0477

Retrospective Assessment of the Impact of Primary Language Video Instructions on Image Quality of Abdominal MRI

Myles Todd Taffel1, Andrew Rosenkrantz1, Jonathan Foster1, Jay Karajgikar1, Paul Smereka1, Thomas Mulholland1, Hoi Cheng Zhang1, Felicia Calasso1, Rebecca Anthopolos2, Kun Qian2, and Hersh Chandarana1

1Radiology, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY, United States, 2NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY, United States

1Radiology, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY, United States, 2NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Previous work has demonstrated inferior abdominal MRI image quality in non-English speaking patients who require a translator. While a translator may be helpful, they are often interpreting remotely via a telephone and may be unfamiliar with the intricate MRI breathing instructions. As the result of the patient watching an instructional video explaining the MRI procedure in their primary language, image quality improves to match that of studies performed in primary English speaking patients.

Introduction

Respiratory motion has been described as the single greatest technical challenge to overcome for obtaining high quality MRI examinations of the upper abdomen. The current predominant approach for addressing respiratory motion is for the technologist to ask patients to hold their breath during the sequence acquisitions. Specifically, the technologist provides a series of verbal instructions relating to breathing in and out prior to holding the breath for a particular time interval, prior to relaxing and then repeating these steps for the next MRI sequence. For patients for whom English is a second language (ESL), it is standard for the technologists to provide the instructions in the patient’s language. While a translator may assist, they are often interpreting remotely via a telephone and may be unfamiliar with the intricate MRI breathing instructions. Previous work has demonstrated that effective breath-holding instructions are more challenging for non English-speaking patients, which in turn has implications for the quality of such patients’ abdominal imaging examinations.[1] We created videos explaining the upper abdominal MRI examination and its required breathing techniques in Spanish and Mandarin Chinese. This study assessed the subsequent impact of watching these videos on respiratory motion and image quality in ESL patients who required translators.Methods

Beginning in October of 2019, 29 ESL patients who were denoted to need a translator viewed Spanish (duration of 3:00 minutes) or Mandarin Chinese (duration of 2:10 minutes) instructional videos prior to undergoing upper abdominal MRI (“ESL/Video” group). The patients watched the videos in the preparation room while waiting to be placed on the scanner. In addition, the electronic medical record was used to identify 50 ESL patients who underwent abdominal MRI prior to the video implementation (“ESL/No Video” group). A control group of 82 English-speaking patients (“English” group) was matched to the ESL/Video and ESL/No Video groups based on age (in decade), sex, magnet strength, and history of prior MRI. Three abdominal radiologists independently evaluated the anonymized imaging sets using a 1 to 5 Likert scale (with higher score indicating better exam quality) to assess respiratory motion and image quality on turbo-spin echo T2WI and post-contrast T1WI (Figure 1). Groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis tests. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) model was used to pool all reader data, clustering by patient. An adjusted model was computed to adjust for other covariates including age (in decade), sex, magnet strength and prior MRI.Results:

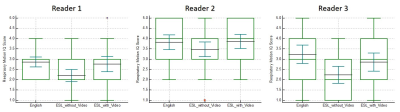

For T2WI respiratory motion, the Likert score distribution of the ESL/No Video group (mean score across readers of 2.6 ± 0.1) was significantly worse when compared to the English group (mean of 3.3 ± 0.2) and the ESL/Video group (mean of 3.2 ± 0.1) (p <.001) (Figure 2). For T2WI overall image quality, the ESL/No Video group (mean of 2.6 ± 0.1) was significantly worse than the English group (3.3 ± 0.1) and the ESL/Video group (3.0 ± 0.2) (p <0.001). For T1WI respiratory motion and T1WI overall image quality, the Likert score distributions were not statistically different between groups (p 0.08-0.68). In the GEE model that accounted for age, sex, magnet strength, and prior MRI, mean T2WI respiratory motion was significantly higher in the English and ESL/Video groups compared to the ESL/No Video group (adjusted p <0.001 and 0.03, respectively). Similarly, the T2WI overall quality was higher in the English and ESL/Video groups than in the ESL/No Video group (adjusted p <.001 and 0.11, respectively). In the GEE model, mean T1WI respiratory motion and T1WI overall quality were not significantly different amongst the groups (adjusted p = 0.42-0.43).Discussion

The US health care system is currently undergoing a transformation with the ultimate goal to equitably deliver high-value, high-quality health care to all patients.[2] This mission extends to radiology. For example, previous work has demonstrated inferior abdominal MRI imaging quality in patients with limited English proficiency.[1] Similar to prior studies, our study showed that the negative effect on image quality was most pronounced on T2WI, a sequence that requires clear communication from the technologist to the patient on breathing timing and respiratory depth. When ESL patients requiring a translator watched instructional videos with detailed instructions prior to abdominal MRI, the quality of the T2WI demonstrated significant improvement compared to a similar cohort that did not watch the video. T2WI quality was not significantly different between ESL/Video group and the English group. The patients watched the videos prior to entering the scanner room, thus minimizing impact on patient workflow.Conclusion

Providing non-English speaking patients an instructional video in their primary language before abdominal MRI is an effective intervention to improve imaging quality.Acknowledgements

References

- Taffel, M.T., et al., Retrospective analysis of the effect of limited english proficiency on abdominal MRI image quality. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2020. 45(9): p. 2895-2901.

- Betancourt, J.R., et al., Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Radiology: A Call to Action. J Am Coll Radiol, 2019. 16(4 Pt B): p. 547-553.

Figures

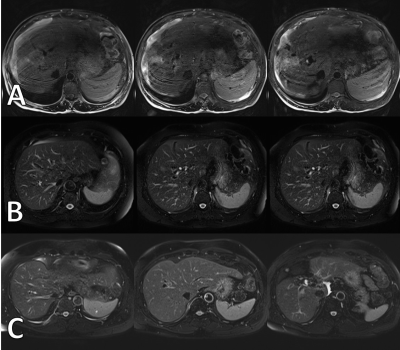

Representative T2-weighted

images for the three groups evaluated by the readers. Patient A (top row) was a 56 YO Spanish-speaking male patient requiring a translator, but did not watch the

instructional video. The respiratory motion

score denoted by each reader for this patient were 1, 1, and 2, respectively. Patient B (middle row) was a 69 YO Spanish-speaking female requiring a translator that watched the video. Reader scores were 4, 4, and 5,

respectively. Patient C (bottom row) was

a 65 YO English-speaking patient that did not watch the video. Reader scores of 4, 4, and 5, respectively.

Box and whisker plots demonstrating mean and

95% confidence interval of the respiratory motion image quality scores for

T2-weighted sequence by each reader. There

was significantly higher respiratory motion image quality score in primary

English speaking patient as well as ESL patients who watched video compared to

ESL patients that did not watch the instructional video.