2766

Liver response to fasting and isocaloric high-carbohydrate refeeding in lean and obese women1MR unit, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague, Czech Republic, 2Department of Internal Medicine, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, University Hospital Královské Vinohrady, Prague, Czech Republic, 3Department of Pathophysiology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, 4Centre of Experimental Medicine, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague, Czech Republic

Synopsis

Our MRS and MRI study investigates the liver response to two days of fasting followed by two days of isocaloric high carbohydrate refeeding in lean and obese women. Hepatic fat content increased after fasting in lean women whereas it did not change in obese women. The tendency to lose or accumulate fat during fasting could be related to the overall initial hepatic fat content. Moreover, liver volume significantly decreased and increased during fasting and refeeding, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease affects more than 25% of the adult population and closely relates to the obesity and diabetes pandemic. Although the mechanisms leading to fat accumulation in the liver have been extensively studied, there is still a lack of studies investigating the effects of short-term nutritional or other interventions on changes in hepatic fat content (HFC). Interventions designed to improve metabolic health in obese and diabetic patients frequently include various forms of fasting. Nevertheless, two-day fasting has been shown to increase HFC in lean healthy men1 whereas in healthy women no changes of HFC could be detected2. The impact of varying adiposity on HFC in response to fasting and subsequent refeeding has not been studied yet.METHODS

The healthy women, 10 lean (BMI = 21.5±1.6 kg/m2, age = 35.8±7.0 years) and 11 obese (BMI = 34.5±4.7 kg/m2, age = 36.6±7.1 years), underwent three MR sessions and blood samplings (before fasting - day 0; after 48h of fasting - day 2; and after 48h of isocaloric high-carbohydrate refeeding following in total 60h of fasting - day 5).MR examination was performed on 3T MR system VIDA (Siemens, Germany) equipped with 30-channel surface and spine coil.

The study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval of local ethics committee.

Hepatic fat fraction (FF)

FF was measured by LiverLab engine consisted of T1 VIBE e-Dixon and single voxel spectroscopic technique HISTO (STEAM sequence with parameters: TR = 3000 ms, 5 spectra during one breath-hold with TE = 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 ms, voxel size 40x30x25 mm). Automatic and manual shimming were combined to reach water line width below 50 Hz. Volume of interest position in liver segments V/VIII was carefully controlled during follow-up examinations.

Hepatic fat volume (HFV)

To calculate HFV, the FF value from the HISTO protocol was first recalculated to the hepatic fat content (HFC) according to Longo3 and then HFC was multiplied by total liver volume (TLV). The TLV value was obtained from the automatic segmentation routine which processes images from e-Dixon VIBE sequence.

Statistical evaluation

Results were statistically evaluated by Two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test (HFC, TLV data were log-transformed for statistical test). P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

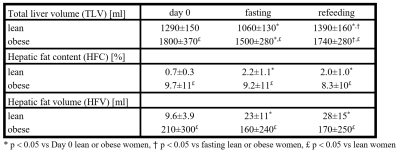

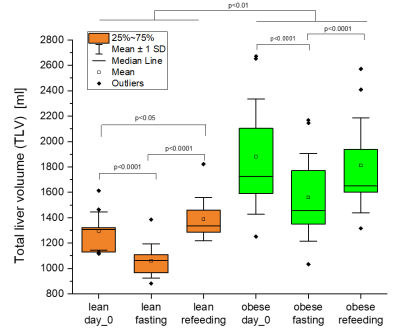

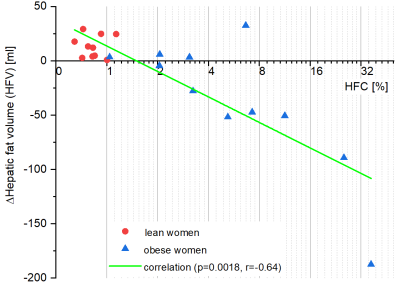

All measured parameters (TLV, HFC and HFV) were different between obese and lean group at all intervention time points.TLV decreased by 230±60 ml (-18% of baseline TLV) in the lean group and by 320±140 ml (-17% of baseline TLV) in the obese group in response to fasting; after refeeding period, it increased above the basal values in lean women, while in obese returned to the basal levels, see Table 1 and Figure 1.

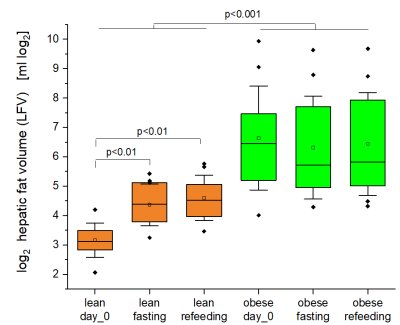

HFC increased by 1.5±1 % (p<0.001, 200% of baseline HFC) and HFV also increased by 13.3±9.8 ml (p<0.01, 140% of baseline HFV) during fasting and remained increased even after refeeding only in the lean group, see Table 1 and Figure 2. A negative correlation between baseline log2 HFC and change of HFV during fasting period was found (p=0.0018, r=-0.64, see Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

In lean women, lipids accumulated in the liver during fasting whereas no changes in HFC in response to the intervention were observed in obese women. The 2-day refeeding following the fasting did not influence neither HFC nor HFV in both groups. Our findings in lean women are consistent with Moller´s finding1 that HFC increases in lean men after 36h of fasting but they are in contrast to those of Browning2 who did not see any significant increase in liver steatosis in fasting women. However, that study included both lean and obese women (BMI in the range of 22-32 kg/m2), which prevented the deciphering of the adiposity impact on the variables under the study.We were interested in which factor is related to fat accumulation in the liver during fasting, and we found that the change in HFV is inversely proportional to baseline HFC (see Figure 3).

We also addressed the question whether changes in TLV relates to changes in HFC. The decrease of liver volume during fasting in lean women cannot be explained by changes in liver fat that even increases in this group. It is likely due to complete depletion of glycogen stores after 2-day fasting4,5. On the contrary, in obese subjects with hepatic steatosis the changes in HFV might modestly contribute to the decrease in liver volume – the change of HFV negatively correlates with HFC (see Figure 3).

CONCLUSION

We found that hepatic fat increased in lean women after 48 hours of fasting in contrast to obese women where no significant change was found. 48h refeeding was unable to induce return of hepatic fat content to basal levels.Acknowledgements

Supported by Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, grant numbers: NU20J-01-00005 and DRO („Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine – IKEM, IN 00023001“).References

1. Moller L, et al. Fasting in healthy subjects is associated with intrahepatic accumulation of lipids as assessed by 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Sci. 2008;114:547-552.

2. Browning JD, et al. The effect of short-term fasting on liver and skeletal muscle lipid, glucose, and energy metabolism in healthy women and men. Lipid Res. 2012;53(3):577–586.

3. Longo R, et al. Proton MR spectroscopy in quantitative in vivo determination of fat content in human liver steatosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 1995;5(3):281-285.

4. Wahren J, Ekberg K. Splanchnic regulation of glucose production. Ann Rev Nutr. 2007;27:329-345.

5. Nilsson LH. Liver Glycogen Content in Man in the Postabsorptive State. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1973;32(4):317-323.

Figures