2964

Regional Variations in T2 Relaxations Times in the Hip Cartilage of Female Water Polo Players and Synchronized Swimmers1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Radiology, Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 4Centre for Hip Health and Mobility, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Synopsis

Water polo players and synchronized swimmers have been found to have an increased prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement morphology compared to the general population. In this study, we used quantitative MRI to identify regional patterns in the composition of hip cartilage of Division 1 female water polo players and synchronized swimmers. Variations in T2 relaxation times showed regional hip cartilage differences between the water polo players and synchronized swimmers and within the sub-regions of the synchronized swimmer’s hip cartilage. This study suggests that microstructural differences are present in the various regions of these athletes’ hip cartilage.

Introduction

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a syndrome diagnosed by extra bone growth in the hip joint that causes cam/pincer morphologies, hip pain, and evidence of contact between the femoral head-neck region and the acetabulum. Sporting activity during adolescence has been strongly associated with the development of cam morphology in athletes1. Water polo and synchronized swimming require extensive eggbeater kicking, a continuous rotational motion in the hip joint, and these athletes have been found to have a higher incidence of cam morphology than the general population2. Quantitative MRI methods offer a way to non-invasively study early changes in hip joint cartilage microstructure3 that may be associated with FAI morphologies. This study hypothesizes that quantitative MRI will identify different regional T2 patterns in the hip cartilage of female water polo players and synchronized swimmers.Methods

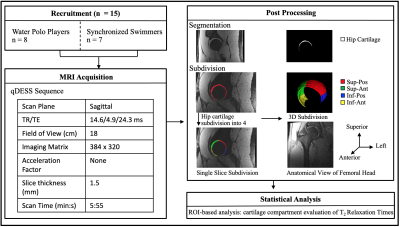

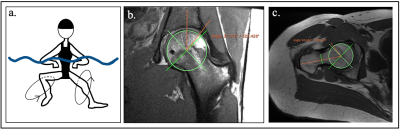

This Institutional Review Board approved study enrolled fifteen National Collegiate Athletic Association Division 1 athletes (20.5±1.4 yrs.), including 8 water polo players and 7 synchronized swimmers, with informed consent. Athletes were excluded if they had previous hip surgery. Each athlete underwent a non-contrast unilateral hip MRI scan on their right hip using a whole-body 3 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with a 16-channel flexible phased-array-receive-only coil (NeoCoil, Pewaukee, WI, USA). A quantitative double-echo in steady-state (qDESS) sequence (5 minutes/hip) was acquired to calculate T2 relaxation times3. Hip cartilage was manually segmented to define the region of interest for T2 maps. The segmentation included both acetabular and femoral cartilage as a single unit due to the close proximity of the two cartilage surfaces4. We manually subdivided the segmentation, using a circle fitted around the femoral head, into four quadrants: superior-posterior, superior-anterior, inferior-posterior, and inferior-anterior (Figure 1). The four quadrants were created using vertical and horizontal planes parallel to the coronal and axial imaging planes. A Generalized Linear Model with a Bonferroni correction and α=0.05 was used to test for T2 differences associated with sport and hip cartilage subregions. A Pearson correlation was used to compare T2 relaxation times with previously determined cam and pincer morphology measures and with labral tears2. Cam and pincer morphologies are clinically defined respectively by the alpha angle (> 55°) and lateral central edge angle (LCEA) (> 39°)(Figure 2b,c). Labral tears were scored using the Scoring Hip Osteoarthritis Using MRI (SHOMRI)5 semi-quantitative grading scale.Results

