4988

MR versus CT Imaging for Identifying the Etiology of Abdominal Pain in Emergency Department Patients1Emergency Medicine, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Radiology, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Radiology, St. Mary's Hospital, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Our study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of MR versus CT for identifying the etiology of abdominal pain in emergency department patients. This is a prospective study that included patients ≥12-years-old who were being evaluated for possible appendicitis. All patients underwent both MR and CT; images were interpreted by three radiologists who were blind to the patient’s outcome. There were 113 instances of acute abdominal processes (15 different diagnoses). The overall accuracy of NC-MR, CE-MR, and CT was 77%, 83%, and 90% for individual reads and 82%, 84%, and 94% for consensus reads.

Introduction

Nearly one-third of all non-injury related emergency department (ED) visits are due to patients experiencing abdominal pain.1 A common concern among these patients is appendicitis, which affects over 250,000 people annually in the United States.2 However, of those who undergo computed tomography (CT) for possible appendicitis, only 23% of them have appendicitis while another 30% have an alternate diagnosis.3 To avoid exposure to ionizing radiation and iodinated contrast, MR has been studied as an alternative to CT when evaluating such patients. However, the accuracy of MR to identify one of a number of potential causes of abdominal pain has not been systematically studied.Purpose

To determine and compare the diagnostic accuracy of MR versus CT for identifying acute abdominal pathology in ED patients presenting with abdominal pain.Methods

This is a HIPAA-compliant and IRB-approved prospective study of a convenience sample of patients presenting with abdominal pain to the ED of an academic medical center. Patients ≥12 years old with CT imaging ordered to evaluate for possible appendicitis were eligible. Participants underwent CT and MR imaging serially.

CT was performed using a 64-slice multi-detector CT (VCT, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) following oral contrast and intravenous iohexol (Omnipage-300, GE Healthcare, London, UK) administration in the portal venous phase. Size-specific protocols for small, medium, and large body habitus ranged from 100-140 kVp, noise index = 15-21, and Smart mA with mA range = 30-600. Images were reconstructed with 5mm slice thickness at 3mm intervals using a 40% ASIR blend in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes.

MRI was performed on 1.5T scanners (Signa HDxt CRM or TwinSpeed, Discovery MR450w) using an 8-channel body phased array coil and included non-contrast MR with diffusion-weighted imaging and contrast-enhanced MR. For contrast-enhanced T1w imaging, 0.1mmol/kg of gadobenate dimeglumine was administered at 2ml/s, followed by a 20ml saline flush. The MR protocol has been previously reported.4

Three fellowship-trained abdominal radiologists, blinded to the clinical CT read, interpreted all MR and CT images independently and in random order, using a standardized data collection form, which included the likelihood of appendicitis and the presence of an alternate diagnosis. Follow-up consisted of a chart review for pathological/surgical findings of patients who underwent laparotomy; all others had a follow-up phone interview with chart review. An expert panel of two radiologists and an emergency physician determined the diagnoses of all patients utilizing these follow-up data.

From the list of diagnoses generated by the expert panel, we selected patients who had an acute diagnosis identifiable on imaging. Next, we tabulated the number of instances that these diagnoses were correctly reported. Results are presented for each image type (non-contrast MR, contrast-enhanced MR, and CT) as interpreted by individual study radiologists as well as by consensus read (i.e. ≥2 radiologists identified the diagnosis). Data are reported as raw numbers and percentages.

Results

We enrolled 230 patients (2/2012-8/2014). Images from the first 20 patients were used as a training set for the study radiologists. Another 6 patients did not have complete MR images and were excluded, leaving 204 patients. Of these, 150 (73.5%) had an acute diagnosis identified by the expert panel, 113 (75%) of which could be identified on imaging.

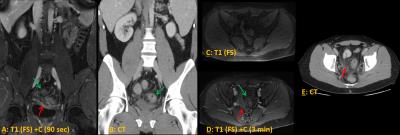

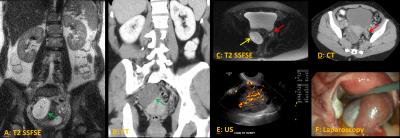

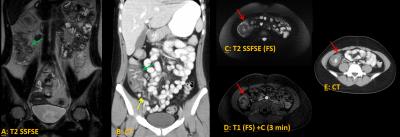

The overall accuracy of NC-MR, CE-MR, and CT was 77%, 83%, and 90% for individual reads and 82%, 84%, and 94% for consensus reads (Table). The accuracy CE-MR was superior to NC-MR in some diagnoses (e.g. – abscess, appendicitis, cholecystitis) when assessing individual radiologists, however was not as pronounced in the consensus interpretation. The accuracy of CT was better than MR in several diagnoses, particularly epiploic appendagitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis (Table). Imaging examples of diverticulitis, ovarian torsion, ureterolithiasis, and colitis are shown in figures 1-4.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the diagnostic accuracy of abdominal MR was frequently lower than CT to identify the etiology of abdominal pain for patients presenting to the ED. Like other authors,5,6 we previously reported the test accuracy of MR for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis,7 however, we now present the accuracy of diagnosing any etiology for abdominal pain. Since previous work investigating the use of CT has demonstrated that non-appendicitis pathologies have a higher incidence than appendicitis in those undergoing abdominal imaging, understanding the accuracy of MR as it pertains to alternative diagnoses is imperative. Limitations to our finding include the small sample sizes for some diagnoses (sometimes just a single case) as well as the fact that our study radiologists had primarily focused on the diagnosis of appendicitis, not any cause for abdominal pain.Acknowledgements

Research reported in this abstract was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under awards UL1 TR000427 and KL2 TR000428 as well as the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases under awards K24 DK102595 and K08 DK111234. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.References

1. Bhuiya F, Pitts S, McCaig L. Emergency Department Visits for Chest Pain and Abdominal Pain: United States, 1999-2008. National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db43.htm. Published September 2010. Accessed November 8, 2016.

2. HCUPnet: A tool for identifying, tracking, and analyzing national hospital statistics. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp?Id=1E1EE590A4752BF5&Form=DispTab&JS=Y&Action=Accept. Accessed August 17, 2015.

3. Pooler BD, Lawrence EM, Pickhardt PJ. Alternative diagnoses to suspected appendicitis at CT. Radiology. 2012;265(3):733-742. doi:10.1148/radiol.12120614.

4. Kinner S, Repplinger MD, Pickhardt PJ, Reeder SB. Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal MRI for Suspected Appendicitis: How We Do It. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(1):49-57. doi:10.2214/AJR.15.15948.

5. Leeuwenburgh MMN, Wiezer MJ, Wiarda BM, et al. Accuracy of MRI compared with ultrasound imaging and selective use of CT to discriminate simple from perforated appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101(1):e147-155. doi:10.1002/bjs.9350.

6. Cobben L, Groot I, Kingma L, Coerkamp E, Puylaert J, Blickman J. A simple MRI protocol in patients with clinically suspected appendicitis: results in 138 patients and effect on outcome of appendectomy. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(5):1175-1183. doi:10.1007/s00330-008-1270-9.

7. Repplinger MD, Pickhardt PJ, Kitchin DR, Robbins JB, Ziemlewicz TJ, Reeder SB. Direct Comparison of a Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol With Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography to Diagnose Appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(4):S21-S21.

Figures