitor voltage (Umax=18 kV). The maximum dB/dt at coil center was 26.7 kT/s and 4.6 kT/s 11 cm from center.

Figure 2: ECG and blood oximetry traces. The electromagnetic pulse (dashed blue

line) was applied after the T-wave (early diastole). A) Pig #6

sub-threshold traces following U=5.0 kV (no stimulation). B) Pig #6

supra-threshold traces following U=5.25 kV, showing a premature T-wave (cardiac

capture) followed by a compensatory pause, after which normal anterograde

conduction resumed. C) Supra-threshold traces from pig #4 showing a

premature T-wave followed by a QRS complex with abnormal morphology consistent

with a single premature ventricular contraction (PVC).

Figure 3: A) Dixon

and CINE data were segmented to create individualized body models replicating

the anatomy and posture of each animal under study. E-fields were simulated in

the porcine body models using the magnetoquasistatic EM solver by Sim4Life

(Zurich MedTech, Switzerland). B) Cardiac Purkinje and ventricular

muscle fibers were added to the porcine body models using rule-based modeling

algorithms[11,12]. The fiber response to the extracellular electric

potential was simulated with electrical circuit models of cardiac cells[14,15] connected by

resistive gap junctions.

Figure 4: Comparison of measured (blue bars) and model-predicted (red bars) CS

thresholds in the eight animals with body models. Experimental thresholds were

measured during early and late diastole; dots show single measurements (open:

stimulation, closed: no stimulation). We observed CS in all animals for early

diastole stimulation. No late diastole measurements were made in pigs #1 and

#2. Red error bars indicate modeling uncertainty (27%) from the sensitivity

analysis. No significant differences were found between measured and predicted

thresholds (p<0.05, paired t-test).

Figure 5: The porcine measurements provided validation of a general modeling framework that can be applied to human modeling. Shown here are CS simulation results for the Connectome gradient (X+Y+Z axes) loaded with a human female body model. A) Body model (only skin and myocardium shown out of the 25 tissue classes) and gradient coil. B) Simulated E-field. C) Predicted CS thresholds (red curves), IEC CS limit (black), and experimental PNS thresholds[7] (blue). Thresholds were predicted for a gradient waveform with ten bipolar pulses, linear ramps, and a 500-µs flat-top duration.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0004