Fetal Neuroimaging in Practice: An evidence - based rationale to analysis of fetal malformations producing vermis rotation and posterior fossa expansion

1Monash Health, Australia, 2Department of Imaging, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

Synopsis

Risk - stratification of fetuses with an upwardly rotated cerebellar vermis will improve prenatal counselling.

1.Measurement of the cerebellar vermis to determine "hypoplasia". The vermis is reduced in size (in the range of 1 – 2 standard deviations below the gestational age mean for AP and CC diameter) in many cases of PBPC, is unassociated with persistence of URCV, is seen in cases where URCV resolves (Pinto et a, Conte et all) and failed to distinguish arbitrarily – labelled fetal MRI cases of PBPC and DWM in fetuses <23.1/40 (Nagaraj). Futhermore, compression of the vermis by the PBPC can mimic vermis hypoplasia. Using the term “vermis hypoplasia” or IIVH to describe normal mild reduction of vermis biometry in PBPC / URCV can create confusion with other prognostically adverse causes true vermis hypoplasia.

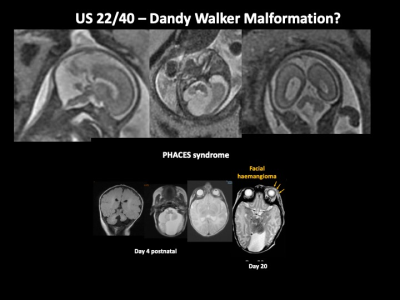

2.The “cerebellar tail sign (CTS)” as an indicator of Dandy – Walker malformation and by association, a more adverse prognosis. The cerebellar tail is is a specific dysplasia of the nodular lobule of the posterior cerebellum. The CTS on fetal MRI and ultrasound is a thick linear, posteriorly projecting extension of the midline posterior vermis. This now pathologically-proven (Haldipur et al) posterior vermian dysplasia with an imaging correlate has been demonstrated in human cases labelled DWM and a mouse model of DWM. Using the CTS to distinguish PBPC and DWM is problematic. Its clinical significance in the absence of classical DWM remains unclear due to lack of outcome data for fetuses with CTS and inclusion of cases in Haldipur et al's series whose imaging meets criteria for PBPC / URCV . Many fetal MRI case reports show examples of CTS followed derotation of the URCV to a normal appearance later (Chapman et al, Pinto et al, Conte et al) or persistent CTS with normal neurodevelopment (Guibaud et al).

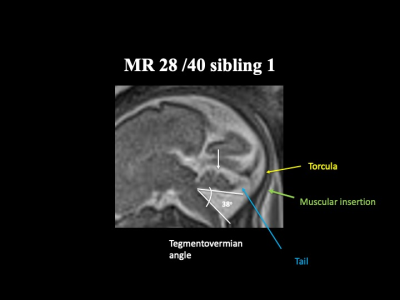

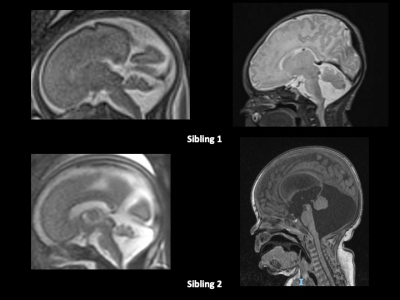

3.Measurement of the tegmentovermian angle and cisterna magna depth to predict derotation and neurodevelopmental outcome. Conte et al found the combination of 2 or more of: tegmentovermian angle >23 degrees, cisterna magna AP diameter >9mm and tail sign predicted failure of vermis derotation with sensitivity of 84.2% specificity of 80.8% and NPV of 87.5% (95% CI, 70.9–95.2%) in 45 fetuses with mean gestation of 21.5 weeks. However, the neurodevelopmental consequence, if any, of failure of derotation is unclear and not examined in this study.

4.Coexistent brainstem and supratentorial malformations OR microarray, chromosomal + /- sonographic or fetal MRI evidence of a syndrome, present in up to 25% and 50% of fetuses with PBPC, respectively (D’Antonio et al. Behram et al) are prognostically important.

