1689

Portable, Low-Field MRI for Evaluation of the Knee Joint1Department of Diagnostic, Molecular and Interventional Radiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States, 2BioMedical Engineering and Imaging Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States, 3Hyperfine, Guilford, CT, United States

Synopsis

In this work, we present results of knee imaging using a portable, point-of-care MRI system in healthy subjects and subjects with knee pathology. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported results for knee imaging using the portable Swoop MRI system, a portable 0.064 T MRI scanner. The low-field images show good performance in visualizing the knee joint, and there was not a significant difference in the readers’ ability to evaluate the anatomic structures.

Introduction

MRI has been accepted as the gold standard tool for non-invasive evaluation of acute and chronic knee pathology1,2. However, the costs for current knee MRI exams using a clinical scanner at 1.5 T or 3 T remain high. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, the waiting time for a patient to get an MRI exam can range from two to four weeks in the US, although the US has the second highest number of MRI scanners per million people3. This challenge has prevented timely and efficient exams, particularly for patients with acute diseases. The development of low-field, portable and thus more accessible MRI scanners has gained substantial interest in recent years, and this holds great potential to change the landscape of where and how MRI imaging can be performed. For example, a recent study has shown that a portable, low-field (0.064 T) MRI scanner can be directly put in the intensive care unit for neuroimaging4. For knee pathology, it would also be highly desired to have such MRI scanners in outpatient clinics, where typically only radiographs are available, which provide very limited diagnostic information. The accessibility of portable MRI and its superior soft-tissue contrast would enable improved point-of-care evaluation of trauma or other suspected pathologies such as tendonous or ligamentous injury5. In this work, we present our first results of knee imaging using a portable, point-of-care MRI system in healthy subjects and subjects with knee pathology.Methods

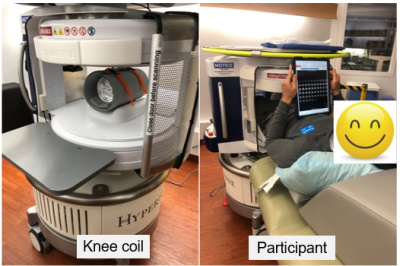

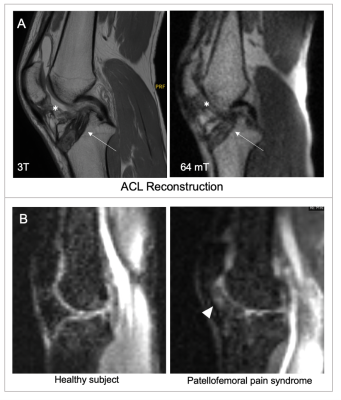

This study was performed on a prototype portable Swoop MR system (Hyperfine, Guilford, CT) equipped with an integrated radio frequency (RF) transmit coil and an 8-channel RF receive-only flexible knee coil for the lower extremity (Figure 1A). The Swoop MRI scanner has a field strength of 0.064 T with gradient strengths of 26 mT/m (z-axis) and 25 mT/m (x- and y-axis). All imaging was performed under a protocol approved by the local institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained prior to imaging. Nine healthy subjects (8 male, 1 female; age range 27-34 years) and two subjects with history of knee pathology (one 28-year-old male subject with history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; one 26-year-old male subject with a clinical diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome) were included. Figure 1B shows a representative scanning position for a subject, with which the subject can have the knee MRI scanning while using their electronic devices. The imaging protocol consisted of two steady-state GRE (PSIF) acquisitions on coronal and sagittal planes, respectively, and a fast spin echo-based fluid-sensitive short tau inversion recovery (STIR) acquisition on sagittal plane. Total scan time was approximately 30 minutes. Spatial resolution was 1.5x1.5x3.0 mm for all the acquisitions. Imaging parameters for the PSIF imaging were: TR=11-12ms, TE=8-9ms, and 8 averages. For the STIR imaging, the TR/TE=1300/4.25ms without average. All images were pooled for blind assessment by three musculoskeletal fellowship trained radiologists. Specifically, the readers scored the diagnostic quality for identifying seven major tendons and ligaments of the knee based on an ordinal scale (Table 1), which ranged from zero to two through four depending on number of insertion sites about the knee joint. The quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) were assessed on the sagittal PSIF images, and the iliotibial band (IT band), lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) were assessed on the coronal PSIF images. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the inter-reader variability.Results

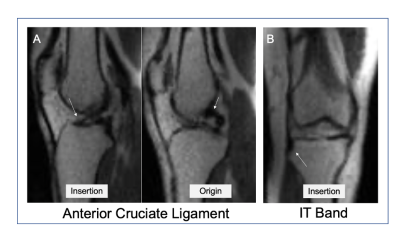

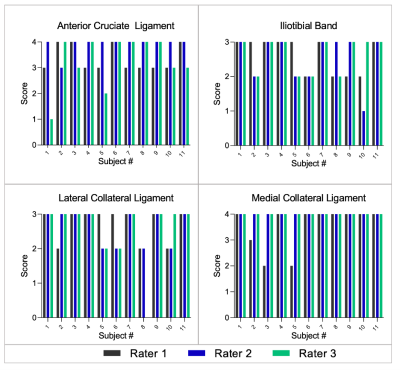

Imaging was completed successfully in all the subjects. Figure 2A shows a representative sagittal PSIF image identifying the ACL origin and insertion, with clear ability to trace fibers throughout entire course (Score =4). Figure 2B shows a representative coronal PSIF image identifying the insertion site of the IT band on the tibia (Score =2). Of note, the origin of the IT band is the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata, which is outside of the field of view (FOV). All raters assigned the highest score for the quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon and PCL (2,3,4, respectively). Each rater’s score for the ACL, IT band, LCL, and MCL is shown in Figure 3. Based on the ANOVA analysis, there was no significant difference in the raters' ability to identify the ACL(P = 0.1), IT band(P = 0.9), LCL(P= 0.8) and MCL(0.1). Overall, these findings demonstrate that the portable Swoop MRI can adequately detect major tendons and ligaments in the knee. Figure 4 shows imaging findings in the two subjects with knee pathology.Discussion and Conclusion

In this work, we have demonstrated the feasibility of knee imaging using a portable 0.064 T MRI system. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported results for knee imaging using the portable Swoop MRI system. The low-field images show good performance in visualizing the knee joint, and there was not a significant difference in the readers’ evaluation. These initial results indicate that point-of-care knee MRI has a wide range of potential applicability, including rapid and timely diagnosis of different acute knee diseases. However, future work will need to include larger study groups and direct comparison with corresponding high-field imaging to fully evaluate its diagnostic performance.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. ACR Appropriateness Criteria®Acute Trauma to the Knee. In:2019:https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69419/Narrative.

2. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Chronic Knee Pain. In:2018:https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69432/Narrative.

3. Number of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units in selected countries as of 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/282401/density-of-magnetic-resonance-imaging-units-by-country/. Accessed November 9, 2021.

4. Mazurek MH, Cahn BA, Yuen MM, et al. Portable, bedside, low-field magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of intracerebral hemorrhage. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5119.

5. Geethanath S, Vaughan JT, Jr. Accessible magnetic resonance imaging: A review. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49(7):e65-e77.

Figures