2797

3.0 T MRI detects brain ventricle oscillations in patients with clinically-isolated syndrome1Berlin Ultrahigh Field Facility (B.U.F.F.), Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association, Berlin, Germany, 2NeuroCure Clinical Research Center, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Synopsis

We used clinical high resolution 3T MRI to investigate brain ventricle changes over time in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) who are at the early stages of disease, which may eventually become multiple sclerosis. While most patients showed an overall increase in ventricle volume, 23% also showed contractions greater than the range of variation in healthy subjects, even over a period of years. Patients with contracting ventricles were significantly younger than those without. This suggests that, in addition to neurodegeneration, other processes are implicated that lead to a transient enlargement of the ventricles, which then later resolves.

Introduction

Inflammatory processes during autoimmune disease have the potential to impact on the fluid balance in the brain. We previously reported an enlargement of the brain ventricles prior to disease onset in the animal model of neuroinflammation, experimental autoimmune encephalitis, which normalized upon remission of clinical signs.1,2 We then showed that some patients with established relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) also showed transient enlargement of their ventricles.2 Those patients with contractions in their ventricle volumes had lower disease severity and shorter disease duration compared to patients without contractions, suggesting that they were at an earlier phase of their disease. Here we used clinical high resolution MRI data obtained at 3.0 T to investigate brain ventricle changes in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) who are, by definition, at the early stages of disease, which may or may not eventually lead to a diagnosis of MS.Methods

We analysed a cohort of patients who were examined at multiple time points between 2012 and 2019 in our clinic at the NeuroCure Clinical Research Center of the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin: n=39, 74.4% female; mean age 34.3±8.8 years (range 20-56 years). This data was obtained from routine clinical practice, with variable timing of follow-up scans performed according to the clinical needs of individual patients. Diagnosis of CIS and conversion to MS was according to the 2017 revised McDonald criteria.3 Patients underwent neurological examination to obtain the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores. Anatomical MRI scans were acquired on a 3T MR scanner (MAGNETOM Tim Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence: (TR/TE/TI=1900/2.55/900 ms, FOV=256×256 mm2, matrix 256x256x176 slices, 1×1×1 mm3 resolution). MRI scans were analysed using FreeSurfer v6.04 using the recon -all function to obtain absolute values of ventricle volumes. Data from CIS patients was compared with our previously published analysis of a cohort of RRMS patients.2 A cohort of healthy individuals who underwent multiple sequential MRI scans served as the control group.5Results

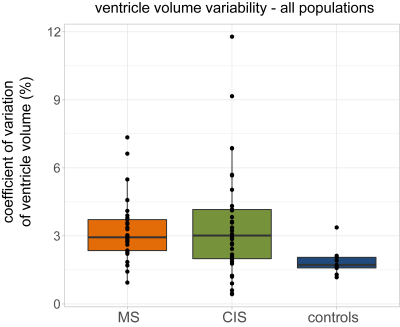

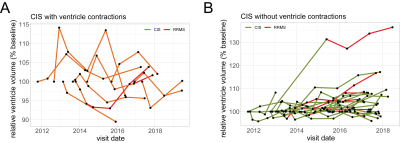

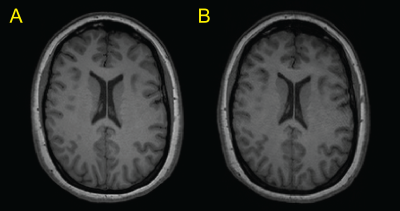

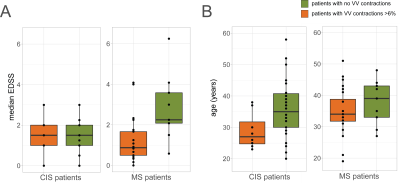

Considering our previous observations, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) for CIS patients, and compared this to the RRMS patient cohort and a healthy control group (Figure 1).2 Unlike the monthly observations of our previous RRMS cohort, the time scale between observations in the current CIS cohort spans over months and years. Nevertheless, CIS patients also showed significantly greater variance in their ventricle volumes, compared to control subjects (Figure 1). We found that 9/39 patients (23%) showed contractions in their ventricle volumes >6%, which we previously identified as the threshold of variation in healthy subjects (Figure 2A). The majority of CIS patients showed an overall trend of increasing ventricle volume, consistent with a process of neurodegeneration over months and years (Figure 2B). There was no difference in the proportion of patients who converted to MS (15/39 in total) between the contracting and non-contracting patients. Scans of an exemplary patient are shown in Figure 3. Between the first scan acquired 76 days after the initial clinical event (Figure 3A) and the follow-up scan 2.5 years later (Figure 3B) there was an 11% reduction in total ventricular volume. CIS patients with and without ventricle contractions had equivalent levels of disease severity, as reflected in the median EDSS throughout the study period (Figure 4A). This was similar to the disease severity of RRMS patients with ventricle contractions, which we previously showed was significantly lower than that of patients without contractions (Figure 4A). While the age of CIS patients in our cohort ranged over 36 years, the patients with ventricle contractions >6% were significantly younger than those without. Ages of RRMS patients with ventricle contraction trended lower, but this was not significant (Figure 4B).Conclusions

CIS patients are by definition at the early phase of their neurological disease. We show that even over a period of years, brain ventricle volumes in some CIS patients do not increase unidirectionally. This suggests that, in addition to processes of neurodegeneration, other processes that may be disease-related lead to a transient enlargement of the ventricles (beyond the range of normal variation), which then later resolves. CIS patients with ventricle contractions may represent a distinct subset of patients that would require further in-depth investigations. RRMS patients with ventricle contractions not only had lower disease severity, but also had shorter disease duration2, suggesting that those patients were at an earlier stage of their disease. Together with the fact that CIS patients with ventricle contractions were significantly younger than those without, this raises the possibility that volatility in ventricle volume (or the lack thereof) may be an indicator of “brain age”, which in MS is known to be older than “chronological age”.7,8 This speculation will require validation in larger datasets.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Lepore, S., et al. Enlargement of cerebral ventricles as an early indicator of encephalomyelitis. PloS one 8, e72841 (2013).

2. Millward, J.M., et al. Transient enlargement of brain ventricles during relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. JCI insight 5(2020).

3. Thompson, A.J., et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. The Lancet. Neurology 17, 162-173 (2018).

4. Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 62, 774-781 (2012).

5. Filevich, E., et al. Day2day: investigating daily variability of magnetic resonance imaging measures over half a year. BMC neuroscience 18, 65 (2017).

6. Cole, J.H., et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis with the Brain-Age Paradigm. Annals of neurology 88, 93-105 (2020).

7. Hogestol, E.A., et al. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal MRI Brain Scans Reveal Accelerated Brain Aging in Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in neurology 10, 450 (2019).

Figures