2340

Resting-state fMRI reveals altered auditory and pain perception networks in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)1Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2Department of Medicine, Snyder Institute for Chronic Diseases, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 3Radiology, Clinical Neurosciences, Psychiatry, The Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Synopsis

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic and painful inflammatory-mediated disease of the gastrointestinal system. Recent animal model evidence suggests that cognitive deficits and mood changes experienced by IBD patients are not merely emotional reactions, but result from structural and functional changes in the brain. We used dual-regression analysis of resting-state fMRI data to identify alterations in functional connectivity in IBD patients compared to controls. Connectivity was altered with auditory and pain perception networks, which may help explain behavioural symptoms (hearing loss, pain) commonly experienced by IBD patients.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a painful and chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal system. IBD patients also experience fatigue, mood disorders and cognitive deficits.1 Animal models of IBD have demonstrated brain structural and functional changes, which are not necessarily correlated with indicators of disease severity.2 In this study, we used dual regression analysis of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data3 to determine if functional networks associated with symptoms commonly experienced by IBD patients are altered relative to healthy controls.Methods

Sixteen newly-diagnosed IBD patients and 16 age- and gender-matched healthy controls participated in the study. Resting-state fMRI and T1-weighted images were collected using a 3 Tesla MR scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). All images were processed and analyzed using FSL software.4 Preprocessing steps included brain extraction, slice timing correction, MCFLIRT motion correction, spatial smoothing (6-mm) and low-pass temporal filtering. Preprocessed images were registered to T1-weighted images and then to the MNI152 standard space brain template. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was used in MELODIC to identify and regress out time-varying fMRI signals caused by artifact.4 Dual regression analysis of functional networks was used to identify voxel-wise differences between IBD patients and healthy controls. We investigated 21 atlas-based functional networks.5 For each of these networks, the average time-varying fMRI signal was determined and used in a General Linear Model (GLM) analysis to derive brain spatial maps associated with that network, for each participant. To identify brain regions that significantly differed between IBD patients and controls in terms of connectivity with that specific functional network, a between-group GLM analysis was performed. Maps of differential connectivity (i.e., IBD > controls and IBD < controls) were generated using a statistical threshold at a corrected p value of 0.05, using randomize (a nonparametric permutation-based tool of FSL).Results and Discussion

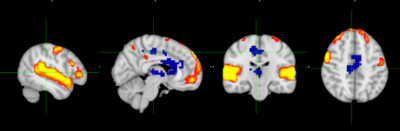

Functional connectivity was altered in IBD patients relative to the controls in a number of functional networks, including the transverse temporal gyri network (Figure 1). Decreased connectivity in IBD patients was observed between the transverse temporal gyri (also called Heschl’s gyri) and the pons as well as the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus, the caudate head and the supplementary motor area. Transverse temporal gyri include the primary auditory cortices (A1; BA 41/42), which are associated with auditory processing such as tone and pitch discrimination, speech and music.6 The medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus is considered as a relay for ascending auditory information to the cortex.7 Studies have showed that sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and inner ear dysfunction are more prevalent in IBDs compared to the normal subjects, suggesting an association between SNHL and immune-mediated diseases.8,9 Decreased functional connectivity within this network may help explain the hearing loss commonly observed in IBD patients.

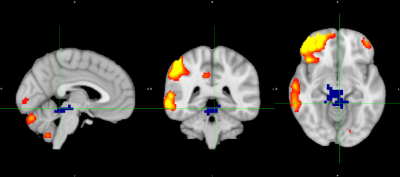

Functional connectivity alterations were also observed in the right lateralized fronto-parietal network (Figure 2). Increased functional connectivity in IBD patients was observed with the pons and periaqueductal gray matter (PAG). Right lateralized fronto-parietal regions include right BA 44/45 and 22/39/40. This network is reported to be involved in cognition, and also specifically for perception, somesthesis and pain.5 Given that the PAG is associated with ascending pain transmission and anxiety, increased connectivity with this network may help explain IBD patients’ sense of pain in addition to anxiety. Future correlation analyses with cognitive and clinical scores are planned to explore more fully the association between symptoms and these functional alterations.

Conclusion

IBD is associated with altered functional connections in regions associated with auditory processing and perception of pain. Dual regression analysis of resting-state fMRI data is an effective tool to determine significant alterations in brain functional connections associated with IBD. Further study is required if we are to better understand brain mechanisms underlying IBD-related symptoms, with the ultimate goal of developing behavior-targeted therapies to improve the quality of life of IBD patients.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a CIHR Team grant (BG,GK,MS) and an NSERC I3T Studentship (FH).References

1. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46-54

2. Bercik P, Collins SM, Verdu EF. Microbes and the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(5):405-413.

3. Beckmann CF, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Smith SM. Group comparison of resting-state FMRI data using multi-subject ICA and dual regression. 2009;181.

4. Jenkinson M. FSL. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782-790.

5. Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, et al. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(31):13040-13045.

6. Angela R. Laird, P. Mickle Fox, Simon B. Eickhoff, et al. Behavioral interpretations of intrinsic connectivity networks. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23(12):4022-4037.

7. Purves D, Augustine G, Fitzpatrick D. The Auditory Thalamus. 2nd ed. Neuroscience; 2001.

8. Karmody CS, Valdez TA, Desai U, Blevins NH. Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30(3):166-170.

9. Wengrower D, Koslowsky B, Peleg U, et al. Hearing loss in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(7):2027-2032.

Figures