0228

Influences of Gender, Physical Growth, and Socioeconomic Characteristics on Early Brain Growth in Children from an LMIC Setting.

Sean Deoni1, Aarti Kumar2, Vishwajeet Kumar2, Madhuri Tiwari2, John Spencer3, and Muriel Bruchhage4

1MNCHD&T, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, United States, 2CEL, Lucknow, India, 3University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom, 4Brown University, Providence, RI, United States

1MNCHD&T, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, United States, 2CEL, Lucknow, India, 3University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom, 4Brown University, Providence, RI, United States

Synopsis

Early brain development is influenced by a myriad of environmental and psychosocial exposures that are often amplified in children in low and middle income countries (LMICs). However, few neuroimaging studies have been performed in these settings. Here we report on the first longitudinal neuroimaging study of young children in rural Uttar Pradesh (UP) India, showing the importance of early weight grain and socioeconomic factors on brain growth. We also find significant male-female differences, which may derive from the lesser societal importance of women, including lower education levels, increased malnutrition, and reduced healthcare seeking for girls.

Introduction

Worldwide, more than 250 million children fail to reach their developmental potential with respect to age-appropriate height and/or weight (i.e., are stunted, underweight, and/or wasted)1. Many of these children live in low and middle income settings (LMICs), where they experience adverse health, family, and environmental factors that affect their physical development2. Many of these environmental and psychosocial factors also impact early brain development3,4, placing these children at risk for cognitive deficits and reduced academic success and achievement. Stunted children are less likely to be enrolled in school and are more likely to leave early5; and often have lower overall intelligence quotients (IQ) as well as specific deficits in motor skills, reading, language, reasoning, and social-emotional functioning6. Unfortunately, no longitudinal neuroimaging study has investigated the impact of these specific family and socioeconomic factors on measures of brain growth in children in these settings, which may underlie and precede these later cognitive and academic concerns.Methods

497 longitudinal brain imaging scans were acquired of 156 children (76 female) in Uttar Pradesh (UP), India, on a Philips Achieva 3T MRI scanner equipped with 12-channel head RF array. Children enrolled at ~6, 9, 12 or 15 months of age, and followed until they were 18, 21, 24, or 27 months, with imaging performed every 6 months. T1w anatomical IR-SPGR were acquired, as well as anthropometry, socioeconomic, and demographic data for each child. For volumetric analysis, whole-brain white and gray matter (WM and GM), and regional thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and caudate nucleus volumes were calculated7,8. Mixed effects models were used to calculate individual trajectories of brain development and physical growth (linear growth and weight gain). Mean male and female brain growth trajectories, normalized for child head circumference were also calculated. And models were used to systematically investigate the impact of gender, height and weight for age (HAZ and WAZ), family income, family size, maternal education, use of a flush or open pit toilet, and electricity access on patterns of brain growth.Results

