2068

Nonlinear pattern of the emergence of white matter hyperintensity in healthy Han Chinese: an adult lifespan study1Aging and Health Research Center, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2Division of Interdiscplinary Medicine and Biotechnology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Brain Research Center, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan, 4Department of Psychiatry, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, 5Insitute of Neuroscience, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

Synopsis

WMH is one of the most obvious imaging traits in the aged brain. There is evidence that the WMH volume may have the potential to track with age and age-related cognitive decline. However, no study has investigated the trajectory of WMH progression and their impact on cognition during normal aging process. We show that increased age is nonlinearly correlated with increased PVWMH. In two-mediators mediation model, PVWMH is found to mediate the age-related decline of MMSE, but not DWMH. This study suggested that PVWMH could be a potential, and feasible biomarker in predicting age-related cognitive decline across the adult lifespan.

INTRODUCTION

White matter

hyperintensities (WMH) are prevalent in the elderly and are often accompanied by

cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia, which

is one of the most obvious imaging traits in the aged

brain.

There is evidence

that the WMH volume may have the potential to track with chronological age and

age-related cognitive decline. However, although previous studies

have noted different etiologies and pathophysiologies in WMH in the periventricular

and deep white matter regions, its role in the aging process remains

controversial.

Therefore, it is essential to investigate the roles of

WMH in different locations of the brain and its relationship to the decline of cognitive-related

function in healthy aging.

In

this study, two types of WMH were examined using a large cohort of healthy

subjects ranging in age from early to late adulthood. From the perspective of

revealing the pivotal roles of regional WMH in the aging process, we aimed to determine:

1) the change in the trajectory of PVWMH and DWMH across the adult lifespan; and

2) if PVWMH or DWMH differentially mediate the aging effect on the variability

of cognitive function.

METHODS

The current study included 312 healthy individuals aged 21 to 89 years who received structural magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive assessments. To automatically identify different WMH in the brain, we used the lesion segmentation toolbox (LST) 1, which was implemented in Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM8). WMH volume in the periventricular (PVWMH) and deep white matter (DWMH) regions were computed and fitted using different regression models to evaluate the trajectory of WMH changes across the lifespan. We examined the best fit of log-transformed WMH by functions of age according to the parameters of SSE, R2, the variance of SSR, and AIC acquired using 10-fold cross-validation. To comprehensively examine whether age-related changes in cognition are mediated by age-related changes in regional WMH, a mediational model with multiple mediators (PVWMH and DWMH) was constructed using the PROCESS macro with the principles described by Baron and Kenny (1986) . 2-3

RESULTS

Eighteen participants were excluded because of segmentation failure and extensive motion during MRI scanning. The 312 participants ranged in age from 21 to 89 years (mean age, 50.7 ± 20.4 years), and 158 were male.

