3762

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy prior to natural menopause is associated with Alzheimer’s disease-like reductions in gray and white matter1CMIV, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 2Womens' Clinic, University Hospital Linköping, Linköping, Sweden, 3Dept. of Acute Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 4Unit of Gender Studies, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 5University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Dept. of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Synopsis

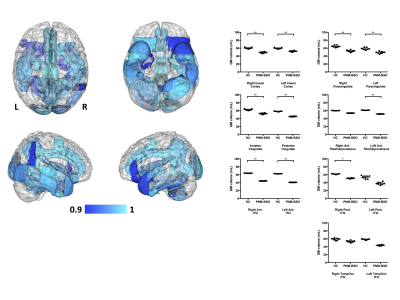

Women with Breast Cancer Gene mutations (BRCAm) are recommended to undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy prior to natural menopause (PNM-BSO) in order to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. This surgery is associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease (AD). In comparison with healthy women, BRCAm women who had undergone PNM-BSO exhibited decreased gray matter volume across frontal and medial-temporal regions, as measured using the quantitative QRAPMASTER sequence. These regions included many previously linked with AD including, parahippocampal gyrus, cingulate cortex, and inferior temporal gyrus. White matter reductions were only observed in a limited number of superior longitudinal tracts.

Introduction

Women with Breast Cancer Gene mutations (BRCAm) are recommended to undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy prior to natural menopause (PNM-BSO) in order to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. While PNM-BSO reduces the development of breast cancer by 50%1-2 and ovarian, fallopian, and peritoneal cancers by 80%3 in women with BRCAm, epidemiological studies have also shown PNM-BSO correlates with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD)4-6. This increased risk of AD post-PNM-BSO is thought to stem from the sudden loss of endogenous estradiol (E2)7, however, no data exist to elucidate the underlying morphological brain changes that may occur post-PNM-BSO and whether such changes to gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) volumes are similar to those observed in preclinical and early AD. If undergoing PNM-BSO constitutes an increased risk for development of AD, we hypothesized that these women would exhibit reduced GM volume compared with healthy, age-matched women, particularly in medial fronto-temporal regions previously linked to AD8, including parahippocampus, hippocampus, insula, and temporal lobes.Methods

Nine healthy, premenopausal women (age=40.7±6.5 yrs) and eight BRCAm women who had undergone PNM-BSO (age=47.8±5.7 yrs) were scanned using the QRAPMASTER quantitative MRI sequence9 on a Philips 3T Ingenia scanner. The PNM-BSO women were otherwise healthy and examined 7±3 yrs post-surgery. Synthetic T1-weighted (T1W) images and whole brain, quantitative maps of GM and WM were generated using SyMRI 8 software (SyntheticMR AB, Linköping, Sweden). Each participant’s synthetic T1W image was normalized to MNI space, and these normalization parameters were inverted to warp both the Harvard-Oxford cortical and subcortical parcellated and the JHU labeled parcellated atlases to each subject’s space. All image-based analyses were performed using FLIRT and FNIRT in FSL. The mean values for each participant for each parcellation in the GM and WM atlases were extracted. Between-group t-tests were performed on the total brain parenchymal volumes (BPV) of GM and WM, and all atlas-based GM regions and WM tracts. Multivariate tests, controlling for age at the time of scan, were also performed on select GM regions previously linked to morphologic changes in AD. Finally, for the PNM-BSO group only, partial correlations, controlling for age, were performed to investigate the relationship between GM and WM and time since PNM-BSO. Given the preliminary nature of these data, any statistical evidence at p<0.1, uncorrected for multiple comparisons, was considered to be of interest.Results