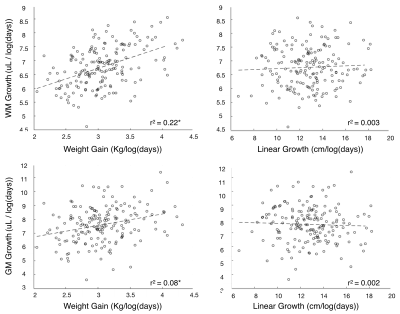

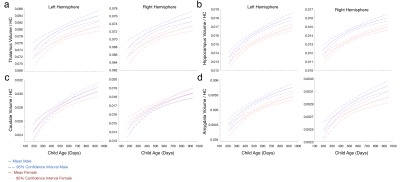

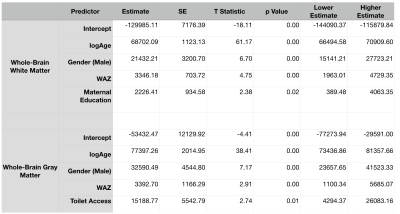

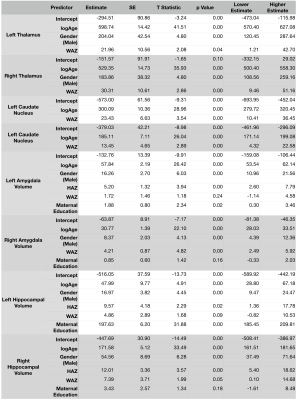

There were no significant male-female group differences in child health indicators, such as birth weight (p=0.43), gestation weeks completed (p=0.67), stunting or wasting occurrence (p=0.26 and 0.07), parent age at child birth (p>0.8), parent education levels (p>0.25), family caste (p=0.64) or Kuppuswamy SES score (p=0.8). From the individual measures of weight gain, linear growth, and brain volume development (Fig, 1), we found significant associations between rate of brain growth and child weight gain for white and gray matter (WM: r2=0.22, p<0.00001 ; GM: r2=0.08, p=0.003 ) but not linear growth rate (WM: r2=0.003, p=0.5; GM: r2=0.002, p=0.57 ). Individual and group mean male and female WM and GM growth trajectories (Fig. 2) reveal a significant male-female difference in growth rate and total volume present at 6m and persisting throughout childhood even when controlling for child head size. These results are mirrored on a regional level (Fig. 2), where we find that girls have significantly smaller and slower developing thalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala than boys with or without normalizing for head size, however, no male-female difference was found in right or left hemisphere caudate nucleus. These results differ significantly from data collected in higher income settings, which do not show such a pronounced gender effect until later in childhood9. Investigating environmental factors associated with overall increased or decreased anatomical values (Tables 1 and 2), we find that being male and having higher WAZ are significantly associated with increased whole-brain and regional WM and GM volumes. Higher maternal education was significantly associated with whole-brain WM volume, as well as amygdala, and hippocampal GM volume. Increased HAZ was associated with increased hippocampal and left amygdala volume, and improved sanitation (access to a flush toilet) was associated with whole-brain gray matter volume.Discussion

Results here present the first findings of brain growth trends in LMIC children. While the impact of malnutrition (underweight), sanitation, and overall SES on brain development was expected, developmental differences between boys and girls was surprising. Within India, gender disparities in infant nutrition, healthcare seeking, and other metrics of child health have been well reported10. In UP, the girl-to-boy ratio of 0.9 is amongst the lowest in the world, and the proportion of female to male newborns receiving healthcare is approximately 1:2. These gender disparities persist across all facets of life, with nearly twice as many girls as boys between 7-14 years of age not attending school. Within our cohort, we note that mothers were more than twice as likely to be illiterate as fathers (odds ratio = 2.5; p = 0.003). These early health inequalities may underpin observed neurodevelopmental differences: reduced infant nutrition and breastfeeding may impact WAZ, which we find consistently impacts neurodevelopment. Emphasizing a potential generation effect, as shown throughout maternal education is significantly associated with regional brain volumes and structural organization and integrity. Thus, girls may be born into a disadvantaged generational cycle that promotes worsened neurodevelopmental outcomes and sets the stage to impact their future offspring.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition. UNICEF / WHO / World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. 2019 2. Murray LK, Jordans MJD. Rethinking the service delivery of psychological interventions in low and middle income countries. BMC Psychiatry. 2016; 16:234. 3. Murray-Kolb LW et al. The MAL-ED cohort study: methods and lessons learned when assessing early child development and caregiving mediators in infants and young children in 8 low and middle income countries. Clin. Infect. Disease. 2014; 59: S261-S272. 4. Banerjee A. Et al. Reaching the dream of optimal development for every child, everywhere: what do we know about ‘how to’?. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019; 104:S1-S2. 5. Woldehanna T et al. The effect of early childhood stunting on children’s cognitive achievements: evidence from young lives Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health. Dev. 2018. 6. Chang SM. Et al. Early childhood stunting and later behavior and school achievement. J. Child Psychol. And Psychiatry. 2002; 43: 775-783. 7. Avants BB et al. An open source multivariate framework for n-tissue segmentation with evaluation on public data. Neuroinformatics. 2011; 9:381-400. 8. Patenaude B. Et al. A bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. NeuroImage. 2011; 56:907-922. 9. Kumar V, et al. Community-driven impact of a newborn-focused behavioral intervention in maternal health in Shivgarh, India. Int. J. Gynecol Obstet. 2012; 117: 48-55.Figures

Figure 1. Relationships between rate of child growth (linear growth and weight gain) and brain development. We find that early weight gain, associated with infant nutrition is a better predictor of brain development than child linear growth.

Figure 2. (a) Individual, (b) mean male and female, and (c) mean head size corrected male and female growth curves for whole brain white and gray matter volume. Overall, we find that girls have significantly smaller brain volumes, even when head size is controlled for, and slower rates of development, than boys.

Figure 3. Mean head size corrected male and female growth curves for (a) thalamus, (b) hippocampus, (c) caudate nucleus, and (d) amygdala volumes. Except for the caudate, we find that girls have consistently smaller overall structural volumes and slower rates of development than boys.

Table 1. From a systematic investigation of different child health and socioeconomic factors, we found the primary predictors of brain volume included gender (male > female), weight-for-age, maternal education, and sanitation.

Table 2. From a systematic investigation of different child health and socioeconomic factors, we found the primary predictors of regional brain volumes included gender (male > female), weight and height-for-age and maternal education.