3250

Exenatide decreases ectopic fat accumulation but have no impact on myocardial function and perfusion in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes1Aix-Marseille University, CRMBM, NORT, Marseille, France, 2Aix-Marseille University, NORT, AP-HM, 3Aix-Marseille University, CRMBM, AP-HM, 4Aix-Marseille University, CRMBM, 5Aix-Marseille University, NORT, 6University of Oxford, OCMR

Synopsis

The objective of the study is to assess the impact of Exenatide on endothelial reactivity, and change in ectopic fat and cardiac function. This study included 44 patients (mean 52 years) randomized to Exenatide or reference treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging was used to assess ectopic fat accumulation, coronary vasoreactivity and cardiac function. 16-weeks of Exenatide treatement resulted in a significant improvement in glycemic control and a significant reduction of both epicardial fat and hepatic steatosis. However, we found no effect of Exenatide on myocardial function. In addition, one-week of exenatide treatment had only a modest effect on vascular reactivity, albeit non-significant.

Introduction

GLP-1 receptor agonists have been postulated as a promising treatment for ectopic fat and cardiovascular protection because of their beneficial effects on body weight, glycemic control, and inflammation. Furthermore, the LEADER study demonstrated significant reduction of cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetes patients treated with liraglutide treatment for 3.5 years1. The impact of ectopic fat deposition on cardiovascular system has been widely described. In particular, epicardial fat has been shown to be an independent predictor of coronary events2. In addition to epicardial fat increase, ectopic fat depots in the myocardium, liver and pancreas are also significantly increased in T2D3,4. In our previous pre-clinical study, we demonstrated significant reduction of ectopic fat deposition associated with cardiac function and perfusion improvements in obese and type 2 diabetes mice treated with Exenatide5. This study is a prospective randomized placebo-controlled trial aimed at confirming our pre-clinical results in humans. Accordingly, we investigated the short-term (7days) effect of exenatide on endothelial reactivity, as well as long-term effect (16weeks) on ectopic fat stores and cardiac function.Patients and methods

This study has been performed on 44 type 2-diabetes patients randomized to either exenatide or reference treatment, as defined by treatment intensification according to local guidelines. Coronary microcirculation reactivity was assessed one-week after treatment using accurate MRI method already validated on healthy volunteers3,6. Velocity encoded phase contrast cine-CMR (VEC-CMR) technique was performed to quantify coronary sinus flow. This technique was combined to a cold pressure test in order to assess endothelium-dependent, coronary reactivity in response to sympathetic stimulation. Triglyceride accumulation in the heart and the liver has been quantified by proton spectroscopy using PRESS sequence, as previously described4. Cine breath-hold balanced Steady-State-Free-Precession (bSSFP) cine sequences were used to quantify epicardial adipose tissue and cardiac function. Epicardial adipose tissue was manually delineated in all SAX images. Surfaces were then summed and multiplied by slice thickness to obtain epicardial adipose tissue volume. Global cardiac function was assessed using Argus software (Siemens) and strain analysis was performed using commercially available software (cmr42, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc, Calagary, Canada).Results

