4743

Comparison of Respiratory Motion Artifacts in T1-Weighted Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging using End-expiration and End-inspiration Breath-Holds1Department of Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Dignity Health Medical Foundation, San Francisco, CA, United States

Synopsis

Respiratory motion artifact is a common pitfall in MRI of the liver and no standard of practice currently exists for breath-hold imaging techniques. This retrospective observational study compared image quality between end-inspiration and end-expiration breath-holding techniques. Precontrast T1-weighted 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo imaging of the liver obtained using the two techniques were compared in 50 consecutive subjects, along with postcontrast sequences in a subset of 47. Three radiologists performed blinded evaluations of respiratory motion in the sequences. Breath-holding technique at end-expiration was significantly better at reducing respiratory motion artifacts, yielding fewer images of nondiagnostic quality than end-inspiration breath-holding technique.

Introduction

Respiratory motion artifact is a common pitfall in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver.1 Currently, no standard of practice exists for breath-hold imaging techniques, which vary among institutions. End-inspiration breath-holding is preferred by many institutions, as it is commonly believed to be better tolerated by patients. However, involuntary diaphragmatic relaxation seen during end-inspiration may represent an important cause of respiratory motion artifact during breath-hold imaging.2,3 In this study, we compare diagnostic image quality between end-inspiration and end-expiration breath-holding techniques, which surprisingly has not previously been evaluated in the MRI literature.Methods

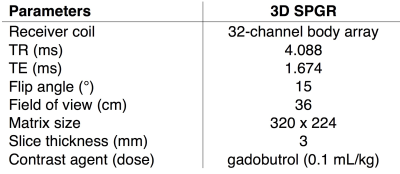

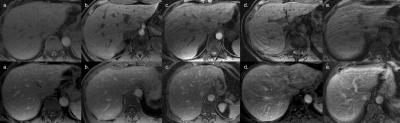

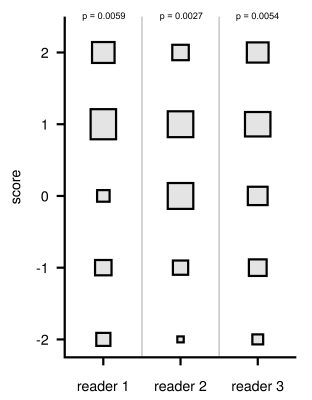

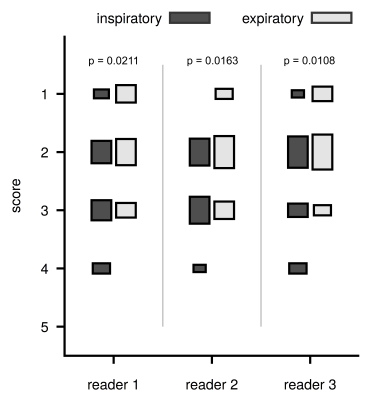

This retrospective observational study was approved by our institutional review board. The study took advantage of an institutional change in our liver protocol to acquire precontrast axial T1-weighted 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo (SPGR) images using both end-inspiration and end-expiration breath-holding techniques (Table 1). End-expiratory technique consisted of having the patient breathe out to a comfortable level, without forced expiration. Fifty consecutive subjects were identified for the study, including 25 women and 25 men, with a mean age of 58.9±14.2 years. All studies were performed on a 3.0T clinical MRI system. Mean acquisition time for each sequence was 13.44±2.45s. Breath-hold technique was verified by diaphragm position correlation on coronal images, with a higher diaphragm position confirming end-expiration technique. Of the exams performed, 25 cases were verified to be acquired using end-expiration breath-hold followed by end-inspiration breath-hold, and 25 cases were acquired with a reversed breath-hold order. Three radiologists performed blinded independent evaluations of each sequence using a 1 to 5 point scale, where 1 indicated no motion artifact and 5 indicated severe motion artifact rendering image quality nondiagnostic (Figure 1).4,5 Then, a blinded side-by-side assessment of each pair of sequences was performed using a -2 to 2 scale. A two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test combined with a Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to assess statistical significance, with a cutoff value set at α=0.05. A subgroup analysis using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was also performed comparing postcontrast venous phase axial T1-weighted 3D SPGR sequences, of which 26 were acquired at end-inspiration and 21 at end-expiration. Interreader agreement was calculated using an intraclass correlation coefficient.Results

