2828

The potential value of whole-body MRI for the rheumatologist’s assessment and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients1Centre for Adolescent Rheumatology Versus Arthritis, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for Medical Imaging, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Rheumatology, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Sheffield, United Kingdom, 4Sheffield Children's NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, United Kingdom, 5Department of Rheumatology, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 6Department of Radiology, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

The impact of musculoskeletal inflammation detected by whole-body MRI (WBMRI) in adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) on rheumatologists’ clinical decisions was investigated. Anonymised clinical information collected for 30 patients before undergoing research WBMRI scans was examined by two rheumatologists who recorded independently their disease activity ratings, investigations, and treatment plans before and after reviewing the WBMRI reports. WBMRI findings changed rheumatologists’ disease activity ratings in half the patients and treatment plan in one-third, approximately. WBMRI detected inflammation in sites recommended for regional imaging pre WBMRI in less than half of cases and in other sites in more than one-half.

Introduction

The ability of whole-body MRI (WBMRI) to detect synovitis in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) has been demonstrated previously1. The impact of WBMRI findings on clinical management of JIA patients has not been explored. Our aim was to assess the potential for WBMRI to modify rheumatologists’ impression of disease activity and subsequent treatment decisions in adolescent patients with JIA.Methods

Two rheumatology consultants, working in different tertiary hospitals in the United Kingdom and experienced in managing people with JIA, reviewed anonymised clinical data from a cohort of patients with JIA (aged 15-24), not under their care.The cohort consisted of the first 30 JIA patients who participated in a prospective research study that involved undergoing a research WBMRI scan after being clinically assessed by a senior rheumatology fellow. Patients were eligible for recruitment irrespective of their disease activity. The WBMRI protocol included post-contrast mDixon images and the scans were reported by an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist, blinded to clinical information, for the presence of musculoskeletal inflammation.

The rheumatology assessment was in 2 stages; the first without and the second with the WBMRI findings. For each stage the clinical findings and patient-reported outcomes recorded before the WBMRI, the patients’ present and past treatments, imaging and laboratory results were included in the clinical summaries given to each rheumatologist.

Stage 1: The rheumatologists independently

i) rated their impression of disease activity (See Table 1);

ii) documented their recommendations for any further imaging;

iii) described their proposed plan for any treatment changes.

If imaging was advised, they were asked to specify the imaging method, site, and treatment considerations depending on inflammation detection.

Stage 2: With the addition of the WBMRI result the rheumatologists independently

i) re-rated disease activity

ii) updated their imaging and treatment suggestions with knowledge of WBMRI findings.

The responses without and with the WBMRI findings were compared for each consultant and between them.

