1062

Central vein sign occurrence on FLAIR* in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus patients1Department of radiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 2Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

Synopsis

The central vein sign (CVS) is an imaging biomarker useful in multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis and to differentiate MS from other autoimmune diseases with inflammatory lesions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus with neuropsychiatric events (NP). The prevalence of CVS in SLE patients experiencing NP is unknown. We examined 16 NPSLE patients for presence of CVS using FLAIR* images, generated from FLAIR images acquired at 3T and T2*-weighted images acquired at 7T. Out of 491 white matter lesions, we found 4 confirmed and 1 suspected CVS lesions. Our data suggests that CVS may be present in random occurrence in NPSLE.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic auto-immune disease with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations, including heterogeneous and uncommon neuropsychiatric (NP) syndromes1. NPSLE diagnosis is challenging due to the lack of useful biomarkers, therefore a multi-disciplinary expert consensus is the current standard for diagnosis2. Furthermore, underlying pathogenic mechanisms resulting in pathophysiological changes, which in turn lead to NP symptoms, are not completely understood3. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease that shares some similarities with NPSLE as well as with other autoimmune diseases that can affect the brain, such as Behcet’s disease and Sjogren’s syndrome. Previous studies have shown that a specific perivenular lesion, the central vein sign (CVS), was a suitable marker to distinguish certain MS-related lesions from inflammatory vasculopathies. Despite the usefulness of CVS in MS diagnosis, the specificity of CVS to MS and its prevalence in autoimmune brain diseases with an inflammatory component is still unknown4. The most commonly used imaging tool to visualize CVS in MS is FLAIR*, a merging of the magnitude part of the T2*-weighted image and the FLAIR image5. The aim of our study was to generate a pipeline to generate FLAIR* images based on T2*-weighted images acquired at 7T and FLAIR images acquired at 3T, and to use them to assess the presence of CVS in a cohort of SLE patients experiencing NP events.METHODS

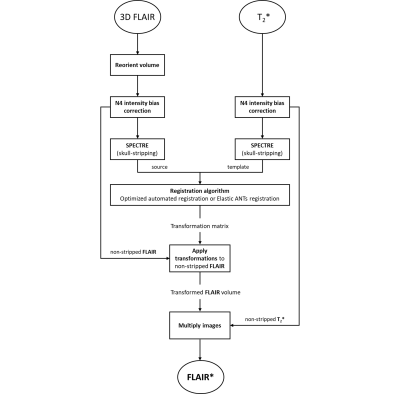

16 NPSLE patients were included in this study. All patients underwent brain MRI (3T and 7T Philips Achieva). The pipeline used to generate FLAIR* images included the use of 3D-FLAIR images acquired at 3T (voxel size = 1.10 × 1.11 × 0.56 mm3; TR/TE/TI = 4800/576/1650 ms) and T2* magnitude images acquired at 7T(3D-GE-EPI; field of view (a-p,f-h,r-l) = 220mm x 125mm x 178mm; voxel size = 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 mm3; EPI factor = 19; TR/TE = 126ms/30ms, flip angle = 20⁰). We used Medical Image Processing, Analysis and Visualization software (MIPAV) to perform linear registration between the two image modalities, Java Imaging Science Toolkit (JIST) to reorient the FLAIR images according to the magnitude of the T2*-weighted image, CBS High Res Brain Processing Tools (CBS Tools) to skull strip both images and Advanced Normalisation Tools (ANTs) for intensity correction N4 and for non-linear registration. The complete pipeline is shown in Figure 1. The MR images were scored by a resident in radiology under supervision of an experienced neuroradiologist who were trained using a set provided by the group that developed the CVS diagnostic procedure at the NIH/NINDS. A central vein sign was defined as an area of high signal intensity with a minimum diameter of 3 mm containing a hypo-intense line or dot in the centre of the lesion present in at least two out of three perpendicular planes5.RESULTS

