0613

Resting-state functional connectivity reductions in the cingulate gyrus in HIV exposed uninfected neonates1Biomedical Engineering Research Centre, Division of Biomedical Engineering, Department of Human Biology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 3Family Centre for Research with Ubuntu, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health and Tygerberg Children’s Hospital, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 4Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, United States, 5Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 6Department of Statistical Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 7A.A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 8Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 9Cape Universities Body Imaging Centre, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Synopsis

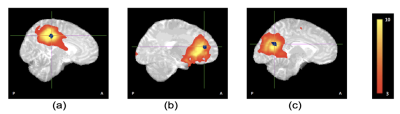

Aggressive combination antiretroviral treatment in pregnancy has significantly reduced new perinatal HIV infections giving rise to a growing population of HIV exposed uninfected (HEU) children. Children who are HEU demonstrate neurodevelopmental delay compared to their HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) peers. We examined resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) in neonates exposed to HIV and ART in utero and perinatally using resting-state fMRI. Ten standard resting-state networks were identified from independent component analysis. Voxelwise group comparison between neonates who are HEU and HUU revealed localized RSFC reductions in the cingulate gyrus within 3 networks: medial somatosensory, and anterior and posterior default mode networks.

Introduction

Resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) is used to identify brain regions that are temporally correlated when the subject is not performing any explicit task1. Aggressive promotion of combination antiretroviral treatment (ART) in pregnancy has significantly reduced new perinatal HIV infections giving rise to a growing population of HIV exposed uninfected (HEU) children2,3. While children who are HEU perform better than their HIV-infected counterparts, they continue to demonstrate neurodevelopmental delay compared to children who are HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU)4, especially in resource-poor settings. Here we examined resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) in neonates exposed to HIV and ART in utero and perinatally.Methods

Mothers with and without HIV were recruited at <31 weeks gestation from an antenatal clinic at the Michael Mapongwana Community Health Centre (MMCHC) in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. High-resolution T1-weighted structural and rs-fMRI data were acquired on a 3T Skyra MRI (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at the Cape Universities Body Imaging Centre (CUBIC) in 106 neonates born to these women at mean gestational age (GA) 41.4±1.0 weeks. Of these, 70 infants were born to mothers with HIV (HEU) and 36 to mothers who were HIV uninfected (HUU). None of the infants was HIV infected. Rs-fMRI data were acquired using an echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence (resolution = 2.5x2.5x2.5 mm3, FOV = 190x190x120 mm3, 48 slices, 270 volumes, TR = 1500 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle 65°, slice acceleration 2). T1-weighted structural images were acquired in the sagittal orientation using a multiecho MPRAGE sequence (resolution = 1.0x1.0x1.0 mm3, FOV = 192x192x144 mm3, 144 slices, TR = 2540 ms, TI = 1450 ms, TEs = 1.69/3.55/5.41/7.27 ms, flip angle 7°)5. Rs-fMRI data were analysed using afni_proc.py in AFNI6, including signal stabilization, motion correction, normalization, blurring, regression, and band passing. All images were registered to an infant standard space7. Group independent component analysis (ICA) and dual regression were performed in FSL. Randomise in FSL was used to find clusters showing differences in RSFC between neonates in the HEU and HUU groups. AFNI’s 3dFWHMx and 3dClustSim were used to calculate the minimum volume of clusters within each network mask for significance at voxelwise p < 0.001 and alpha < 0.05 using the new “mixed ACF” (autocorrelation function) methodology to account for non-Gaussianity in the spatial noise distribution8.Results

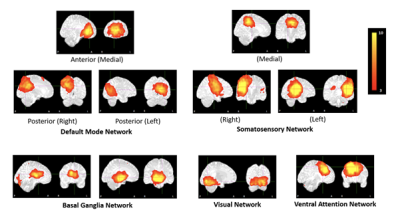

Ten standard resting-state networks (RSNs) were identified from 20 group components (Fig 1). Voxelwise group comparison revealed localized RSFC reductions in neonates who are HEU compared to those who are HUU in the cingulate gyrus (CG) within 3 networks: medial somatosensory network, anterior and posterior default mode network (DMN) (Fig 2).Conclusion

Notably, connectivity within the DMN was not fully integrated as is often seen in young individuals9. The somatosensory network was split into left, right, and medial parts, and the basal ganglia network was split into 2 medial parts. Connectivity deficits in the CG in neonates who are HEU suggest that the maternal immune response may indirectly impact fetal brain development10. The CG, which is a component of the limbic system lying on the medial aspect of the cerebral hemisphere, may be particularly vulnerable due to its proximity to perivascular spaces through which pro-inflammatory cytokines from the mother's immune response may penetrate the fetal brain.Acknowledgements

This study was funded by NRF/DSI South African Research Chairs Initiative, NIH grants R01HD085813 and R01HD093578, an equipment grant from the UCT University Research Committee, NRF Thuthuka, and Harry Crossley Clinical Research Fellowship. We thank the mothers and babies for their participation, our research staff, and the CUBIC radiographers.References

1. Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, et al. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541.

2. Moodley T, Moodley D, Sebitloane M, et al. Improved pregnancy outcomes with increasing antiretroviral coverage in South Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16,35–45.

3. Zash R, Souda S, Chen JY, et al. Reassuring birth outcomes with tenofovir/emtricitabine/efavirenz used for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71:428–36.

4. Laughton B, Cornell M, Kidd M et al. Five year neurodevelopment outcomes of perinatally HIV‐infected children on early limited or deferred continuous antiretroviral therapy. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018; 21(5):e25106.

5. van der Kouwe AJ, Benner T, Salat DH, et al. Brain morphometry with multiecho MPRAGE. NeuroImage. 2008;40:559–569.

6. Cox RW. AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173.

7. Shi F, Yap PT, Wu G, et al. Infant Brain Atlases from Neonates to 1- and 2-Year-Olds. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(4): e18746.

8. Cox RW, Chen G, Glen DR et al. FMRI clustering in AFNI: False positive rates redux. Brain Connect. 2017;7(3):152-171.

9. de Bie H, Boersma M, Adriaanse S, et al. Resting-state networks in awake five-to eight-year old children. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:1189–1201.

10. Wedderburn CJ, Yeung S, Rehman AM, et al. Neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected children in South Africa: outcomes from an observational birth cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(11): 803–813.

Figures