4702

Imaging beta-cell function in the mouse pancreas with an implanted imaging window by MRI1University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States, 2The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel, 3University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, United States

Synopsis

We have successfully implanted an imaging window onto the mouse abdomen to locate and hold the tail of the pancreas in place. By use of this MR-compatible window we were able to show with MRI and a Gd-based zinc sensor the non-uniform regional secretion of zinc and insulin as a response to glucose in the tail of the mouse pancreas. This surgical technique and imaging technology could be used to successfully monitor beta-cell function longitudinally through the development of the various diseases of the endocrine pancreas with MRI.

Purpose

Previous studies from our lab have focused on detecting glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) from the pancreas using a variety of Gd-based zinc-responsive MR contrast agents1,2. However, locating and imaging the rodent pancreas in vivo with any non-invasive imaging technique is challenging. Longitudinal GSIS imaging studies of the rodent pancreas are difficult in part due to the uncertainty of consistently locating the same piece of tissue over multiple imaging sessions. Thus, here we explore using a surgical method to isolate and hold the tail of the pancreas in place by implantation of an imaging window on the mouse abdomen and perform beta-cell function imaging in vivo by MRI using a Gd-based zinc sensor.Methods

Gd-based zinc sensor: GdDO3A was linked to a lower affinity Zn2+-binding moiety (KD(Zn) = 2.35µM) to yield a new complex, described elsewhere as GdL2.3.

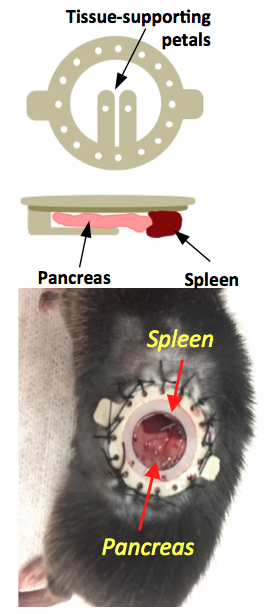

Pancreatic window implantation: A previously developed implantable imaging window4 was implanted in the abdomen of male C57Bl6 mice. Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine (100/16 mg/kg) cocktail and kept at 37°C throughout surgery. The left side of the mouse abdomen was shaved, a circular incision on the skin was made, and the imaging window was sutured to the skin. To expose the tail of the pancreas, a smaller incision on the muscle/ peritoneum was made below the window. The pancreas was carefully retracted and attached with tissue adhesive to the supporting petals on the window (Fig.1). Glycerol drops were placed on the surrounding tissue to avoid large air voids. A circular glass coverslip was placed on the window and sealed in place with a c-ring.

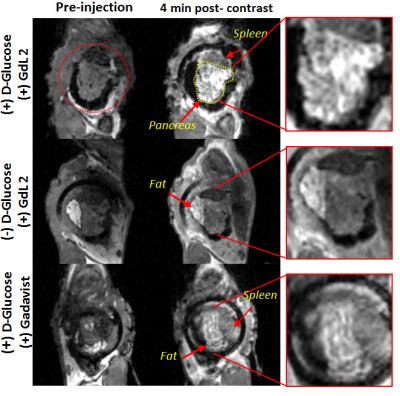

In vivo MRI: Window-implanted mice were imaged with a 4.7 T Varian scanner and anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. Two ge3d T1-weighted scans were performed to obtain a pre-injection baseline (TE/TR=1.69/3.5 ms, Average = 4, θ = 20°). Animals received either 0.07 mmol/kg GdL2 (i.v.) plus 2.2 mmol/kg glucose or saline (i.p.), or 0.07 mmol/kg Gadavist (i.v.) plus 2.2 mmol/kg glucose. Sequential 3D T1-weighted scans were obtained for a total of 48 minutes. Images were analyzed using ImageJ, and the change in MR signal intensity was reported as a percentage compared to pre-injection scans.