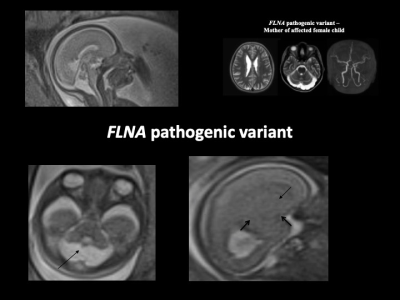

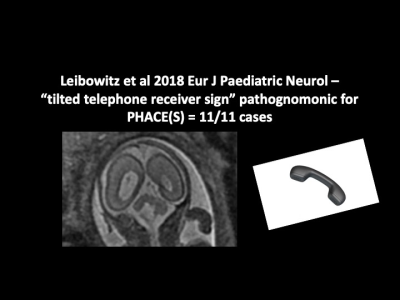

6. Subependymal nodular heterotopia and the “tilted telephone receiver sign” in association with mega cisterna magna and DWM, respectively, may point to FLNA pathogenic variant and PHACES and should be specifically sought in every case.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

Behram M, Oğlak SC, Ölmez F, Gedik Özköse Z, Süzen Çaypınar S, Başkıran Y, Sezer S, Erdoğan K, Yüksel MA, Özdemir İ. Blake's pouch cyst: Prenatal diagnosis and management. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Mar 12;18(1):44-49. doi: 10.4274/tjod.galenos.2020.21703. PMID: 33715332; PMCID: PMC7962159.

Bernardo, V. Vinci, M. Saldari, F.Servadei, E. Silvestri, A. Giancotti, C.Aliberti, M.G. Porpora, F. Triulzi, G.Rizzo, et al. Dandy-Walker Malformation: is the ‘tail sign’ the key sign?Prenat. Diagn., 35 (2015), pp. 1358-1364 Bolduc ME, Du Plessis AJ, Sullivan N, et al. Spectrum of neurodevelopmental disabilities in children with cerebellar malformations. Dev Med Child Neurol2011; 53: 409–16.

Chapman T, Kapur RP (2018) Cerebellar Vermian Dysplasia: The Tale of the Tail. J Pediatr Neurol Neurosci 2(1):17-22.

D’Antonio F, Khalil A, Garel C, Pilu G, Rizzo G, Lerman-Sagie T, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of isolated posterior fossa malformations on prenatal ultrasound imaging (part 1): nomenclature, diagnostic accuracy and associated anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47:690-7.

Gandolfi Colleoni G, Contro E, Carletti A, Ghi T, Campobasso G, Rembouskos G, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of fetal posterior fossa fluid collections. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:625–631.doi: 10.1002/uog.11071.

Goergen SK. What's in a name? Everything. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec;48(6):803-804.

Guibaud L, Larroque A, Ville D, Sanlaville D, Till M, Gaucherand P, Pracros JP, des Portes V. Prenatal diagnosis of ‘isolated’ Dandy–Walker malformation: imaging findings and prenatal counselling. Prenat Diagn 2012; 32: 185–193.

Haldipur, P., Bernardo, S., Aldinger, K.A. et al. Evidence of disrupted rhombic lip development in the pathogenesis of Dandy–Walker malformation. Acta Neuropathol 142, 761–776 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-021-02355-7

Klein O, Pierre-Kahn A, Boddaert N, et al. Dandy-Walker malformation: prenatal diagnosis and prognosis. Child’s Nerv Syst 2003;19:484– 89.

Paladini D, Quarantelli M, Pastore G, Sorrentino M, Sglavo G, Nappi C.Abnormal or delayed development of the posterior membranous area of the brain: anatomy, ultrasound diagnosis, natural history and outcome of Blake's pouch cyst in the fetus.Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar; 39(3):279-87.

Pinchefsky EF, Accogli A, Shevell MI, Saint-Martin C, Srour M. Developmental outcomes in children with congenital cerebellar malformations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019 Mar;61(3):350-358. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14059. Epub 2018 Oct 15. PMID: 30320441.

Pinto J, Paladini D, Severino M, Morana G, Pais R, Martinetti C, Rossi A. Delayed rotation of the cerebellar vermis: a pitfall in early second-trimester fetal magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;48(1):121-124. doi: 10.1002/uog.15782. Epub 2016 May 30.

Salsi G, Volpe G, Montaguti E, Fanelli T, Toni F, Maffei M, Votino C, Pompilii E, Pilu G, Volpe P: Isolated Upward Rotation of the Fetal Cerebellar Vermis (Blake’s Pouch Cyst) Is a Normal Variant: An Analysis of 111 Cases. Fetal Diagn Ther 2021;48:485-492. doi: 10.1159/000516807

Figures