2373

The relationship between brain white matter hyperintensities burden and age-related neuropathologies is location dependent1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, United States, 2Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, United States, 3Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, United States, 4Department of Pathology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, United States, 5Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, United States

Synopsis

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are white matter lesions appearing hyperintense in T2-weighted MRI. WMH are common in older adults and have been associated with increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Previous efforts have attempted to identify the neuropathologies associated with whole brain WMH burden. However, it is yet to be determined if the relationship between regional WMH burden and age-related neuropathologies is the same, or varies, in different parts of the brain. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to investigate the association between regional WMH burden and neuropathologies in a community cohort of older adults.

Purpose

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are white matter lesions appearing hyperintense in T2-weighted MRI. WMH are common in older adults and have been associated with increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia1-4. Previous efforts have attempted to identify the neuropathologies associated with whole brain WMH burden5-7. However, it is yet to be determined if the relationship between regional WMH burden and age-related neuropathologies is the same, or varies, in different parts of the brain. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to investigate the association between regional WMH burden and neuropathologies, by combining ex-vivo brain MRI and histology in a community cohort of older adults.Methods

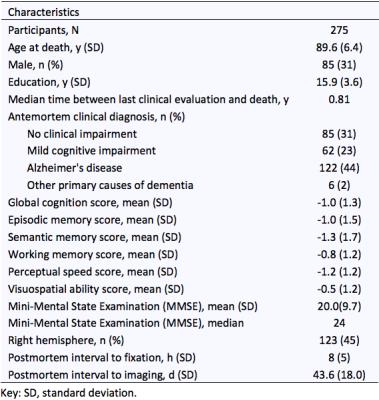

Cerebral hemispheres were obtained from 275 participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project8 and Religious Orders Study9, two longitudinal, epidemiologic clinical-pathologic cohort studies of aging (Fig.1). All hemispheres were imaged ex-vivo on a 3T clinical MRI scanner, while immersed in 4% formaldehyde solution, using a 2D spin-echo sequence with multiple echo-times and a FLAIR sequence. An experienced observer blinded to all pathologic and clinical data manually outlined WMH on multi-echo spin-echo images from TE = 50 msec, using FLAIR images for guidance. The white matter of each hemisphere was segmented into periventricular and deep white matter using an automated approach that classified voxels located within 5-6mm from the edges of the ventricles (depending on hemisphere size) as periventricular. Both periventricular and deep white matter segments were then further divided into frontal, temporal, and parieto-occipital regions through registration to a brain atlas including the corresponding labels. The total volume of WMH in each of the six white matter segments was measured for each hemisphere. Regional WMH burden was defined as the square root of the regional WMH volume normalized by the height of the participant.

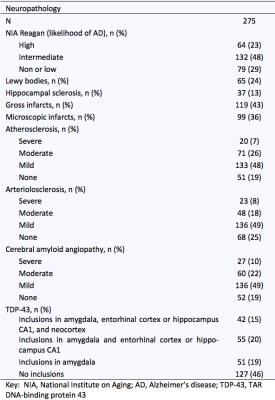

Neuropathologic assessment was performed by a board-certified neuropathologist blinded to all clinical and imaging findings (Fig.2). The pathologies that were considered in analyses were: amyloid plaques, PHFtau tangles, Lewy bodies, TDP43, hippocampal sclerosis, gross infarcts, microscopic infarcts, atherosclerosis, arteriolar sclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).

Multiple linear regression was used in each white matter segment (frontal, temporal and parieto-occipital periventricular and deep white matter) to investigate the link between regional WMH burden and age-related neuropathologies, controlling for age at death, sex, education, and postmortem interval to fixation.

Results and Discussion

Arteriolosclerosis was associated with WMH burden in most white matter segments [in parieto-occipital periventricular white matter (0.93, p=0.012), and in all three deep white matter segments, frontal: (5.02, p=0.003); temporal: (2.00, p=0.040); parieto-occipital: (1.79, p=0.046)]. Arteriolosclerosis has been previously linked to whole brain WMH burden5,6. Gross infarcts were associated with WMH burden in frontal periventricular (0.86, p=0.051) and deep white matter (4.51, p=0.018). Infarcts have been previously linked to WMH burden in frontal deep white matter7. Atherosclerosis was associated with WMH burden in frontal periventricular (2.10, p=0.012) and deep white matter (5.47, p=0.003). CAA was associated with WMH burden in parieto-occipital deep white matter (1.9, p=0.017). CAA has previously been shown to be more severe in the occipital lobe10. Tangles were associated with WMH burden in frontal periventricular white matter (1.99, p=0.039) and temporal deep white matter (2.66, p=0.029). Tangles are known to accumulate in temporal as well as frontal lobes11.Conclusion

The present study in a large community cohort demonstrated for the first time that the relationship between WMH burden and age-related neuropathologies is location dependent. Although arteriolosclerosis is linked to WMH burden in most of the brain, gross infarcts and atherosclerosis are linked to WMH in the frontal lobe, CAA is linked to WMH burden in occipital and parietal brain regions, and tangles are associated with WMH burden in frontal and temporal lobes. Also, CAA was only linked to WMH burden in deep white matter, while all other pathologies with significant associations were linked to WMH burden in both periventricular and deep WMH. The differences in the spatial patterns of WMH associated with different age-related neuropathologies may aid in diagnosis, and therefore the findings of the present work may be of high significance.Acknowledgements

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) UH2NS100599

National Institute on Aging (NIA) R01AG017917

National Institute on Aging (NIA) P30AG010161

National Institute on Aging (NIA) R01AG034374

References

1. The LADIS study group, Poggesi A, Pantoni L, et al. 2001-2011: A Decade of the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis And DISability) Study: What Have We Learned about White Matter Changes and Small-Vessel Disease? Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;32:577-588.

2. Silbert LC, Nelson C, Howieson DB, et al. Impact of white matter hyperintensity volume progression on rate of cognitive and motor decline. Neurology 2008;71:108-113.

3. Arvanitakis Z, Fleischman DA, Arfanakis K, et al. Association of white matter hyperintensities and gray matter volume with cognition in older individuals without cognitive impairment. Brain Struct Funct 2016;221:2135-2146.

4. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3666.

5. Erten-Lyons D, Dodge HH, Woltjer R, et al. Neuropathologic basis of age-associated brain atrophy. Neurology 2013;70:616-622.

6. Shim YS, Yang DW, Roe CM, et al. Pathological correlates of white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2015;39:92-104.

7. Polvikoski TM, van Straaten EC, Barkhof F, et al. Frontal lobe white matter hyperintensities and neurofibrillary pathology in the oldest old. Neurology 2010;75:2071-2078.

8. Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, et al. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:646–663.

9. Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Arvanitakis Z, et al. Selected findings from the Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis 2013;33 Suppl 1:S397-403.

10. Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Wang Z, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy pathology and cognitive domains in older persons. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:320-327.

11. Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging 1997;18:351-357.