5065

Are low dose CT scouts suitable for MRI safety screening of subjects with unknown medical history?1King's College Hospital, london, United Kingdom, 2Royal Marsden Hospital, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Increasing numbers of patients are presenting for MRI who cannot complete the safety questionnaires. CT scout images have low radiation dose, and are faster and easier to acquire compared to plain film x-rays, the recommended modality for MR safety screening for patients with unknown history. This study assesses the performance of CT scout images in detecting and identifying a range of head/neck and body implants. Using 40 head/neck and 40 body CT scouts, two Readers reviewed the images for possible internal implants. 88% of implants were found and correctly identified, concluding that the majority of visible implants are detectable.

Introduction

The use of MRI in the acute setting is increasing[1,2,3], and tertiary referral centres are seeing larger numbers of patients for whom complete and accurate medical histories are not available to the MRI team, particularly for urgent scans. When screening patients who are not able to provide their own histories, or for whom such histories cannot be reliably obtained from others, and previous imaging is not available, plain film x-rays are recommended to identify implants. These should include the head/neck, chest, abdomen/pelvis, and the extremities if there are obvious post-traumatic changes[4,5]. However, acquiring plain film x-rays in multiple projections and positions can be difficult, especially for trauma or non-compliant patients, as it requires a significant amount of manual handling and potentially multiple operators. The quality of the images is also affected by operator experience, patient body habitus, and position. CT scout images have low radiation dose, are faster and easier to acquire compared to plain film x-rays[6], and have been used in other settings for screening procedures [7,8]. However, their suitability for MRI safety screening has not yet been evaluated. In this study we assess the performance of CT scouts in detecting and identifying of a range of head/neck and body implants.Methods

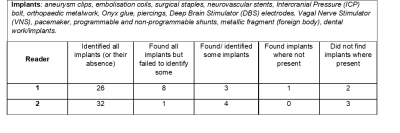

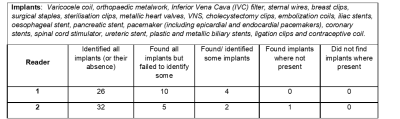

40 head/neck and 40 body CT scouts were selected, and a subset of these included one or multiple internal implants (medical and non-medical, Fig. 1 and 2) whose presence is not detectable by visually inspecting the patient. Two readers were presented the images in random order and asked to review them for possible implants. The readers, one medical physicist (MR Safety Expert, Reader 1) and one senior MRI radiographer (Reader 2), inspected the CT scouts on the PACS system, and were blind to any other patient details or image sets.Results

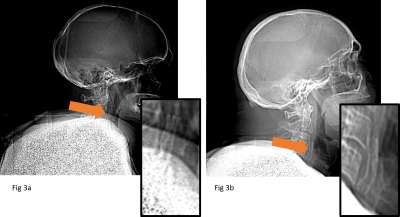

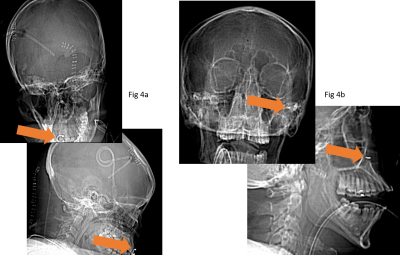

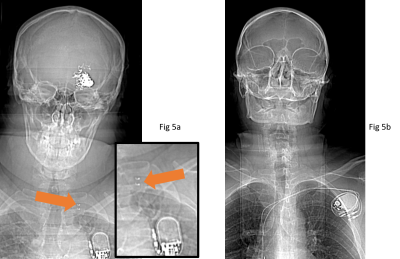

The tables in Fig. 1 and 2 summarise the reader’s scores. In 88% of cases the readers found all implants (or their absence), and in 73% of cases they correctly identified them. In 8% of cases, at least one implant was missed within an image containing multiple implants. Both readers scored similarly, with a slightly better performance in both finding and identifying implants from Reader 2, a clinical operator with more experience in reviewing CT images. Both readers failed to identify two neurovascular stents, two coronary stents, and one of the three carotid stents (Fig. 3a). Both readers also missed a hidden frenum piercing, which was present within a projection with multiple implants (Fig. 4a). However, a small metallic foreign body was correctly identified despite being superimposed over the dense bone of the skull base (Fig. 4b). Additionally, Reader 1 missed an iliac stent and a breast clip. From the list of implants included in this work, all high-risk implants that have led to documented injuries or death following MRI, such as aneurysm clips and active implants, were identified. All active implants were recognised as such, but in some cases were incorrectly identified (e.g., pacemaker instead of VNS, Fig. 5).Discussion

