0353

Impact of Routine Magnetic Resonance Imaging on Diagnosis and Treatment of Women with Benign Gynecologic Conditions Seen in a Multidisciplinary Fibroid Center1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Obstetrics & Gynecology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Pelvic ultrasounds often represent the first and only line of imaging for uterine fibroid evaluation. Our study aims to determine the added value of routine pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on diagnosis and treatment of women presenting with symptomatic uterine fibroids. A retrospective review was performed on 569 consecutive women referred to our multidisciplinary fibroid center over a three-year period. Compared to ultrasound alone, MRI affected diagnosis in over a third of patients, which also altered treatment options. These findings justify the use of routine pelvic MRI in women with symptomatic fibroids, particularly those presenting with dysmenorrhea.

Introduction

Uterine fibroids are the most common solid tumor of the female pelvis, affecting 80% of women over the age of 50 and causing symptoms in up to 30%.1,2 Pelvic ultrasounds often represent the first and only line of imaging for fibroid evaluation. However, concurrent gynecologic conditions such as adenomyosis and endometriosis may contribute to the patient’s symptomatology. These conditions often alter treatment options and are more difficult to detect on ultrasound.3-6 The purpose of this study is to determine the impact of routine pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation on diagnosis and treatment of women presenting with symptomatic uterine fibroids.Methods

This retrospective observational study was approved by our institutional review board. Our study included 569 consecutive women with a presumed diagnosis of fibroids referred to our multidisciplinary fibroid center from April 2013 to July 2017. All patients underwent pelvic MRI prior to being counseled by a team comprised of a gynecologist, interventional radiologist, and body MRI radiologist. Treatment options depended on clinical and imaging findings and included expectant management, medical treatment, surgery, uterine artery embolization (UAE), and MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS). One hundred twenty-seven patients with no prior pelvic ultrasound imaging or report available and 99 patients with an interval between ultrasound and MRI exams greater than a year were excluded from this study. Main presenting symptoms, ultrasound findings, MRI findings, and choice of treatment were recorded for all patients. Subgroup analyses were performed comparing patients with a final diagnosis of fibroids alone and patients for whom MRI provided additional diagnoses. Chi-squared test was used to evaluate for statistical significance between the subgroups, with a p value ≤ 0.05 considered to be significant.Results

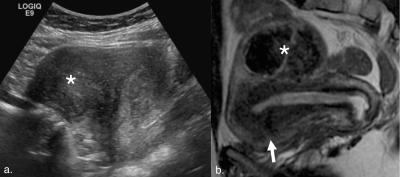

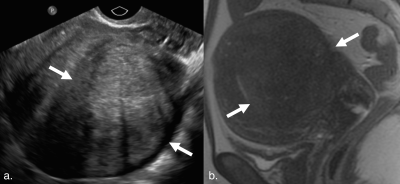

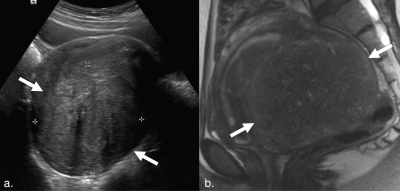

Our final cohort included 343 women with a mean age of 44.0±6.8 years. Average time between ultrasound and MRI studies was 89.2±103.3 days. Pelvic MRI modified ultrasound diagnosis in 127 patients (37.0%) (Figure 1). The most common additional diagnoses found on MRI were adenomyosis in 94 patients (27.4%), endometriosis in 45 patients (13.1%), and endometrial polyps in 5 patients (1.5%). Nine patients (2.6%) diagnosed with fibroids on ultrasound were found to have focal adenomyosis without fibroids on MRI (Figures 2 and 3).

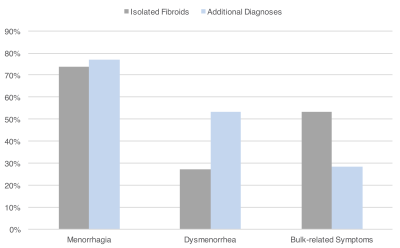

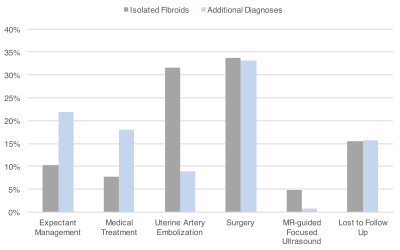

When comparing patients with a final diagnosis of fibroids alone and patients for whom MRI provided additional diagnoses, no significant age difference was found between both groups (mean age of 43.9±6.3 versus 44.2±7.7 years, p = 0.6694). In comparison to patients with isolated fibroids, those with additional MRI diagnoses presented with dysmenorrhea significantly more frequently (27.3% versus 53.5%, p < 0.0001) and with bulk-related symptoms significantly less frequently (53.2% versus 28.3%, p < 0.0001) (Figure 4). Both groups presented with menorrhagia at a similar rate (73.7% versus 77.2%, p = 0.4875). Submucosal fibroids were significantly more common in women with isolated fibroids than those with additional MRI diagnoses (55.6% versus 36.7%, p = 0.0036). When compared with patients with fibroids only, patients with additional MRI diagnoses were significantly less likely to be treated with UAE (31.7% versus 9.4%, p < 0.0001) and MRgFUS (4.9% versus 0.8%, p = 0.0434), and significantly more likely to be managed medically (18.1% versus 7.8%, p = 0.0047) (Figure 5).

Discussion

Compared to pelvic ultrasound alone, our study found that pelvic MRI affected diagnosis in over a third of women presenting with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Adenomyosis, endometriosis, and endometrial polyps were the most common additional MRI findings. These patients presented with significantly more dysmenorrhea, whereas patients with isolated symptomatic fibroids presented with significantly more bulk-related symptoms. Menorrhagia was a common complaint in both groups with submucosal fibroids being the most common cause in patient with fibroids alone and adenomyosis as the main explanation in patients with additional diagnoses. These additional diagnoses affected counseling and management with medical management being preferred significantly more frequently and UAE and MRgFUS being chosen significantly less frequently. These findings demonstrate that in patients with a presumed diagnosis of symptomatic fibroids, the use of routine pelvic MRI leads to more accurate diagnosis and more appropriate treatment. In places where MRI is not widely available, further MRI evaluation would likely be most beneficial in women presenting with dysmenorrhea. The main limitation of our study is the lack of histopathologic correlation as reference standard, as many patients with adenomyosis and endometriosis chose medical management.Conclusion

The use of pelvic MRI, in addition to ultrasound, affects diagnosis and management in a substantial number of women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Implementation of routine pelvic MRI may be particularly justified in a subgroup of women presenting with dysmenorrhea.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100-107.

- Buttram VC Jr, Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril. 1981;36(4):433–45.

- Battista C, Capriglione S, et al. The challenge of preoperative identification of uterine myomas: Is ultrasound trustworthy? A prospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;193:1235-1241.

- Friedman H, Vogelzang RL, Mendelson EB, et al. Endometriosis detection by US with laparoscopic correlation. Radiology. 1985;157(1):217-20.

- Pelage JP, Jacob D, et al. Midterm results of uterine artery embolization for symptomatic adenomyosis: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234(3):948-53.

- Bratby MJ, Walker WJ. Uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic adenomyosis-mid-term results. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70(1):128-32.

Figures