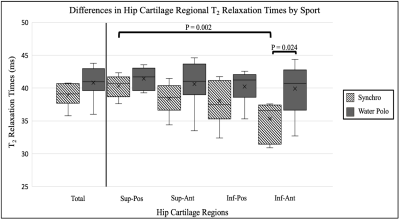

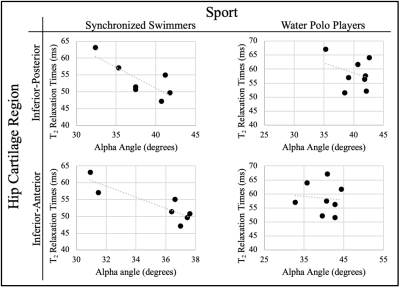

In the inferior-anterior region of the hip joint cartilage, water polo players had significantly higher T2 relaxation times than the synchronized swimmers (39.9±2.9 vs 35.3±2.9, p=0.024). Among all athletes, T2 relaxation times were significantly higher in the superior-posterior region than the inferior-anterior region (p=0.010). In the inferior-posterior and inferior-anterior regions of the synchronized swimmers’ hip cartilage, there were significantly higher T2 relaxation times in swimmers without labral tears (n=4) than swimmers with clinically identified labral tears (n=3) (p=0.026, p=0.035). Average T2 relaxation times for synchronized swimmers and water polo players in the total hip cartilage and four subregions are summarized in Figure 3. In the synchronized swimmers, there was a strong negative correlation between T2 relaxation times in the inferior-posterior and inferior-anterior regions of their right hip cartilage and alpha angle (R=-0.790, p=0.035 and R=-0.876, p=0.010) (Figure 4).Discussion

In the synchronized swimmers, T2 relaxation times were significantly higher in the superior-posterior region of the hip cartilage than in the inferior-anterior region. There were no significant regional differences in the water polo players’ cartilage. The sub-regional analysis between sports showed significantly different T2 relaxation times in the inferior-anterior region of the hip joint cartilage between water polo players and synchronized swimmers, suggesting possible regional differences in cartilage composition between these two groups. These observed differences could be due to previously observed differences in the percentage of time that these athletes use an eggbeater kick with water polo players using it for a greater percentage of the time, about 55% of games, and synchronized swimmers for only 40% of their total performance routines6.Unexpectedly, we saw a negative correlation between inferior hip cartilage T2 relaxation times vs labral tears and increasing alpha angles. The eggbeater motion (Figure 2a) that water polo players and synchronized swimmers perform while treading water could be placing increased rotational stress on the superior region of the joint (area with the highest average T2 relaxation times), possibly leading to a lighter load or recovery occurring in the inferior region of the hip. With FAI, inferior cartilage usually has the least contact with the acetabulum and the superior-anterior region is typically where most of the impingement occurs7. A previous regional analysis of hip cartilage in FAI-patients compared to healthy controls also found significantly increased T2 relaxation times in the superior-anterior region of the hip joint cartilage8. This may explain the negative correlation between inferior hip cartilage T2 relaxation times and labral tears/alpha angles, but further analysis is needed.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates that quantitative MRI can detect regional differences in water polo players’ and synchronized swimmers’ hip cartilage composition and could be a useful tool in a longitudinal study of these athletes’ cartilage health. Knowledge of injury patterns and early detection of possible cartilage damage can help inform strategies for keeping athletes healthy when they present with hip pain.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Major Grant from the Stanford University Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education as part of the Human Biology Honors Program. Support also came from GE Healthcare, and the National Institutes of Health (EB002524, AR06206).References

1. Palmer, A., Fernquest, S., Gimpel, M., et al. 2018. Physical activity during adolescence and the development of cam morphology: a cross-sectional cohort study of 210 individuals. British Journal of Sports Medicine 52(9), pp. 601–610.

2. Langner, J.L., Black, M.S., MacKay, J.W., et al. 2020. The prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement anatomy in Division 1 aquatic athletes who tread water. Journal of hip preservation surgery 7(2), pp. 233–241.

3. Sveinsson, B., Chaudhari, A.S., Gold, G.E. and Hargreaves, B.A. 2017. A simple analytic method for estimating T2 in the knee from DESS. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 38, pp. 63–70.

4. Nishii, T., Nakanishi, K., Sugano, N., Masuhara, K., Ohzono, K. and Ochi, T. 1998. Articular cartilage evaluation in osteoarthritis of the hip with MR imaging under continuous leg traction. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 16(8), pp. 871–875.

5. Neumann, J., Zhang, A.L., Schwaiger, B.J., et al. 2019. Validation of scoring hip osteoarthritis with MRI (SHOMRI) scores using hip arthroscopy as a standard of reference. European Radiology 29(2), pp. 578–587.

6. Vathagavorakul, R., Gonjo, T. and Homma, M. 2020. The effect of experience in movement coordination with music on polyrhythmic production: Comparison between artistic swimmers and water polo players during eggbeater kick performance. Plos One 15(8), p. e0238197.9.

7. Fow, J.E. 2013. Hip Arthroscopy. In: Rehabilitation for the postsurgical orthopedic patient. Elsevier, pp. 382–387.

8. Subburaj, K., Valentinitsch, A., Dillon, A.B., et al. 2013. Regional variations in MR relaxation of hip joint cartilage in subjects with and without femoralacetabular impingement. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 31(7), pp. 1129–1136.

Figures