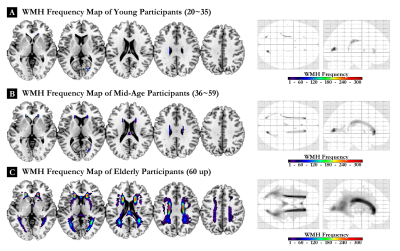

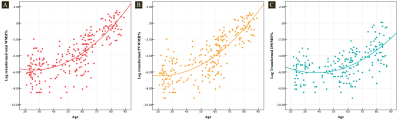

Group differences in

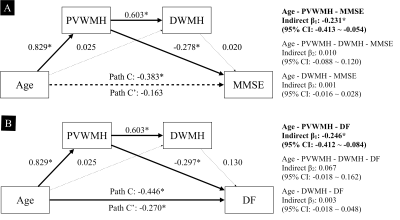

normalized WMH volumes were compared and are presented in Figures 1 (representative frequency maps). The quadratic model was shown to be the best for characterizing the relationship between WMH changes and chronological age. Plots of the quadratic curve regressions are presented in Figure 2. As seen in Figure 2, there was a considerable increase in total WMH volume and PVWMH in the 50-60 year age group, whereas DWMH increased marginally between 21 and 89 years of age. We further utilized mediation analysis to examine the role of regional WMH in the normal aging process. With two-mediator mediation model, PVWMH is found to mediate the age-related decline of MMSE fully, but not DWMH (Figure 3).DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that WMH volume has a steeper increase in the fifth decade of life and no difference in WMH volume between young and middle aged individuals. This finding is also consistent with a recent study that supported a similar trajectory of WMH progression using large adult (40-65 years) dataset.4 One possible explanation for this finding is that cardiovascular issues, which are the leading risk factors for WMH development, start to increase dramatically after the age of 54 years.5 It has also been found that hypertension is a risk factor for the development of WM lesions that already exist in middle aged individuals .6 In this study, with a dataset spanning adulthood, we further suggested a possible causal pathway, namely that PVWMH acts as a critical mediator of the decline of some specific aging-related cognitive abilities, especially attention and short-term memory. The results from a longitudinal study by van den Heuvel et al. 7 support our findings that the progression of PVWMH, but not DWMH, positively correlates with the decline in mental processing speed. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, to our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate a nonlinear relationship between age and brain WMH using lifespan data, and suggest a steeper increase in the progression of WMH between the ages of 50 to 60 years. Moreover, cognitive decline with age is, in part, mediated by age-related increases in WMH, especially PVWMH. Our findings not only provide a better understanding of WMH progression across adult lifespan, but also support different cognitive correlates for PVWMH and DWMH that may be potential early biomarkers of cognitive aging.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan (MOST 103-2314-B-075-067-MY3; MOST 104-2218-E-010-007-MY3; MOST 104-2633-B-400-001; MOST 104-2314-B-075 -078 -MY2); Taiwan Veterans General Hospital (VGHUST102-G1-2-1, and VGHUST103-G1-4-1); Brain Research Center, National Yang-Ming University, Taiwan; and the Ministry of Education, Aim for the Top University Plan, Taiwan. The authors also acknowledge the MRI support received from the MRI Core Laboratory of National Yang-Ming University, Taiwan.References

- Schmidt P, Gaser C, Arsic M, Buck D, Forschler A, Berthele A, Hoshi M, Ilg R, Schmid VJ, Zimmer C, Hemmer B, Muhlau M (2012) An automated tool for detection of FLAIR-hyperintense white-matter lesions in Multiple Sclerosis. Neuroimage 59:3774-3783.

- Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis : a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173-1182.

- Habes M, Erus G, Toledo JB, Zhang T, Bryan N, Launer LJ, Rosseel Y, Janowitz D, Doshi J, Van der Auwera S, von Sarnowski B, Hegenscheid K, Hosten N, Homuth G, Volzke H, Schminke U, Hoffmann W, Grabe HJ, Davatzikos C (2016) White matter hyperintensities and imaging patterns of brain ageing in the general population. Brain 139:1164-1179.

- Ramos R, Marrugat J, Basagana X, Sala J, Masia R, Elosua R, Investigators R (2004) The role of age in cardiovascular risk factor clustering in non-diabetic population free of coronary heart disease. Eur J Epidemiol 19:299-304.

- de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC, Hofman A, van Gijn J, Breteler MM (2002) Hypertension and cerebral white matter lesions in a prospective cohort study. Brain 125:765-772.

- van den Heuvel DM, ten Dam VH, de Craen AJ, Admiraal-Behloul F, Olofsen H, Bollen EL, Jolles J, Murray HM, Blauw GJ, Westendorp RG, van Buchem MA (2006) Increase in periventricular white matter hyperintensities parallels decline in mental processing speed in a non-demented elderly population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77:149-153.

Figures

Figure 1. Frequency map of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in different age groups across the adult lifespan.

This figure shows representative WMH frequency maps from participants in the (A) young adult, (B) middle age, and (C) elderly groups. Color bars denote the frequency of WMH prevalence.

Figure 2. The relationship between age and log-transformed white matter hyperintensities (WMH).Each dot indicates the percentage of WMH (log-transformed) in the whole brain of each participant (subjects with 0% WMH in the brain were removed). Each line reveals a considerable quadratic increase pattern of WMH, and the degree is higher in the (A) whole brain (red) and in the (B) periventricular region (orange), whereas (C) WMH in the deep WM region (blue) increased marginally with age. PVWMH, periventricular WMH; DWMH, deep WMH.