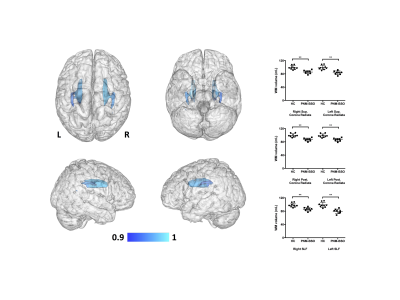

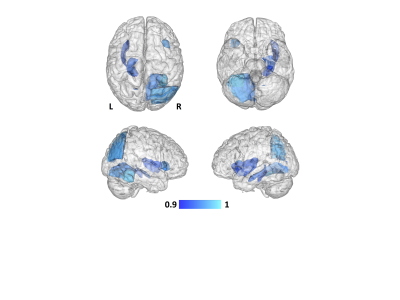

No between-group differences were noted for the total BPV of GM or WM (p>0.6). Despite this lack in whole-brain GM volume difference, GM reductions were observed for the PNM-BSO group across a number of the GM parcellations (Fig 1), covering large portions of the cortex, subcortex, and cerebellum. Of particular relevance to the potential development of AD, the multivariate tests (controlling for age) indicated specific GM reductions in bilateral insula (F(2,13)=3.5, p<0.06), cingulate cortex (F(4,11)=2.9, p<0.07), anterior parahippocampal gyri (F(2,13)=3.7, p<0.05), and inferior temporal gyrus (F(6,9)=4.7, p<0.02). Within WM, PNM-BSO related volume reductions were observed in bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and superior and posterior corona radiata (CR) (Fig 2). These results for WM were confirmed using multivariate tests controlling for age: SLF (F(2,13)=4.9, p<0.03) and CR (F(4,11)=4.7, p<0.019). Finally, when considering the effect of time since PNM-BSO, we found that time since surgery correlated with reduced GM in a number of temporal-occipital regions, including left parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, and insula (Fig 3). No relationship was observed for WM.Discussion

We observed that BRCAm women who underwent PNM-BSO exhibited GM reductions in large portions of the medial frontal and temporal cortices, providing the first quantitative evidence that PNM-BSO is associated with a similar pattern of regional GM reductions across the whole brain as seen in AD. Additionally, GM reductions in several medial temporal and frontal regions correlated with time since PNM-BSO, suggesting that GM volume loss does not occur immediately after surgical menopause and loss of endogenous E2. We further observed that WM changes were localized to a limited number of superior longitudinal tracts, suggesting an initial vulnerability only in GM in these women. We note that two BRCAm women reported past or current use of hormone replacement therapy, however, outlier analysis determined that these two women were not driving our findings. These results extend our previously reported preliminary observations that PNM-BSO is associated with reduced hippocampal volume and medial temporal lobe cortical thickness10-11.Conclusions

These preliminary data add significant first evidence that PNM-BSO is associated with morphological changes across the whole brain similar to those observed in preclinical and early AD.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Eisen et al., Breast cancer risk following bilateral oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: an international case-control study. 2005 J Clinical Oncology 23, 7491-7496.

2. Rebbeck et al., Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. 2002 New England J Medicine 346, 1616-1622.

3. Finch et al., Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tub, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. 2006 JAMA 296, 185-192.

4. Rocca et al., Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. 2007 Neurology 69, 1074-1083.

5. Phung et al., Hysterectomy, oophorectomy and risk of dementia: A nationwide historical cohort study. 2010 Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 30, 43-50.

6. Bove et al., Age at surgical menopause influences cognitive decline and Alzheimer pathology in older women. 2014 Neurology 82, 222-229.

7. Sherwin, Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women. 2003 Endocrine Reviews 24, 133-151.

8. Mak et al., Structural neuroimaging in preclinical dementia: From microstructural deficits and grey matter atrophy to macroscale connectomic changes. 2017 Ageing Research Reviews 35, 250-264.

9. Warnjes et al., Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: optimization for clinical usage. 2008 MRI 60, 320-329.

10. Duchesne et al., Hippocampal integrity in Swedish women with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy prior to natural menopause: preliminary findings. 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, London, England, July 16-20.

11. Gervais N et al., Predictors of cognitive function in women following oophorectomy: implications for AD risk. 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, London, England, July 16-20.

Figures