4838

The direct and indirect findings of pulmonary embolism found on contrast enhanced pulmonary Magnetic Resonance Angiography exams: A pictorial essay approach for the imager based on the real world findings found in over 600 patients1Radiology, UW Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

The use of contrast enhanced pulmonary magnetic resonance angiography (CE-MRA) is being used as a primary modality for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) at our institution. We have found both direct and indirect findings of PE on CE-MRA images. It is of critical importance to have a thorough understanding of the pitfalls in the diagnosis of PE using this modality. This pictorial essay will help to educate imaging physicians about these pitfalls and the associated indirect findings that can point to the presence of this important disease.

Purpose

Teaching the clinical imaging physician the critical contrast enhanced pulmonary magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRA) signs for the diagnosis pulmonary embolism (PE) and their mimics.Outline of Content

Our group has been performing CE-MRA for the primary diagnosis of PE for the last eight years. (1,2) We have experience with at least 600 distinct clinical subjects and over 1,000 exams. This educational exhibit will highlight the direct and the indirect findings associated with PE. This presentation will contrast the CE-MRA findings with those typically found at contrast enhanced computed tomographic angiography (CTA).

Direct findings:

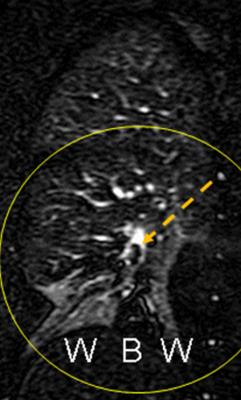

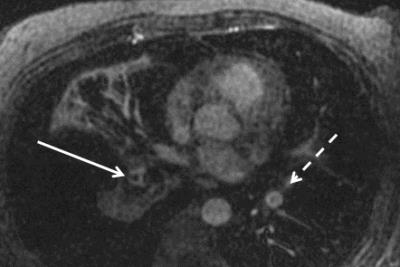

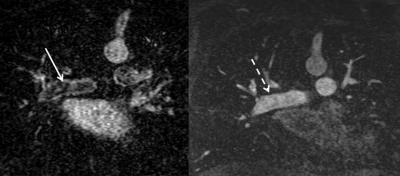

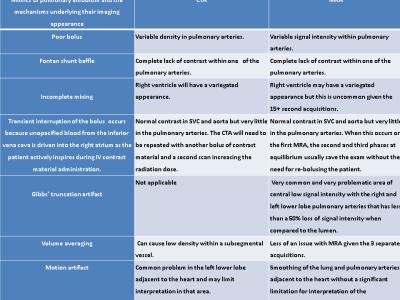

The most common finding in CE-MRA is observing a central filling defect within a pulmonary artery that is at least 50% lower in signal intensity than the surrounding contrast enhanced vessel lumen. The use of the double bronchus sign and vessel cutoff seen on the rotating MIPs can be helpful for the correct interpretation of an occlusive PE (Table 1, Figures 1-3). Sometimes one is able to find the high signal intensity clot on the precontrast MRA.

Indirect findings:

The presence of a pleural effusion and perfusion defects are also important for evaluation as these ancillary findings can help the imager find an occult embolus. Other indirect findings to look for include the following: pericardial effusion, white-black-white perfusion defect, enhancing parietal pleura, enhancing pleural effusions, right ventricle/left ventricle short axis ratio, and differential pulmonary venous signal intensity in those areas of the lung affected by nearly or completely occlusive PE (Table 2).

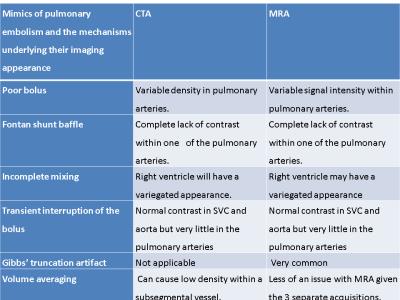

Mimics of PE:

First and foremost, an understanding the physics behind the formation of the very commonly seen Gibbs’ truncation artifact is needed, as this can appear to be a non-occlusive PE (Figure 1).(3) This can be distinguished from PE by knowing its location and finding its signal intensity relative to the surrounding lumen. Almost all PE will have a greater than 50% lower signal intensity than the luminal contrast surrounding it.(3) Transient interruption of the bolus can be found if the subject breaths in during the bolus phase,(4) this artifact is eliminated by the second and third CE-MRA acquisitions, which are performed in the equilibrium phase.(2)

Summary

This pictorially oriented exhibit for the imaging physician reviews the most common direct and indirect findings of PE found and CE-MRA. With careful attention to the mimics of this disorder a correct interpretation of these exams is easily performed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge research support from GE Healthcare.References

1. Schiebler ML, Nagle SK, Francois CJ, et al. Effectiveness of MR angiography for the primary diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes at 3 months and 1 year. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI 2013;38(4):914-925.

2. Nagle SK, Schiebler ML, Repplinger MD, et al. Contrast enhanced pulmonary magnetic resonance angiography for pulmonary embolism: Building a successful program. Eur J Radiol 2016;85(3):553-563.

3. Bannas P, Schiebler ML, Motosugi U, Francois CJ, Reeder SB, Nagle SK. Pulmonary MRA: differentiation of pulmonary embolism from truncation artefact. Eur Radiol 2014;24(8):1942-1949.

4. Wittram C. How I do it: CT pulmonary angiography. AJR AmericanJjournal of Roentgenology 2007;188(5):1255-1261.

Figures