Classification of Vascular Anomalies & Role of MRI

1Sick Kids Toronto, Canada

Synopsis

Vascular anomalies are common in children. Using the classification proposed by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA), they can be categorized into two large groups: vascular tumors and vascular malformations. MRI is used in a minority of cases but provides useful information for diagnosis, treatment monitoring and assessment of associated anomalies, especially overgrowth. MRI relies on the use of T1 and T2 (usually with fat suppression) sequences as well as contrast-enhanced angiography and contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1 sequences. Correlation with clinical information is crucial for appropriate interpretation of MRI findings.

Vascular tumors refer to lesions that show endothelial hyperplasia and growth and include benign lesions such as infantile and congenital hemangiomas, locally aggressive or borderline lesions such as kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, and rare malignant lesions such as angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Vascular malformations refer to congenital lesions characterized by abnormal morphogenesis of specific vessels but with normal endothelial cell turnover and only weak endothelial cell proliferation [2]. These can be categorized into simple (capillary, venous, lymphatic or arteriovenous), combined, of major named vessels, associated with other anomalies (commonly overgrowth), and provisionally unclassified.

The diagnosis of vascular anomalies can often be made on clinical grounds or with the help of ultrasound [3, 4]. MRI is often requested when ultrasound has not provided diagnosis or has not shown the full extent of the lesion, when assessing large and deep lesions, when the lesion is associated with other anomalies such as overgrowth, and as a baseline or follow-up to monitor treatment response. It is important to emphasize that the interpretation of imaging findings has always to be correlated with the clinical findings and the radiologist should make an effort to have all relevant clinical information at the time of doing MRI.

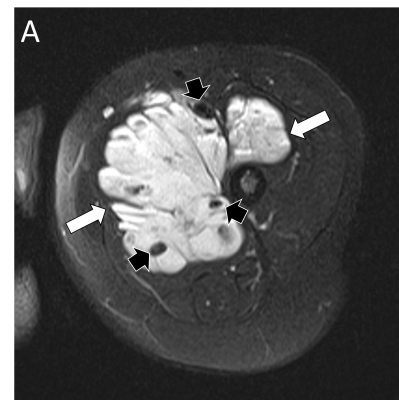

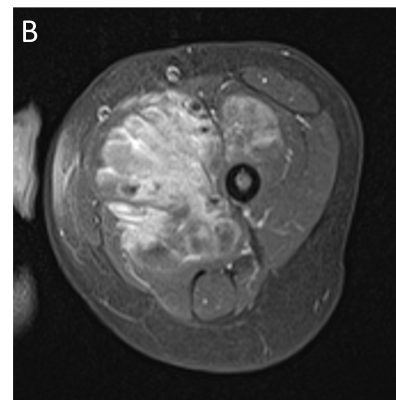

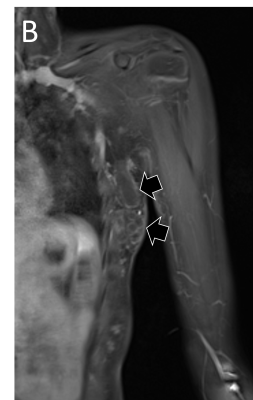

MRI is performed using the smallest coil that includes the entire lesion with acquisition in at least two orthogonal planes. A combination of sequences is routinely used including spin echo T1 and fat-suppressed T2 (or STIR) [5]. Gradient-echo sequences may also be used to facilitate identification of hemosiderin, particularly when assessing venous malformations involving a joint [6], and to detect intralesional high-flow vessels. The examination is followed by contrast-enhanced MR angiography ideally using a 3D time-resolved technique that allows better differentiation of arterial from venous flow and detection of early venous filling [7]. The exam then concludes with at least one fat-suppressed T1 sequence that allows assessment of delayed enhancement and may provide further anatomical detail. Diffusion-weighted MRI may be added when the differential diagnosis includes a malignant neoplasm.

This presentation will illustrate characteristic MRI findings that allow the diagnosis of the most relevant pediatric vascular anomalies using the ISSVA classification.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies ©2018 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies Available at "issva.org/classification". Accessed January 27, 2022

2. Amaral JG, Lara-Corrales L. Vascular anomalies: clinical perspectives. Pediatr Radiol 2022; 52:249–261

3. Johnson C, Navarro OM. Clinical and sonographic features of pediatric soft-tissue vascular anomalies part 1: classification, sonographic approach and vascular tumors. Pediatr Radiol 2017; 47:1184–1195

4. Johnson C, Navarro OM. Clinical and sonographic features of pediatric soft-tissue vascular anomalies part 2: vascular malformations. Pediatr Radiol 2017; 47:1196–1208

5. Navarro OM. Magnetic resonance imaging of pediatric soft-tissue vascular anomalies. Pediatr Radiol 2016; 46:891–901

6. Mattila KA, Aronniemi J, Salminen P et al. Intra-articular venous malformation of the knee in children: magnetic resonance imaging findings and significance of synovial involvement. Pediatr Radiol 2020; 50:509–515

7. Hammer S, Uller W, Manger F et al. Time-resolved magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) at 3.0 Tesla for evaluation of hemodynamic characteristics of vascular malformations: description of distinct subgroups. Eur Radiol 2017; 27:296–305

Figures