4854

Validation of USPIO-MRI for detection of lymph node metastases in head and neck cancer: feasibility and workflow.1Radiation Oncology, Radboud university medical centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Radboud university medical centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 3Pathology, Radboud university medical centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 4Oral- and Maxillofacial Surgery and Head and Neck Surgery, Radboud university medical centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 5Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Radboud university medical centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Synopsis

Head and neck cancers have a high propensity to metastasize to the lymph nodes of the neck. Accurate knowledge of this regional nodal status is of great importance for therapy selection and prognosis. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles (Ferumoxtran-10 / Ferrotran®) are a promising contrast agent that can be used to detect nodal metastases with MRI. This study aims to validate USPIO-MRI for the detection of nodal metastases in head and neck cancer patients with histopathology as the reference standard. The workflow and preliminary results in 5 patients are shown in this abstract.

Purpose

The presence of lymph node metastases has a large impact on prognosis and treatment in head and neck cancer. Despite increased spatial resolution of current imaging methods, around 20% of patients with a clinically negative neck will have occult metastases1. Therefore, a large proportion of these patients receive elective treatment of the neck which is associated with substantial acute and late toxicity. If the detection of small lymph node metastases can be improved, elective neck treatment may be avoided in at least a part of the patients resulting in less toxicity and improved quality of life. MRI combined with USPIO contrast agent has proven to be of great value in detecting lymph node metastases in prostate cancer2,3. In this abstract, we demonstrate the study protocol and preliminary results of the USPIO-NECK study which evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of USPIO-MRI for the detection of lymph node metastases in head‐and‐neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with histopathology of resected specimens as a gold standard.Methods

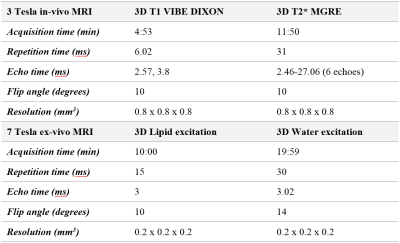

In this single centre prospective pilot study, 25 patients aged ≥18 years with cT0‐4N0‐3M0 SCC of the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx or unknown primary origin who are planned for a neck dissection will be included. Prior to surgery, a dose of 2.6 mg per kilogram bodyweight USPIO was intravenously administered to all patients and 24-36 hours later an MRI examination was performed (3T Magnetom PrismaFit, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany. The USPIO particles accumulate in healthy lymph nodes, suppressing MRI signal on a T2*-weighted multi-gradient echo ironsensitive sequence, whereas metastatic nodes retain MR signal intensity, visualizing lymph node metastases. After surgery and fixation in formalin, an ex-vivo MRI of the neck dissection specimen was acquired on a 7T preclinical MR system (7T, Bruker ClinScan). Both in-vivo and ex-vivo MR parameters are shown in table 1. Suspicious nodes on USPIO-MRI, i.e. nodes retaining MR signal intensity, were identified by two radiologists who are experienced in reading USPIO-MR images and MR images of the neck and made a correlation to the ex-vivo MR images. These ex-vivo MR images were present at the dissection room and guided the pathologist to localize the suspicious node to enable a node-to-node correlation between MRI and histopathology. These nodes were enclosed separately and processed according to the head and neck sentinel node protocol (5 sections every 200 μm, hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry). Other non-suspicious nodes were enclosed per station level, enabling a level-to-level correlation. The histopathologic results served as a reference to validate the USPIO-MR results.Results

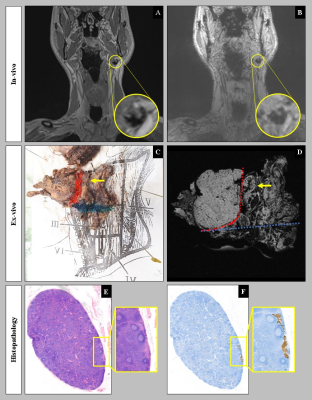

To date, five patients have been included in the study, four with a primary tumour in the oral cavity and one in the oropharynx. Tumour stages varied between II-IVA and both patients with (based on ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration, computed tomography and/or MRI) a clinically positive neck (n = 2) as well as a clinically negative neck (n = 3) were included. On in-vivo MRI, a total of 9 suspicious nodes were identified and enclosed in individual histopathology slices. All suspicious nodes could be matched to ex-vivo MRI and histopathology based on their dimensions and their relation to anatomical landmarks (figure 1). Histopathologic analysis revealed 13 metastatic nodes of the 232 lymph nodes harvested in total. Ex-vivo MRI revealed 271 lymph nodes in total.Discussion

Our preliminary findings demonstrate that visualization of metastatic nodal disease by USPIO-MRI in head-and-neck cancer patients is feasible. Furthermore, the correlation between in-vivo USPIO-MRI and histopathology is possible when guided by ex-vivo MR-images, enabling node-to-node correlation for suspicious nodes. This extra step also warrants that a large proportion (86%) of the nodes found on ex-vivo MR are also found on pathology. The data shows that USPIO particles are distributed to the cervical lymph nodes after intravenous administration. The pattern of uptake can be altered as lymph nodes in this particular region are frequently susceptible to inflammatory changes caused by infections of the upper aerodigestive tract4. Moreover, lymph nodes are punctured during the routine diagnostic tract, potentially disturbing USPIO transport. The relevance of both issues will be further explored while the study progresses.Conclusion

The feasibility of performing USPIO-MRI in head and neck SCC patients is demonstrated by these preliminary findings. Due to the incorporation of the ex-vivo MRI, our workflow enables correlation between in-vivo MR-images and histopathological results on a nodal level which is essential for a future assessment of diagnostic accuracy. A larger patient number is required in order to draw more reliable conclusions on the diagnostic performance of USPIO-MRI on a patient level; our node-to-node correlation allows for analyses on nodal, or at least nodal station level.Acknowledgements

NoneReferences

1. Psychogios G, Mantsopoulos K, Bohr C, et al. Incidence of occult cervical metastasis in head and neck carcinomas: development over time. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(4):384-7.

2. Heesakkers RA, Hovels AM, Jager GJ, et al. MRI with a lymph-node-specific contrast agent as an alternative to CT scan and lymph-node dissection in patients with prostate cancer: a prospective multicohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(9):850-6.

3. Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2491-9.

4. Wensing BM, Deserno WM, de Bondt RB, Marres HA, Merkx MA, Barentsz JO, et al. Diagnostic value of magnetic resonance lymphography in preoperative staging of clinically negative necks in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: a pilot study. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(11):1079-84.

Figures