For each of the three readers, there was a significant improvement (p≤0.0160) in motion scores for sequences acquired in end-expiration (pooled mean 2.65±0.91) over those acquired in end-inspiration (pooled mean 3.20±0.97). For end-expiration sequences, 45% received scores of 1 or 2, compared to 23% for end-inspiration. Similarly, 15% of end-expiration sequences received scores of 4 or 5, compared to 36% for end-inspiration (Figure 2). Side-by-side assessment of paired sequences favored end-expiration in 59% of cases, and found no difference between both breath-holding techniques in 21%, p≤0.0059. End-inspiration sequences were favored in only 20% of cases (Figure 3). No significant difference in motion scores was found when comparing the 25 cases acquired using end-expiration breath-hold first with the 25 cases acquired using end-expiration second (p≥0.0873). As seen in Figure 4, a subgroup analysis of postcontrast sequences also showed significantly better (p≤0.0211) mean motion scores when end-expiration breath-hold (pooled mean 1.98±0.68) was used compared to end inspiration (pooled mean 2.54±0.79). The intraclass correlation coefficient ranged from 0.516 to 0.706, indicating fair and good agreement for all scores between the three readers.Discussion

In our study, end-expiratory breath-holding technique was significantly better at reducing respiratory motion artifacts than end-inspiratory breath-holding technique for precontrast and postcontrast axial T1-weighted 3D SPGR MRI of the liver. Acquisition using end-expiratory breath-hold technique also yielded more images with minimal or no motion artifact and less nondiagnostic images. These findings may be explained by involuntary relaxation of the inspiratory muscles during end-inspiration breath-hold, which causes an upward diaphragmatic movement that can lead to motion artifact.2,3 During end-expiration breath-hold, these muscles are already relaxed and diaphragmatic displacement is therefore less significant.2,3 Furthermore, end-expiration represents the longest motionless phase in the respiratory cycle.6 No significant difference in motion scores was found when the order of breath-hold acquisition was taken into account. This suggests that repeated breath-holds and imaging were not confounding factors. Potential limitations of our study included small number and lack of paired comparisons for the postcontrast cases, although significant improvements in motion scores were still observed albeit with greater p-values.Conclusion

Breath-hold imaging techniques vary among institutions. This study found a significant decrease in respiratory motion artifact when end-expiration breath-hold is used compared to end-inspiration on both precontrast and postcontrast T1-weighted liver MRI. Further research can evaluate if this technique allows for improved slice registration and subtraction image creation.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Maniam S, and Szklaruk J. Magnetic resonance imaging: Review of imaging techniques and overview of liver imaging. World J Radiol. 2010;2(8):309–322.

- Holland AE, Goldfarb JW, et al. Diaphragmatic and cardiac motion during suspended breathing: preliminary experience and implications for breath-hold MR imaging. Radiology. 1998;209(2):483-9.

- Plathow C, Ley S, et al. Assessment of reproducibility and stability of different breath-hold maneuvres by dynamic MRI: comparison between healthy adults and patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Radiol. 2006 Jan;16(1):173-9.

- Davenport MS, Viglianti BL, et al. Comparison of acute transient dyspnea after intravenous administration of gadoxetate disodium and gadobenate dimeglumine: effect on arterial phase image quality. Radiology. 2013;266(2):452-61.

- Pietryga JA, Burke LM, et al. Respiratory motion artifact affecting hepatic arterial phase imaging with gadoxetate disodium: examination recovery with a multiple arterial phase acquisition. Radiology. 2014;271(2):426-34.

- Ritchie CJ, Hsieh J, et al. Predictive respiratory gating: a new method to reduce motion artifacts on CT scans. Radiology. 1994;190(3):847-52.

Figures