4853

Dynamic Changes in the Pituitary Gland and Brain Stiffness with Treatment of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2Opthalmology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 3Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Morphological changes in the pituitary gland and brain stiffness in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) are not well understood. We evaluated the difference in pituitary height and regional brain stiffness between IIH patients and controls and how these metrics change following acute and chronic treatment. The pituitary gland is smaller in IIH patients than controls and increases in size after chronic, but not acute, treatment of raised intracranial pressure. IIH patients have a different pattern of brain stiffness than controls, including stiffer occipital lobes. Following chronic treatment, the stiffness pattern becomes more like controls, though occipital stiffness does not significantly change.

Introduction

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) in the absence of central nervous system pathology. Empty sella is a common radiographic feature of IIH, but the dynamic nature of this finding in response to changes in ICP is not well described. A less widely studied feature is brain stiffness, which may be assessed with magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). Based on prior animal models, we hypothesized that brain stiffness is increased in IIH. The goals of this study were to compare pituitary height and brain stiffness between patients with IIH and healthy controls and to evaluate how those metrics change in patients after treatment.Methods

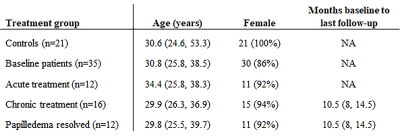

Participants: Patients with diagnoses of IIH and papilledema were recruited from the clinical practice. Age-matched controls were local community members.MRI: Imaging was performed on the Compact 3T system (GE healthcare)[1] using an 8-channel head coil. All patients were imaged at baseline, and subgroups of patients underwent imaging following intervention (large volume, 30 mL) lumbar puncture (LP), medical management, and/or venous sinus stenting. The control group was imaged at one time point. Structural imaging included whole brain T1-weighted imaging performed using a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) acquisition with the following parameters: TR/TE/TI 6.1/2.5/900 ms, flip angle 8°, FOV 160 x 160 mm2, matrix 256 x 256, slice thickness 1.2 mm. MRE was acquired using a flow-compensated, spin-echo, echo-planar imaging pulse sequence with parameters of 60-Hz vibration, TR/TE 3601.2/62.9 ms, flip 90°, FOV 240 x 240 mm2, matrix 72 x 72, and slice thickness 3 mm.

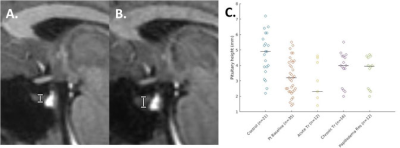

Pituitary height measurement: The pituitary height was measured in the middle third of the gland on the mid-sagittal plane of the MPRAGE acquisition.

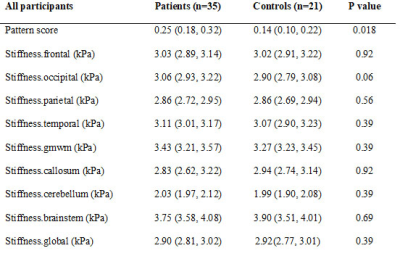

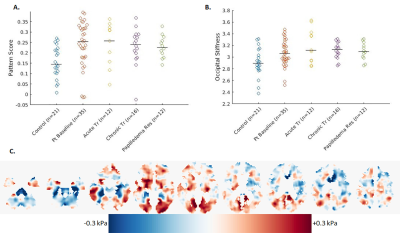

MRE processing and pattern score: A neural network inversion was used to estimate stiffness from displacement data [2]. Voxel-wise modeling of the stiffness maps was used to assess the effect of IIH on mechanical properties. Pattern analysis was performed by computing the correlation between each person's stiffness map and the expected IIH effect using a leave-one-out approach.