Although CT scouts have generally lower resolution and diagnostic quality than plain film x-rays, they led to identification of most of the implants listed in Fig. 1 and 2. These two readers were chosen as they have different expertise and experience, but are both directly involved in decisions regarding patient safety in MRI. While clinical experience in reviewing CT images was an advantage, it was felt that both readers’ results could be improved in some cases with training or further experience. The presence of two projections, both an anterior-posterior and lateral, helped to localise the position of an implant and to differentiate implants from internal pathology. This informs on the importance of multiple projections in any plain film modality. However, some implants were not visible in the images. Both the neurovascular and coronary stents could not be detected as, despite being radiopaque, they are very small[9,10] and had too fine a mesh to be depicted by this type of imaging. Similarly, carotid stents or IVC filters, which consist of fine metallic components, although visible, can be partially obscured by anatomy in a crowded projection (Fig. 4). Furthermore, as in the case of the missed frenum piercing (Fig. 4a), rare or unexpected implants might be difficult to find, possibly regardless of the imaging modality, further highlighting the need for specific skills and training.Conclusions

Within the selected set of implants, all those considered at high-risk when exposed to MRI were found on CT scouts, even with often multiple distracting elements within the images. CT scouts are already being used as a screening tool for other purposes due to their ease of acquisition and low dose compared to x-rays[7,8]. This work has highlighted that in some cases they can be suitable for MR screening and that with sufficient training and dedicated experience, at least some of the missed implants could be detected. Future work in this area should compare CT scout performance to that of the recommended imaging modality, plain film x-rays. Furthermore, the dose of CT scouts should also be evaluated in comparison to the cumulative dose of a series of plain film x-rays.Acknowledgements

This work was carried out at, and supported by, the Department of Neuroradiology at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The authors would like to thank Sithabile Mahlokozera for her help with this study. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.References

1. Mervak B.M, Wilson SB, Handly BD, et al. MRI in acute appendicitis. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2019; 50:1367–1376

2. Seif, M., Curt, A., Thompson, A.J., et al. Quantitative MRI of rostral spinal cord and brain regions is predictive of functional recovery in acute spinal cord injury. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2018; 20: 556–563.

3. Nurminen J, Velhonoja J, Heikkinen J, et al. Emergency neck MRI: feasibility and diagnostic accuracy in cases of neck infection. Acta Radiologica. 2020; 62(6): 735-742

4. Safety Guidelines for Magnetic Resonance Imaging Equipment in Clinical Use, 2021. UK: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency.

5. ACR Manual on MR Safety, 2020. Virginia, USA: American College of Radiologists Committee on MR Safety

6. Gohmann R.F, Hecker F, Uschner, D, et al. Body Pushers: Low-Dose CT, Always the Best Choice? A Study of the Diagnostic Performance of CT Scout View. Open Journal of Radiology. 2017; 7: 112-120

7. Can TS, Yilmaz BK and Ozdemir S. Using CT scout view to scan illicit drug carriers may reduce radiation exposure. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2021; 81.

8. Ziegeler E, Grimm JM, Wirth S, et al. Computed tomography scout views vs. conventional radiography in body-packers – Delineation of body-packs and radiation dose in a porcine model. European Journal of Radiology. 2012; 81(12): 3883-3889

9. Cho S, Jo W, Jo Y, et al. Bench-top Comparison of Physical Properties of 4 Commercially-Available Self-Expanding Intracranial Stents. Neurointervention. 2017; 12(1): 31–39.

10. Al Suwaidi J, Berger PB and Holmes DR. Coronary Artery Stents. Clinical Cardiology. 2000;284(14):1828–1836.

Figures

3a) CT scout image containing the missed carotid stent. 3b) Carotid stent correctly identified.

The carotid stent in Fig. 3a, although visible, is partially obscured by superimposed anatomy.

4a) CT scout image containing a frenum piercing. 4b) Unknown metallic foreign body.

The frenum piercing (4a) is a rare implant and at the edge of the field of view in an image already containing multiple implants. The foreign body (4b) is visible even against superimposed anatomy on the anterior-posterior projection.

5a) CT scout image containing Vagal Nerve Stimulator (VNS). 5b) Pacemaker.

Both active implants were recognised as such, but the VNS was incorrectly identified as a pacemaker. The VNS (5a) can be distinguished from a pacemaker (5b) by the metallic attachments to the vagus nerve (orange arrow). Any active implant poses a high risk in MRI and would need to be investigated thoroughly before proceeding.