Results

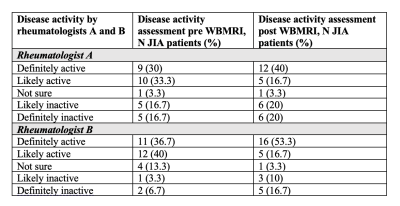

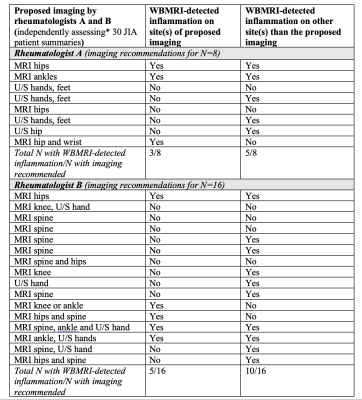

Disease activity ratings were changed after reviewing the WBMRI reports in 16/30 (53.3%) and 17/30 patients (56.7%) by the rheumatologist A and B respectively. The activity category (‘active’ to ‘inactive’ or vice versa) changed in 7/16 (43.8%) and 4/17 (23.5%) cases, respectively. The certainty in the activity status increased for both rating clinicians (from ‘likely’ to ‘definitely’ in the same category or from ‘not sure’ to any other category) in 7/16 (43.8%) and 11/17 (64.7%) cases, respectively, whilst decreased for both in 2 cases. Disease activity assessments with and without WBMRI, are summarised in Table 1. The inter-rater agreement without and with WBMRI regarding disease activity (active/inactive) was 84.00% and 82.1% respectively.Imaging was recommended at stage 1 in 8/30 (26.7%) cases by the rheumatologist A and in 16/30 (53.3%) by the rheumatologist B. These were comprised of MRI scans in 4/8 and 15/16 cases and of ultrasound in 4/8 and 5/16 cases, respectively. The selected sites for imaging and the presence or absence of WBMRI-detected inflammation in those or other areas are listed in Table 2. Inflammation was detected in other sites and not in those selected for imaging by rheumatologist A and B in 3/8 and 7/16 cases, respectively.

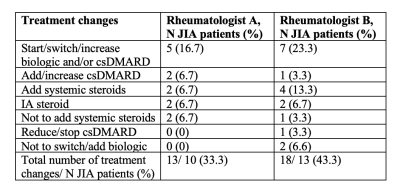

The frequency of treatment modifications from the first to the second response for both rheumatologists are summarised in Table 3. The inter-rater agreement regarding the intention to change treatment (yes/no) improved from 63.3% without WBMRI to 83.3% with WBMRI. The change in the treatment plan according to rheumatologist A and B included the initiation or change of biologic treatment in 5/10 and 7/13 patients.

Discussion

WBMRI scan findings changed the rheumatologists’ impression or level of certainty regarding disease activity in about half the patients and treatment plan in about one-third, mostly resulting in treatment escalation. It is unknown whether increasing treatments to target subclinical inflammation on imaging leads to clinical benefits for patients with JIA, even though joint inflammation can be a precursor of joint damage. In this study, treatment decisions were not made solely based on imaging, but after correlation with the clinical information provided, such as patients’ symptoms. On the other hand, although these were decisions pertaining to actual patients, they were not made in real-life, jointly by the patient and treating doctor, and relied on assessments performed by another physician.In 62.5% cases WBMRI-detected inflammation at sites that would not have been shown by the additional imaging recommended by rheumatologists A and B at stage 1. This highlights an advantage of WBMRI over regional imaging with potential impact on treatment decisions. However, the rate of inflammation detection by the proposed imaging methods could have been different from the observed due to the varying inherent sensitivities of imaging techniques.

Conclusion

This small study shows WBMRI has potential to alter assessment of disease activity and treatment plans in patients with JIA. This requires validation with a larger more diverse study population. Moreover, research studies are needed to investigate if there are long-term benefits to JIA patients from the early identification and treatment of subclinical inflammation with the use of WBMRI.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Action Medical Research and Humanimal Trust [GN2697 to MHC], British Society of Rheumatology [179978 to VC] and by the Centre of Excellence (Centre for Adolescent Rheumatology Versus Arthritis) grant (21593). TJPB is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). MAHC, DS and CC are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) University College London Hospitals (UCLH ) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

References

1.Choida V, Ciurtin C, Bray TJP, Sen D, Fisher C, Leandro M, Hall-Craggs MA. O14 Frequency and site of clinically unsuspected synovitis on whole-body MRI in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Rheumatology 2021 April; 60(1)Figures

Table 1. Disease activity ratings pre and post WBMRI results for 30 JIA patients by two rheumatologists. The rheumatologists reviewed independently clinical summaries for each patient and rated the disease activity before and after receiving the WBMRI reports.

JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, N: number, WBMRI: whole-body MRI

Table 2. WBMRI-detected inflammation in JIA patients, selected for regional imaging assessment by two rheumatologists, in relation to the recommended site(s) for imaging

JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, N: number of patients, U/S: ultrasound, WBMRI: whole-body MRI, * unaware of WBMRI findings

Table 3. Treatment changes post WBMRI from pre WBMRI assessment in 30 JIA patients by two rheumatologists. The rheumatologists made independent treatment recommendations for each patient based on clinical summaries before and after receiving the WBMRI reports.

JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, IA: intra-articular, csDMARD: conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, N: number, WBMRI: whole-body MRI