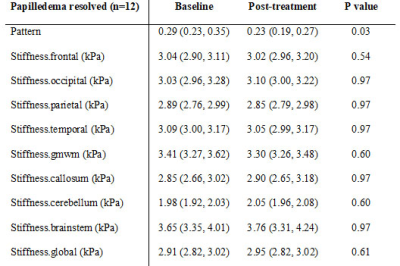

Statistical analysis: We used a linear regression model, adjusted for age and sex, to evaluate for differences in pituitary height, MRE pattern score, and regional stiffness between IIH patients at baseline and controls. Next, we used the Wilcoxon signed rank test to assess for change in imaging metrics between patients at baseline and three treatment groups (1) acute treatment, within 1 day after large volume LP, (2) chronic treatment, at least 6 months after initiation of medication treatment or venous sinus stent placement, and (3) chronic treatment, papilledema resolved or significantly improved (decrease in two Friesen grades). For pituitary height, a one-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test was used as the pituitary was expected to be smaller in IIH and increase after treatment. The p values for regional stiffness were false discovery rate (FDR) corrected [3] to account for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as pFDR < 0.05.

Results

The 35 IIH patients and 21 healthy controls are detailed in Table 1. At baseline, the pituitary height was smaller in IIH patients than controls (median (interquartile range) = 3.2(2.3, 4.3) mm vs. 4.9 (3.8, 6.1) mm, p < 0.001). The pituitary gland increased in height with chronic treatment in IIH patients (baseline 3.2 (2.6, 4.5) mm vs post-treatment 4.0 (2.5, 4.6) mm, p=0.01), though did not change after LP (baseline 2.4 (1.9, 4.0) mm vs post-LP 2.3 (1.7, 4.2) mm) (Figure 1).On MRE, the median stiffness pattern score (0.25 (0.18, 0.32) vs 0.14 (0.10, 0.22), p = 0.02) and the occipital lobe stiffness (3.06 (2.93, 3.22) kPa vs 2.90 (2.79, 3.08) kPa , p = 0.007) were greater in IIH patients than controls (Figure 2, Table 2). After chronic treatment, the pattern score decreased and reached statistical significance in the subgroup of patients in whom papilledema resolved (0.23 (0.19, 0.27) vs (0.29, 0.23, 0.35), p = 0.03) (Table 3). The occipital region stiffness did not significantly change after chronic treatment (3.13 (3.02, 3.22) kPa vs (3.08 (2.97, 3.30) kPa, p = 0.47). In other regions, there were variable, non-statistically significant differences in stiffness between patients and controls and among patients following acute versus chronic treatment.

Discussion

As demonstrated in prior studies, we found the pituitary height was smaller in IIH patients compared to controls [4],[5]. The increase in pituitary height following chronic but not acute treatment suggests that the gland takes time to rebound from the effects of raised ICP. MRE showed a difference in stiffness pattern in IIH patients versus controls, and the decrease in pattern score after chronic treatment suggests that the changes in regional stiffness may in part be due to the presence of increased ICP and reverse after treatment. The lack of change in occipital lobe stiffness after treatment and resolution of papilledema indicates that increased occipital stiffness may be a predisposing factor to IIH rather than a consequence.Conclusion

The pituitary gland is small in IIH and increases in size after chronic treatment. Regional brain stiffness is different in IIH patients versus controls. Whether regional stiffness changes predispose to or result from IIH remains unclear and may be evaluated in future studies.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] T. K. F. Foo et al., “Lightweight, compact, and high-performance 3T MR system for imaging the brain and extremities,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 80, no. 5, pp. 2232–2245, 2018, doi: 10.1002/mrm.27175.

[2] M. Murphy et al., “Identification of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus by Disease-Specific Patterns of Brain Stiffness and Damping Ratio,” Investigative Radiology, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 200–208, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000630.

[3] “fdr_bh.” https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/27418-fdr_bh (accessed Oct. 28, 2021).

[4] R. Agid, R. I. Farb, R. A. Willinsky, D. J. Mikulis, and G. Tomlinson, “Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the validity of cross-sectional neuroimaging signs,” Neuroradiology, vol. 48, no. 8, pp. 521–527, Aug. 2006, doi: 10.1007/s00234-006-0095-y.

[5] M. C. Brodsky and M. Vaphiades, “Magnetic resonance imaging in pseudotumor cerebri,” Ophthalmology, vol. 105, no. 9, pp. 1686–1693, Sep. 1998, doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99039-X.

Figures