3035

Stressful life events associate with adolescent depression through dysfunction of frontoparietal network1Huaxi MR Research Center (HMRRC), Department of Radiology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, 2Department of Radiology, the Third Hospital of Mianyang, Sichuan Mental Health Center, Mianyang, China, Mianyang, China, 3Department of Psychiatry, the Third Hospital of Mianyang, Sichuan Mental Health Center, China, Mianyang, China

Synopsis

The current study investigate functional network alterations in adolescent MDD using the clustering analysis. We found that adolescents with MDD showed decreased connectivity between the frontoparietal network (FPN) and other networks relative to HC. The global connectivity strength of FPN was negatively correlated with the punishment and academic pressure factors, and mediated the association between these two stressors and depression. Our findings suggest that punishment and academic pressure may contribute to the development of depression in adolescence through dysfunction of the FPN, which may promote future prevention of adolescent MDD.

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical developmental period which encompasses many significant changes, including brain growth, biological and physical changes of puberty, and major social role transitions1. These changes make some adolescents more susceptible to the effects of psychosocial stressors and are vulnerable to developing depression2.Stressful life events are salient risk factors for MDD in adolescence3. The association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms or disorders has been consistently reported in both cross-sectional4 and longitudinal studies5. Neuroimaging studies found that the ways early life stress affects the brain networks were similar to those of adult depression6. However, how the life stress influence the adolescent brain and involve the development of adolescent depression remain unclear.

In this study, we aim to investigate functional network alterations in adolescents with MDD and explore the associations among these functional properties of networks, stressful life events and adolescent depression.

Methods

Participants and MRI Data AcquisitionWe recruited 68 adolescents with MDD and 43 healthy controls (HC) aged from 11 to 18 years old from The Third People's Hospital of Mianyang, Sichuan. All participants were scanned using a 3.0T MRI system with a twenty-channel phased-array head coil. The MR data consisted of resting-state EPI images and T1-weighted anatomical images.

Clinical measurement

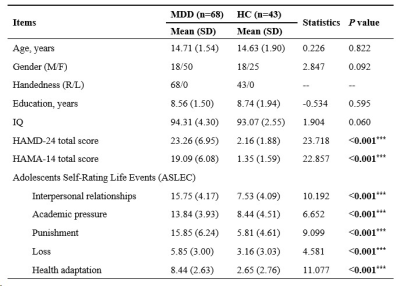

The Hamilton depression scale 24 item (HAMD-24) and Hamilton Anxiety scale 14 item (HAMA-14) were applied to assess the symptoms severity of depression and anxiety of all adolescents. Recent negative life events were measured using the Adolescents Self-Rating Life Events Checklist (ASLEC), which was utilized to assess the frequency of stressful life events and stress response intensity over the previous 12 months.

Functional connectivity analysis

The k-means clustering (k ranged from 2 to 22) was performed to identify functional networks in MDD and HC groups, respectively. To evaluate the stability of the clustering solutions, the Dice’s coefficient was computed for each number of clusters. Then we calculated the weighted degree centrality (DC) for each network to characterize the global connectivity strength of the networks. The weighted degree centrality measures the sum of weights or strength from edges (i.e., the Pearson correlation coefficient) connecting to a network.

Statistical analysis

The differences of the degree centrality of networks between MDD and HC groups were investigated using the ANCOVA with age, gender, IQ and mean FD as covariates. We further investigated the relationships between DC of group differences and HAMD total scores and factors in ASLEC using partial correlation analysis. Finally, the mediation analysis was performed to explore the mediation role of DC alterations in the associations between factors in ASLEC and depression diagnosis. The p < 0.05 was set as significance threshold and the Bonferroni correction was used to correct multiple comparison.

Results

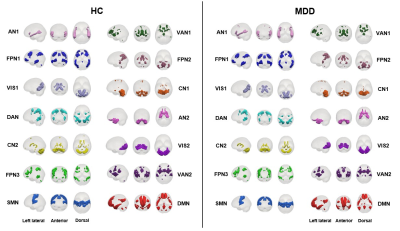

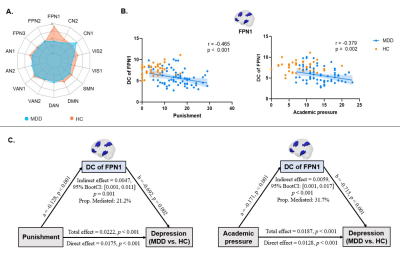

The demographic and clinical information of MDD patients and HC were presented in Table 1. MDD adolescents showed significantly higher HAMD and HAMD scores, and higher scores of all factors in ASLEC compared with HC.The clustering analysis identified fourteen stable and detailed GM functional networks for both MDD and HC groups (Figure 1). Comparing to HC, adolescents with MDD showed significantly lower weighted degree centrality of the first subnetwork of the frontoparietal network (FPN1). The DC of FPN1 was negatively correlated with the punishment and academic pressure factors of the ASLEC in the MDD group, and mediated the association between these two stressors and depression after controlled the effects of the age, gender, IQ and mean FD (Figure 2).

Discussion & Conclusion

Adolescents with MDD showed global hypoconnectivity of the FPN, a network involved in cognitive control and emotion regulation7. This result was consistent with previous findings that functional connectivity abnormalities in adolescent MDD were mainly focused on the cognitive control network8.Interestingly, we found that the global hypoconnectivity of FPN was correlated with increased punishment and academic stress, and mediated the associations between these two stressors and depression. These findings suggest that punishment and academic pressure may contribute to the development of depression in adolescence through dysfunction of frontoparietal network, which may promote future prevention of adolescent MDD.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by grants from 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC21041) and Clinical and Translational Research Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2021-I2M-C&T-B-097).References

1. Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D et al. The age of adolescence. The Lancet. Child & adolescent health. 2018;2(3):223–228.

2. Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS et al. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379:1056–1067.

3. Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2299-2312.

4. Mileviciute I, Trujillo J, Gray M et al. The role of explanatory style and negative life events in depression: A cross-sectional study with youth from a North American plains reservation. American Indian and Alaska Native Health Research. 2016;20(3):42–58.

5. Asselmann E, Wittchen H-U, Lieb R, et al. Danger and loss events and the incidence of anxiety and depressive disorders: a prospective-longitudinal community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine, 2015;45:153–163.

6. Gong Q, He Y. Depression, neuroimaging and connectomics: a selective overview. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(3):223-235.

7. Marek S, Dosenbach NUF. The frontoparietal network: function, electrophysiology, and importance of individual precision mapping. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(2):133-140.

8. Tang S, Lu L, Zhang L, et al. Abnormal amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in adults and adolescents with major depressive disorder: A comparative meta-analysis. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:436-445.

Figures