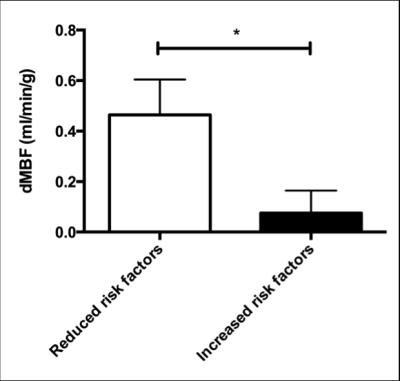

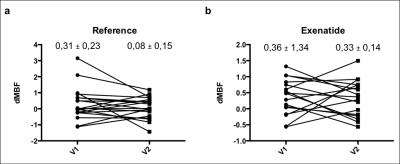

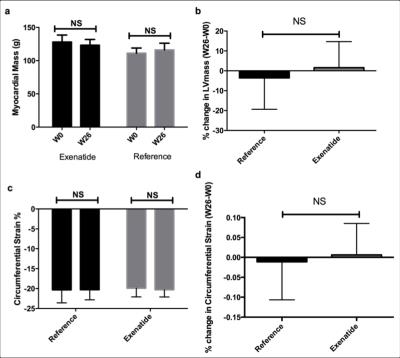

Mean age of this population was 52±1 years, and BMI was 36.1±1.1kg/m2. There is no significant difference between groups in baseline characteristics. Cold pressure test (CPT) induced a significant increase in heart rate (+9,3%) similar in both groups, together with myocardial blood flow increase from 1,63±0,12 vs 1,96±0,16 mL/g/min (p=0,02). Myocardial blood flow response to CPT (dMBF) was not influenced by BMI, or by epicardial fat in contrast to healthy volunteers’ previous study3. Nevertheless, patients with high cardiovascular risk factors including age, hypertension, smoking, HDL-cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, and microalbuminurea have significantly reduced dMBF compared to the remaining patients with 0,08±0,09 vs. 0,46±0,14 mL/g/min respectively; p=0,03 figure 1. One-week treatment induced a significant improvement in glycemic control, in reference and exenatide group. Furthermore, we observed different coronary sinus response between groups in the second visit (V2) 0,08±0,15 vs 0,33±0,14; p=NS, although it was non significant; while this response was perfectly similar between groups at the first visit (V1) 0,31±0,23 vs 0,36±1,34; p=NS figure 2. Exenatide induced a significant weight loss compared with reference treatment (−5.3 ± 1.0% vs −0.2 ± 0.8%; p = 0.0004), whereas there was a similar improvement in HbA1c in each group (−0.7 ± 0.3 vs. −0.7 ± 0.4%; p = 0.29) This weight loss was also associated with significant reduction in EAT (−8.8 ± 2.1%) compared with the reference treatment (−1.2 ± 1.6%; p = 0.003), and important reduction in liver fat content was observed in the exenatide group compared to the reference group (−23.8 ± 9.5% vs. +12.5 ± 9.6%, p = 0.007). By contrast, no significant change was observed for myocardial steatosis and pancreatic steatosis (These data on ectopic fat have been already published)7. Finally, exenatide treatment did not have impact on myocardial function after 26 weeks (V4); neither on systolic and diastolic global cardiac function, nor in the regional contractility (p=NS). 26-weeks exenatide treatment did even not change LV mass figure 3.Conclusion

This randomized controlled study was designed in order to assess the effect of exenatide treatment on endothelial function, ectopic fat change, and cardiac function. Exanatide over one week did not result in improved vasoreactivity one week after treatment, compared to control, suggesting that GLP-1 mediated cardioprotection does not act through improved endothelial function. In contrast, epicardial fat and liver steatosis are significantly reduced and this provides a new insight into the beneficial effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Myocardial systolic and diastolic function and myocardial steatosis were all not changed after 26 weeks of GLP-1 treatment.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, Nissen SE, Pocock S, Poulter NR, Ravn LS, Steinberg WM, Stockner M, Zinman B, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB; LEADER Steering Committee.; LEADER Trial Investigators. « Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. » N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 28;375(4):311-22.

2- Mahabadi AA, Berg MH, Lehmann N, Kälsch H, Bauer M, Kara K, Dragano N, Moebus S, Jöckel KH, Erbel R, Möhlenkamp S. « Association of epicardial fat with cardiovascular risk factors and incident myocardialinfarction in the general population: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study ». J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Apr 2;61(13):1388-95.

3- Gaborit B, Kober F, Jacquier A, Moro PJ, Flavian A, Quilici J, Cuisset T, Simeoni U, Cozzone P, Alessi MC, Clément K, Bernard M, Dutour A. « Epicardial fat volume is associated with coronary microvascular response in healthy subjects: a pilot study. » Obesity 2012 Jun;20(6):1200-5.

4- Gaborit B, Abdesselam I, Kober F, Jacquier A, Ronsin O, Emungania O, Lesavre N, Alessi MC, Martin JC, Bernard M, Dutour A. « Ectopic fat storage in the pancreas using 1H-MRS: importance of diabetic status and modulation with bariatric surgery-induced weight loss. » Int J Obes. 2015 Mar;39(3):480-7.

5- Abdesselam I, Pepino P, Troalen T, Macia M, Ancel P, Masi B, Fourny N, Gaborit B, Giannesini B, Kober F, Dutour A, Bernard M. « Time course of cardiometabolic alterations in a high fat high sucrose diet mice model and improvement after GLP-1 analog treatment using multimodal cardiovascular magnetic resonance. » J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015 Nov 6;17:95.

6- Moro PJ, Flavian A, Jacquier A, Kober F, Quilici J, Gaborit B, Bonnet JL, Moulin G, Cozzone PJ, Bernard M. « Gender differences in response to cold pressor test assessed with velocity-encoded cardiovascular magnetic resonance of the coronary sinus. » J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011 Sep 23;13:54.

Figures