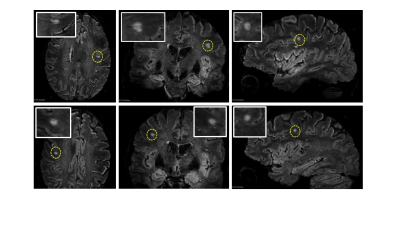

From a total of 491 white matter lesions found in our cohort, 4 confirmed and 1 suspected CVS-positive lesions and 484 CVS-negative lesions were found. Figure 2 demonstrates two CVS lesions detected in one of the NPSLE subjects and displayed on three perpendicular planes across the FLAIR* volumes. The FLAIR* image clearly shows both the lesion and the vein, and in this case the vein and the lesion conform with the definition of CVS.DISCUSSION

At this point, our initial finding is that CVS may not be exclusive to MS, and is also seen in SLE with NP events, an autoimmune vasculopathy. The mechanism for CVS in MS is well documented, whereas the one behind the CVS lesions we observed in NPSLE still needs to be investigated. However, it is likely that brain involvement in SLE might lead to a random distribution of white matter lesions not specifically linked to the penetrating veins, and CVS in SLE might be a random occurrence. It remains to be investigated whether CVS in SLE coincides with NPSLE and whether it is more prevalent in one of the clinical phenotypes of NPSLE, in particular the inflammatory phenotype, where the blood brain barrier may play a role.CONCLUSION

In this work we generated a variant of FLAIR* images obtained using T2* data acquired at 7T and FLAIR images acquired at 3T, and showed that this combination provides excellent contrast between the white matter lesions and the vein, benefitting from the high susceptibility contrast and high spatial resolution attainable at 7T for the T2*-weighted images. To conclude, we generated a pipeline to provide FLAIR* images in order to detect CVS in NPSLE patients. We suggested that the presence of CVS in SLE patients experiencing NP events are random and not specific for NPSLE. This is useful in differentiating MS from NPSLE.Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Pascal Sati for providing us with the training set for identification of CVS.References

1. Ainiala H, Loukkola J, Peltola J, Korpela M, Hietaharju A. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric syndromes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2001 Aug 14;57(3):496-500. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.496. PMID: 11502919.

2. Zirkzee EJ, Steup-Beekman GM, van der Mast RC, Bollen EL, van der Wee NJ, Baptist E, Slee TM, Huisman MV, Middelkoop HA, Luyendijk J, van Buchem MA, Huizinga TW. Prospective study of clinical phenotypes in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and therapy. J Rheumatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):2118-26. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120545. Epub 2012 Sep 15. PMID: 22984275.

3. Magro-Checa C, Steup-Beekman GM, Huizinga TW, van Buchem MA, Ronen I. Laboratory and Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Where Do We Stand, Where To Go? Front Med (Lausanne). 2018 Dec 4;5:340. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00340. PMID: 30564579; PMCID: PMC6288259.

4. Maggi P, Absinta M, Grammatico M, Vuolo L, Emmi G, Carlucci G, Spagni G, Barilaro A, Repice AM, Emmi L, Prisco D, Martinelli V, Scotti R, Sadeghi N, Perrotta G, Sati P, Dachy B, Reich DS, Filippi M, Massacesi L. Central vein sign differentiates Multiple Sclerosis from central nervous system inflammatory vasculopathies. Ann Neurol. 2018 Feb;83(2):283-294. doi: 10.1002/ana.25146. Epub 2018 Feb 15. PMID: 29328521; PMCID: PMC5901412.

5. Sati P, George IC, Shea CD, Gaitán MI, Reich DS. FLAIR*: a combined MR contrast technique for visualizing white matter lesions and parenchymal veins. Radiology. 2012 Dec;265(3):926-32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120208. Epub 2012 Oct 16. PMID: 23074257; PMCID: PMC3504317.

6. Deijns SJ, Broen JCA, Kruyt ND, Schubart CD, Andreoli L, Tincani A, Limper M. The immunologic etiology of psychiatric manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus: A narrative review on the role of the blood brain barrier, antibodies, cytokines and chemokines. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 Aug;19(8):102592. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102592. Epub 2020 Jun 17. PMID: 32561462.