Results and Discussion

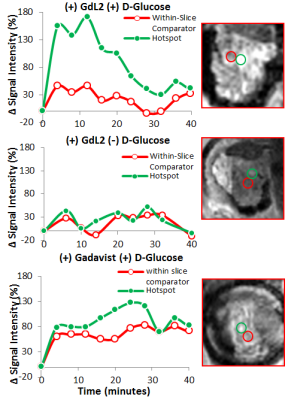

It is known that upon a glucose challenge, zinc and insulin are co-secreted into the extracellular space and this biological function can be directly imaged my MRI.5 However, in vivo MRI of the rodent pancreas has been a challenging task as the pancreas is not a solid organ but rather a thin piece of tissue intertwined with other abdominal organs. All imaging experiments required secondary ex-vivo confirmation of the “localized” pancreas and thus limited our ability to perform longitudinal studies of beta-cell function. Recently, we adopted a previously reported surgical procedure4 to implant an imaging window in the mouse abdomen with the goal of exposing and holding the tail of the pancreas in place (Fig.1). MR images after injection of GdL2 plus glucose revealed non-uniform, hyper-intense regions in the tail of the pancreas (Fig. 2). We hereafter refer to these hyperintense regions as “hotspots”. Control mice given saline instead of glucose or Gadavist instead of GdL2 (Fig.2) did not show hotspots. This suggests that these regions of intense enhancement reflect insulin/zinc secretion (Fig.2). Quantified imaging intensities normalized to muscle and compared to the pre-injection baseline scans are shown in Fig.3. ROIs identifying the hotspots (green) and comparator ROIs in the same slice (red) were compared; the relative hotspot enhancement in the tail of the pancreas was most prominent after injection of GdL2 plus glucose to stimulate insulin secretion. The pancreas of mice after injection of Gadavist as a control showed weak hotspots in some regions indicating that paramagnetic agents such as these do not distribute uniformly throughout the tissue. However, a comparison of signal enhancement over time after injection of Gadavist showed that those regions that appear to be enhanced were not significantly higher in comparison to other ROIs within the same slice. The kinetics of insulin secretion has been thoroughly elucidated in vitro but vast differences have been reported in vivo.6 The existence of subpopulations of beta-cells that differ in their sensitivity to respond to insulin secretagogues have been reported in the tail and head of the pancreas, referred to as “first responder islets”.7Conclusions

Here, we report MR imaging results that parallel the characteristics of “first responder” islets in the tail of the mouse pancreas. This implanted imaging window methodology should allow longitudinal studies of beta-cell response in vivo during progression of type 2 diabetes and as beta-cells respond to therapy.Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (P41- EB015908, R01-DK095416) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (AT-584) is gratefully acknowledged.References

1 Yu, J. et al. Amplifying the sensitivity of zinc(II) responsive MRI contrast agents by altering water exchange rates. J Am Chem Soc 137, 14173-14179, doi:10.1021/jacs.5b09158 (2015).

2 Esqueda, A. C. et al. A new gadolinium-based MRI zinc sensor. J Am Chem Soc 131, 11387-11391, doi:10.1021/ja901875v (2009).

3 Martins, A. F. et al. Second generation MRI sensors with lower affinity for zinc ions improve detection of insulin secretion from the mouse pancreas in vivo. J Am Chem Soc Submitted (2017).

4 Bochner, F., Fellus-Alyagor, L., Kalchenko, V., Shinar, S. & Neeman, M. A Novel Intravital Imaging Window for Longitudinal Microscopy of the Mouse Ovary. Sci Rep 5, 12446, doi:10.1038/srep12446 (2015).

5 Kelleher, S. L., McCormick, N. H., Velasquez, V. & Lopez, V. Zinc in specialized secretory tissues: roles in the pancreas, prostate, and mammary gland. Adv Nutr 2, 101-111, doi:10.3945/an.110.000232 (2011).

6 Zhu, S. et al. Monitoring C-Peptide Storage and Secretion in Islet beta-Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Diabetes 65, 699-709, doi:10.2337/db15-1264 (2016).

7 Stefan, Y., Meda, P., Neufeld, M. & Orci, L. Stimulation of insulin secretion reveals heterogeneity of pancreatic B cells in vivo. J Clin Invest 80, 175-183, doi:10.1172/JCI113045 (1987).

Figures