4262

The Effects of Long-Term Physical Intervention for Active Ageing on the White Matter Hyperintensities in Older Adults1NeuroImaging & Informatics, National Center for Geriatrics & Gerontology, Ohbu, Japan, 2Department of Radiological Science, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan, 3Center for Comprehensive Care and Research on Memory Disorders, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Ohbu, Japan, 4Center for Comprehensive Care and Research on Memory Disorders, National Center for Geriatrics & Gerontology, Ohbu, Japan, 5College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Mie University, Tsu, Japan, 6Faculty of Human Sciences, Kobe Shoin Women's University, Kobe, Japan

Synopsis

The relationship between the history of participation in community based physical exercise activity and the volume of white matter hyperintensity was evaluated in order to investigate the long-term effects of physical exercises on the neurophysiological status of brain to support cognitive processing in older adults. The FLAIR MR images obtained from 54 community dwelling older adults were segmented semi-automatically and the WMH volumes were quantified. It was suggested that long-term physical exercises more than 5 years for 90 minutes once per week may potentially reduce the progress of WMH lesions as well as the risk of fall.

Introduction

The term “active ageing” represents a view that longer life must be accompanied by continuing opportunities for health, participation and security. Nowadays, many community-based programs to promote physical exercises (PE) for older adults have been widely organized, especially in Asian countries with rapid aging of the society. In those programs, the effects of PE on cognitive function have been the concern, since health promotion to delay cognitive impairments are essential as pre-medical care for sustainable aging society. Most of the neuroimaging studies to evaluate the outcomes of PE have focused on the cognitive performance after short to midterm interventions [1]. In this study, we evaluated the relationship between the history of PE and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) in order to investigate the long-term effects of PE on the neurophysiological status of brain to support cognitive processing in older adults. The morphological change of WMH reflects microangiopathy and demyelination [2]. Since WMH is a long-term and irreversible change of the tissue for neuronal connections, we hypothesize that WMH may be a stable biomarker to evaluate the cumulative effects of PE.Materials and Methods

Fifty-four healthy community dwelling older adults (Age 63–78, average 69.9, 36 females), who gave written informed consent approved by the IRB, participated in this study. Their histories of participation in the physical exercise club (PEC) for older adults and fall [6] were interviewed. Magnetic resonance (MR) images were obtained by using a T2 (TR 5920ms, TE 95ms, 3mm thick, 0.75mm gap, 39 slices, FOV 192mm, matrix 256x256) and a FLAIR (TR 9000ms, TE 102ms, Ti 2600ms, 3mm thick, 0.75mm gap, 39 slices, FOV 192mm, matrix 256x256, NEX 2) sequences on a 3T MRI scanner. The volumes of WMH were quantified by using SNIPER (LUMC, Leiden). Segmentation of the WMH was manually corrected after automatic processing [3]. Association between WMH volumes and the scores of physical or cognitive functions was tested by a partial correlation analysis (age and sex adjusted). The effect of the period of PE on these variables was evaluated by an analysis of variance (p<0.05).Results

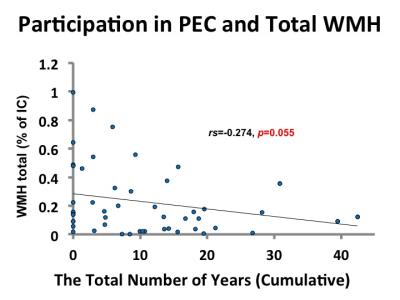

Among the 54 subjects, 40 participated (32 females) in the PEC. None of the subjects recorded MMSE score less than 26. The exercise protocol was 90 minutes per day and once a week throughout a year. The relationship between the PEC and episode of fall within last one year are is shown in Fig.1 (ANCOVA, p < 0.05, age corrected). Among the obtained scores for each psychological test and survey, the followings were confirmed in this subject group: 1) The episode of fall correlated with the changes of brain volume (increase of CSF space and decrease of total and regional parenchymal volumes of the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes, p<0.05). 2) The subjects participating in PEC for more than 5 years reported less episode of fall, while the fall risk index [4] was higher in the participants of PEC (p<0.05). 3) Participation in PEC positively correlated with less volume of WMH in temporal and parietal region and CSF volume (p < 0.05). The correlation with total volume of WMH was less (Fig.2). 4) Less WMH volume was extracted in the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes as well as in the deep white matter region in the participants of PEC (p<0.05). 5) The correlation between the volume of WMH lesions and age was not significant.Discussion

Frequencies of WMH without dementia range from 11–20% of middle-aged people to 100% at age 85 [5], and WMH lesions are related with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular risk factors. Progression of WMH suggests fall risk [6] and PE reduce fall risk [7, 8]. In this study, the effect of long-term PE (over 5 years) to prevent fall was demonstrated, although FRI was higher in the participants of PEC, suggesting that they are more sensitive to and aware of the risk of fall. It was also shown that brain volume loss and appearance of WMH was less in the participants of PEC. Of note was that subjects almost without WMH were observed up to 75 years old in this subject group and it is quite different distribution from previous studies [9], suggesting that long-term PE may be a strong suppressor of WMH. The results of this study suggested that such effects in long term appear as morphological changes of brain. In conclusion, it was suggested that long-term PE more than 5 years for 90 minutes once per week may preserve white matter and it may potentially reduce the progress of WMH lesions.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) #15H03104 supported by MEXT.References

[1] Ratey JJ, Loehr JE. Rev Neurosci 22, 171-8, 2011 [2] S. Debette and H. S. Markus, BMJ 341, #3666, 1-9, 2010 [3] Ogama N, Yoshida M, Nakai T et al., Geriat Gerontol Int 16, 167-74, 2016}|[4] Toba K, Japan Medical Association Journal 52, 237-242, 2009[5] E. Garde, E. L. Mortensen, K. Krabbe, E. Rostrup, and H. B. Larsson, Lancet 356, 628 - 34, 2000.[6] Callisaya ML, Beare R, Phan T et al., J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70, 360-6, 2015[7] El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Charles MA, Dargent-Molina P, BMJ 29, #347, 1 - 13, 2013[8] Arnold CM, Sran MM, Harrison EL, Physiother Can 60, 358 - 72, 2008[9] Ikram AM, Vrooman AH, Vernooij WM et al., Neurobiology of Aging 29, 882–890, 2008

Figures

Figure 1

The relationship between the history of PEC (years) and the episode of fall during the last one year. The fall episode was frequent in the subgroup with participation for 5 years and under compared with the sum of other three subgroups (p < 0.05).

Figure 2

The relationship between the history of PEC (years) and the total amount of WMH volume. The correlation was higher in the subregions (see text).